Allah the Exalted says in Surat Ibrahim: “Art thou not aware how God sets forth the parable of a good word? [It is] like a good tree, firmly rooted, with its branches towards the sky, yielding its fruit at all times by its Sustainer's leave. And [thus it is that] God propounds parables unto men so that they might bethink themselves [of the truth].”

[8] The good word is the message of the faith; it is the glad tiding, the promise to believers of Allah’s pleasure.

The good word is a life of faith itself. The believer herself is like a good tree, whose roots are firmly planted—in Allah and His Messenger (peace be upon him)—and whose good speech and good actions, good intentions and good works, good knowledge and good manners, emanate throughout family and society—branches spreading wide and reaching for the sky. After the essential element of ritual worship, good works are the extra deeds by which a servant draws near to Allah and receives Allah’s love. As relayed in the prophetic saying:

On the authority of Abu Hurayrah (may Allah be pleased with him), who said that the Messenger of Allah, may Allah’s peace and blessings be upon him, said: “Allah (the Exalted) said: Whosoever shows enmity to someone devoted to Me, I shall be at war with him. My servant draws not near to Me with anything more loved by Me than the religious duties I have enjoined upon him, and My servant continues to draw near to Me with supererogatory works so that I shall love him. When I love him I am his hearing with which he hears, his seeing with which he sees, his hand with which he strikes and his foot with which he walks. Were he to ask [something] of Me, I would surely give it to him, and were he to ask Me for refuge, I would surely grant him it. I do not hesitate about anything as much as I hesitate about [seizing] the soul of My faithful servant: he hates death and I hate hurting him.”[9]

Our actions are the outer, visible portion of our tree of life: its branches and sweet, nourishing fruits. And our faith is what grounds us (gives us roots), providing our sustenance and determining our health and strength. Actions stem from faith. Belief determines and guides practice.

As the verses from Surat Ibrahim show, the good word, like a good tree, is firmly rooted with branches reaching the sky and yielding fruit all year long by Allah’s permission. However, just as good belief leads to good practice, so too does corrupt belief lead to corrupt practice. In the very next verse, Allah the Exalted says: “And the parable of a corrupt word is that of a corrupt tree, torn up [from its roots] onto the face of the earth, wholly unable to endure.”

[10] What lesson can these three verses from Surat Ibrahim teach us as we navigate culture in increasingly ungodly environs?

What is culture?

All human societies produce and enjoy distinct cultures. If we think of a culture as a tree, it is identifiable by its outermost manifestations—its customs, mores, aesthetics, and products. These are the habits, traditions, values, beauty standards, and sciences and arts of every type, including agriculture, animal husbandry, economy, politics, education, family life, cuisine, dress, music, dance, theatre, literature, poetry, etc. For Plato, artwork being mimetic, or imitative, of real-life objects, occupied a lower metaphysical stratum of life. The objects imitated are themselves lower than the ultimate realities, or

forms, they depict. Forms can only be grasped through contemplation, and artworks pertaining to the lower soul, ought to be subjected to moral realities. Art, for Plato, was not the default realm of beauty.

[11] Just like a tree, the outermost artistic extensions of a culture represent its firmness and health—in this case, its values. What are a society’s highest-ranking values? They will be reflected in the culture that is produced. And these cultural products and values are further rooted in and guided by the philosophy of that civilization (the tree’s roots). A society’s philosophy answers the most basic and universal human questions, including: What is life? What is the human being’s purpose? What ought we to aim at? What are the most important values that will help us achieve that aim? In this paper, I focus on factors and values to consider for American Muslim artistic cultural production within the broader American cultural arts.

Because a tree from root to fruit is a single organism, examining and tasting the culture reveals a great deal about the nature and foundations of that philosophical ground, and guides us to understand what nourishment—or harm, as the case may be—that culture is providing.

While “culture” is a modern behavioral concept,

[12] classical Islamic jurists spoke about

‘urf and

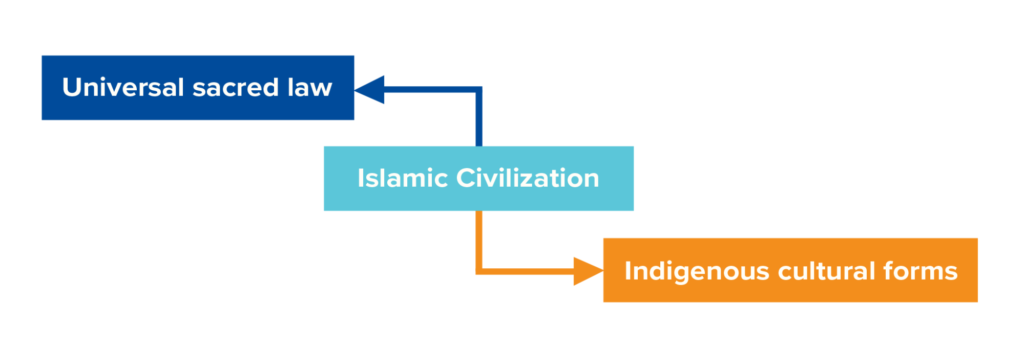

‘aada: custom and usage. Dr. ‘Umar Faruq ‘Abd-Allah in “Islam and the Cultural Imperative” argues that Islamic civilization—a civilization that spanned from China to the Indian subcontinent, Somalia, Senegambia, Italy, Spain, and as historical evidence suggests, reached the Americas centuries prior to Columbus

[13]—traditionally related to its sprawling variety of cultures in a distinctly healthy and productive way.

