Islamic Spirituality and Mental Well-Being

Introduction

The Role of Spirituality in Emotional and Mental Well-Being

When you think very deeply about all the affairs [of this world], you will be at a loss. Your contemplation will inevitably lead to the understanding that everything in this worldly life is temporary. Thus, one must recognize that true purpose lies in only working for the hereafter [which is eternal]. This is because at the end of all your dreams and aspirations in this world is the eventuality of ḥuzn [grief] – Either your ambitions are taken away from you, or you are forced to give up your goals [both pathways will lead to grief]. There is no escape from these two ends except in striving towards God. In this case, a person achieves happiness in this life and for eternity. Their hamm is a lot less compared to the hamm of humankind. They are respected by friend and foe alike and, as for their eternity, then it is paradise.[15]

Spiritual intelligence and the ability to process life events

He said, ‘I do not think this will ever end. And I do not think that the hour will be established, and even if I am returned to My Lord then I will find in with Him an even better placing.’[17]

And why didn’t you say when you entered your garden, ‘[This is] What God Wills and there is no capability except through God.’[18]

The past can never be changed or corrected with sadness [ḥuzn], but rather with contentment [riḍā], gratitude [ḥamd], patience [ṣabr], a firm belief in destiny [imān bil qadar] and the verbal recognition that everything occurs by the Decree of God [qaddarAllāhu wa mā shā wa fa’l].[22]

A Psycho-spiritual Analysis of a Prophetically Prescribed Prayer for Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

Whoever is afflicted with grief or anxiety, then he should pray with these words, ‘Oh Allāh, certainly I am your slave, the son of your male slave and the son of your female slave. My forehead is in Your Hand. Your Judgment upon me is assured and Your Decree concerning me is just. I ask You by every Name that you have named Yourself with, revealed in Your Book, taught any one of Your creation or kept unto Yourself in the knowledge of the unseen that is with You, to make the Qurān the spring of my heart, and the light of my chest, the banisher of my sadness and the reliever of my distress.’[28]

The second category of diseases of the heart are based on emotional states such as anxiety, sadness, depression, and anger. This type of disease can be treated naturally by treating the cause or with medicine that goes against the cause…And this is because the heart is harmed by what harms the body and vice versa.[29]

Du’aā as Psychotherapy

Analysis

1 – Oh Allāh, certainly I am your slave, the son of your male slave and the son of your female slave.

Know that the life of this world is but amusement, diversion, adornment, boasting to one another and competition in increase of wealth and children. The example of this is like a rain that results in plant growth, immediately pleasing the farmers. Then it inevitably turns yellow and then becomes scattered debris…[34]

Beautifying one’s appearance would seem to be a healthy expression of freedom, until of course, we witness the alarming devaluation of the self that has become rampant in the modern cosmetic culture…The striking proportion of society willing to go under the knife to change themselves may represent physical freedom to some, but it may also suggest a worrying degree of psychological enslavement.[35]

What we are supposed to want and desire is programmed and conditioned into our thoughts by a cultural and marketing tsunami that engulfs our minds right from childhood.[36]

Psychological slavery also manifests in an obsession with entertainment, illusion and fantasy. Two decades ago, one author noted that the average American child watched more television by the age of 6, than the amount of time one speaks to one’s father in an entire lifetime.[37]

And in this [statement] is the perfection of submission, humility, and gnosis through [the expression of] servitude to God. This is because it was not simply stated ‘I am your servant,’ but it was further emphasized through ‘son of your male servant and son of your female servant.’ This indicates a hyperbolic emphasis on submission and servitude to God. This is because the solitary servant is not the same as a servant, whose father is also a servant.[42]

Ḥudhayfah said, “When the Prophet ﷺ would be in an overwhelming situation, he would pray ṣalah.”[45]

2 – My forehead is in Your Hand. Your Judgment upon me is assured and Your Decree concerning me is just.

Ṣuhayb reported: The Prophet ﷺ, said, “Wondrous is the affair of the believer as there is good for him in every matter, and this is not true for anyone but the believer. If he is pleased, then he thanks Allāh and there is good for him. If he is harmed, then he shows patience and there is good for him.”[47]

3 – I ask You by every Name that you have named Yourself with, revealed in Your Book, taught any one of Your creation or kept unto Yourself in the knowledge of the unseen that is with You.

4 – To make the Qurān the spring of my heart, the light of my chest, the banisher of my sadness and the reliever of my distress.

And We have sent down to you the Book as clarification for all things and as guidance and mercy and good tidings for the Muslims.[56]

A book which We have revealed to you so that you might bring humankind out of darkness into the light by the permission of their Lord to the path of the Exalted in Might, the Praiseworthy.[57]

Conclusion

Notes

[1] Positive Psychology represents a movement within psychology recognizing the need to move beyond abnormal psychology (mental illness). It focuses on strengths and virtues rather than disorders and pathology. It was founded by Martin Seligman, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Christopher Peterson in the year 2000.