[14]‘Abd-Allah states: “In history, Islam showed itself to be culturally friendly and, in that regard, has been likened to a crystal clear river. Its waters (Islam) are pure, sweet, and life-giving but—having no color of their own—reflect the bedrock (indigenous culture) over which they flow. In China, Islam looked Chinese; in Mali, it looked African.”

[15] Culture for Muslims has always been understood as second nature. As such, Islamic law has always been known to implicitly endorse local cultures in their positive aspects.

‘Urf as a legal category indicates that cultural forms have the weight of law: if it is

sound culture that is neither prohibited nor explicitly harmful, then it enjoys the weight of law. The jurists were careful not to abuse or criminalize the sound aspects of local culture, for “to reject sound custom and usage was not only counterproductive, it brought…difficulty and…harm to people.”

[16] And this is because what people generally consider proper “tends to be compatible with their nature and environment, serving essential needs and valid aspirations.”

[17]Indeed it is from the sunnah of our Prophet, may God’s peace and blessings be upon him, to acknowledge the emotional needs, tastes, and cultural inclinations of all who embrace his teachings. Islam as a civilization, historically, was the perfect balancing point between the universal sacred law (the crystal clear river) and the indigenous cultural forms of a people (the distinctive and colorful bedrock over which that river flows).

Culture is so powerful it not only represents the underlying foundations of a people, but it can also

change those underlying foundations over time. Culture “governs everything about us and even molds our instinctive actions and natural inclinations.”

[18] The roots determine the outer manifestation, but the environment outside can also affect the deeper values. Our instincts, inclinations, desires, and values can be molded and influenced over time by actions and opinions that are culturally normative and prevalent.

Perhaps most importantly for developing responsible practice vis-à-vis culture today, we must understand the ways in which culture is rooted in expression, language, and symbol.