[2] Snyder C., Lopez S. J., & Pedrotti, J. T. (2010). Positive psychology: The scientific and practical explorations of human strengths. Sage Publications. 2nd Edition.

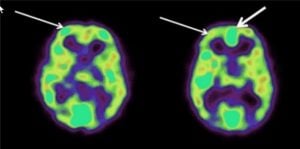

[3] Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2010). A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychological Medicine, 40(8), 1239-1252.

[4] Ibn Ḥazm. Akhlāq wa as-Sīr, p. 76.

[5] Smith, E.E. The power of meaning, p. 22.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Oishi, S., & Diener E. (2013). Residents of poor nations have a greater sense of meaning in life than residents of wealthy nations. Psychological Science, 25, 422-430.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Emmons, R.A. (2000). Is spirituality an intelligence? Motivation, cognition, and the psychology of ultimate concern. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 10(1), 3-26.

[15] Ibn Ḥazm. Akhlāq wa as-Sīr, p. 75.

[16] Emmons, op cit., pp. 3-26.

[17] Qurān, 18:35.

[18] Ibid, 18:39.

[19] McKee, D.D., & Chappel, J.N. (1992). Spirituality and medical practice. Journal of Family Practice, 35, 201-205.

[20] Guyatt, G. H., Mills, E. J., & Elbourne, D. (2008). In the era of systematic reviews, does the size of an individual trial still matter? PLoS Med, 5(1): e4.

[21] Wong, Y. J., Rew, L., & Slaikeu, K. D. (2006). A systematic review of recent research on adolescent religiosity/spirituality and mental health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 161-183.

[22] Ibn al-Qayyim, Zād al-M’aād, vol 2. p. 325.

[23] Baumeister, R.F., & Vohs, K.D. (2007). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 115-128.

[24] Ibn al-Qayyim, Iddat as-Sabireen wa Dakheerat ash-Shakireen, p. 35.

[25] Ibid, p. 49.

[26] Strauman, T. J. (2002). Self-regulation and depression. Self and Identity, 1(2), 151-157.

[27] Watkins, P.C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 31(5), 431-451.

[28] Musnad Imām Aḥmad #3712. Shu’ayb al-Arnaūt (d. 1437 AH) declared its chain of authorities (isnād) to be authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) in his publishing (taḥqeeq) of the Musnad.

[29] Ibn al-Qayyim, Ighāthat ul-Laḥfaan fī Maṣāyid ash-Shayṭān, p. 26.

[30] Porto, P.R., Oliveira L., Mari J., Volchan E., Figueira I., Ventura P. (2009). Does cognitive behavioral therapy change the brain? A systematic review of neuroimaging in anxiety disorders. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience, 21, 114-125.

[31] Qurān, 21:83.

[33] Snyder, M. (1974). Self-monitoring of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30, 526-537.

[34] Qurān, 57:20

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Newberg, A. B., Wintering, N. A., Yaden, D. B., Waldman, M. R., Reddin, J., & Alavi, A. (2015). A case series study of the neurophysiological effects of altered states of mind during intense Islamic prayer. Journal of Physiology – Paris, 109, 214-220.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Dietrich, A. (2006). Transient hypofrontality as a mechanism for the psychological effects of exercise. Psychiatry Research, 145, 79-83.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Badr ad-Deen Al-‘Ayni, Al-‘Ilm al-Hayyib fī Sharḥ al-Kalima at-Ṭayyib, p. 343.

[43] Newberg, et al.. (2015).

[44] Haruno, M., Kuroda, T., Doya, K., Toyama, K., Kimura, M., Samejima, K., Imāmizu, H., Kawato, M. (2004). A neural correlate of reward-based behavioral learning in caudate nucleus: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of a stochastic decision task. Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 1660-1665.

[45] Sunan Abī Dawūd #1319. Ibn Ḥajr al-Asqalānī (d. 852 AH) declared its authenticity as good (Ḥasan) (Takhrīj Mishkāt al-Maṣābīḥ vol. 2, p. 77).

[46] Badr ad-Deen Al-‘Ayni, Al-Ilm al-Hayyib fī Sharḥ al-Kalima at-Ṭayyib, p. 343.

[47] Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim #2999.

[48] Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

[49] Qurān, 21:88.

[50] Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī #4563.

[51] Qurān, 7:23.

[52] Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., & Sigmon, S. T. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 570-585.

[53] Eliott, J. A. (2005). Interdisciplinary perspectives on hope. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

[54] Ibn al-Qayyim, Madārij as-Sālikīn, vol. 1, p. 517.

[55] Haidt, J., & Keltner, D. (2003). Approaching awe: A moral, spiritual and aesthetic emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 17, 297-314.

[56] Qurān, 16:89.

[57] Ibid, 14:1.