[19]Popular culture today

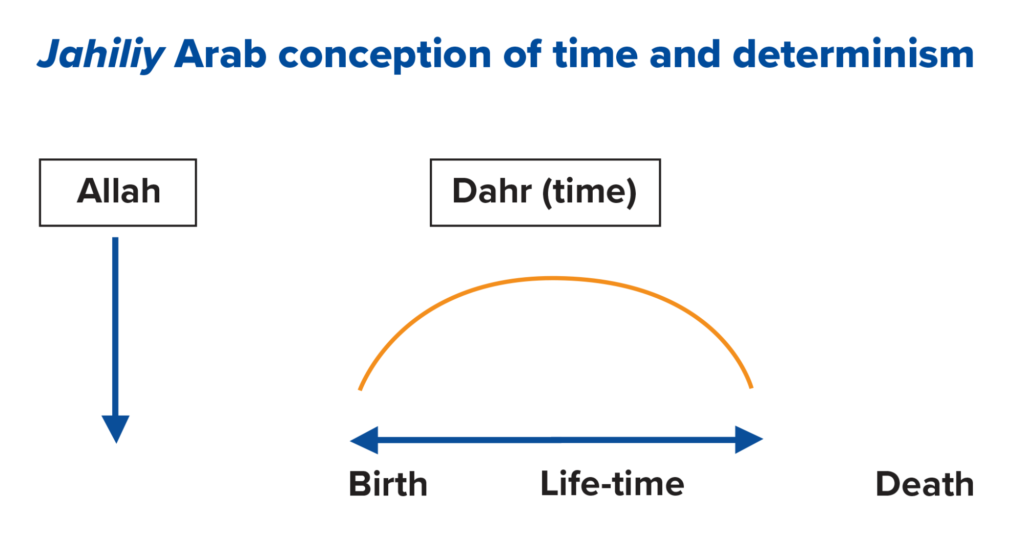

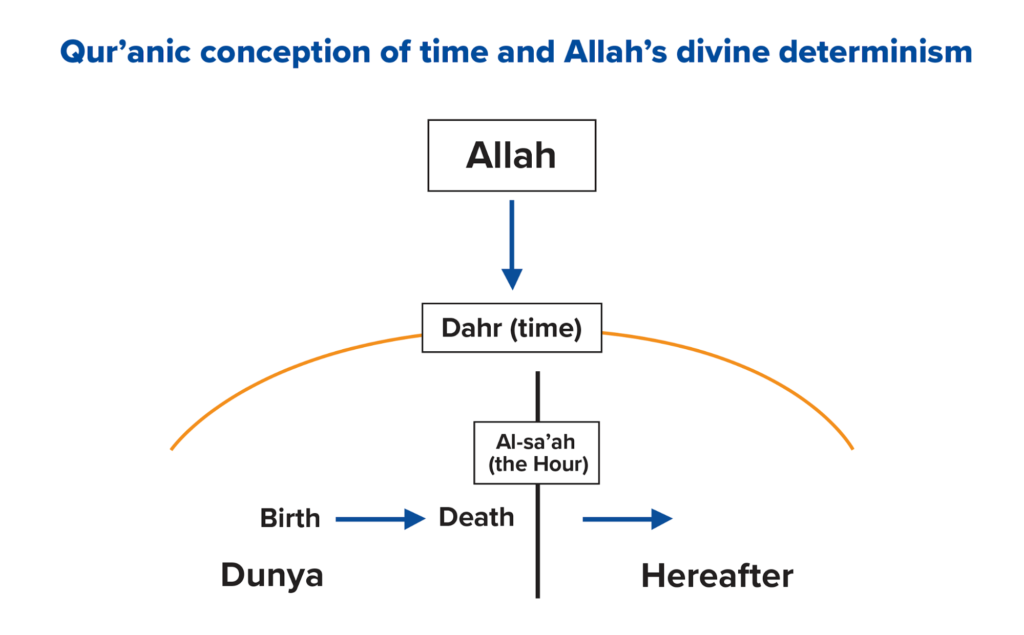

If culture is rooted in expression, language, and symbol, what do the expressions, language, and symbols of popular culture today reveal about our deeper values? Examining today’s American cultural production, it becomes apparent that the media of choice—the language and expressions most performed and consumed—include videos, poetry (found in song lyrics), movies, television series, and normative socialization habits. Some of the most potent and prevalent symbols of pop culture include money, cars, beautiful and hypersexualized women, romantic love, sex, specifically sex without/outside marriage (adultery and fornication), the idea to ‘be yourself,’ the idea ‘Yolo,’ meaning you only live once, socially unrestrained freedom; family as regressive to individual freedom and social progress, and religion as antiquated, among others. Further elaboration of these themes reveals some of our values in action as a society:

We live in a products economy and all our products are dispensable. Nothing is to be reused, and reusable things are only to last for a very short time before being thrown away and replaced. These include coffee cups, water bottles, clothes based on ephemeral clothing trends, cosmetics, and electronics.More and more of our communities are virtual, as we slowly convert more of our communications to online and social media platforms. One of the gravest dangers of this—and this is not to advocate pulling the plug on technology or social media, but rather to promote responsible, moral, and intelligent use of technology—is that we spend more time on our appearances (i.e., profiles, selfies, check-ins, etc.) than on reflecting on souls for the purpose of self-improvement. A gaze that is turned outwards cannot simultaneously see inward. The latter is something that can only be done in quietude, away from the popular gaze, in intimate dua with Allah and/or with the guidance of a spiritual teacher. Virtual communities also don’t have mechanisms by which we can hold one another accountable—something that families, masaajid and churches, and neighborhoods can do.Sexual relations, according to pop culture, are completely unfettered. There is no restriction on sexuality other than mutual consent, and this has become the absolute norm. Various other forms of cultural expression, habit, and symbol enforce this. Anyone with a smartphone and the inclination can engage in fornication or adultery. This ‘freedom’ is actually the removal of our mutual responsibility to enjoin the keeping of truth and patience in adversity.[20] Popular poetry, found in song lyrics, promotes a dismal relationship cycle (or worse, a hookup cycle) in which: a romantic or sexual attraction is sparked ➔ a felicitous coupling occurs ➔ heartbreak (or recycling of partner without heartbreak) ensues, due to infidelity (or some other power to exercise preference) ➔ a new partner helps to soothe the distaste and suffering of the previous cycle/a romantic or sexual attraction is sparked ➔ the cycle perpetuates ad infinitum.All cultural notions of power are material; that is, they involve power over something tangible—like people, money, objects, territory, markets, etc. It is the power of conquest, specifically the conquest to fulfill and maximize pleasure, whether that pleasure be buying beautiful clothes, trying a new makeup trend, smoking or drinking, or being in yet another romantic relationship. Or, at the level of socioeconomic priorities, the power to achieve upward economic mobility, financially take over a competing company, or invade and occupy a foreign sovereign country.There is no concept in our popular culture that true power is spiritual power. That power lies not in fulfilling pleasures, but in transcending being ruled by them. There is no concept in pop culture that true power is power over the lower self; only power (of the nafs) over others is considered impressive. Religion is considered the opposite of freedom because it can hold you back from what is seen as being your “true” self in one way or another. Increasingly, the only occasion in which pop culture affords value to religious experience is when its expression is somehow being turned on its head. Examples include a gay church, or “finding God” in places and experiences that are inimical to what God commands. But these are only the negative aspects of pop culture. Above all, pop culture is a field of contestation. Culture can be a battleground of competing values. While we live in a largely throw-away society, at the same time there are movements to reduce waste, to cultivate urban farms, and to recycle and end the use of plastic bags. While many people have switched to virtual communities and social media communication, so too are there community associations, food co-ops, and other initiatives to restore more traditional forms of community. Just as sexuality has become an appetite completely swollen out of proportion, as well as anonymous and completely untethered from the familial obligations that Allah the Exalted intends, so too do people continue to get married, aim at monogamy, and uphold the sanctity of new life. Poetically, while scores of recording artists extol fornication, sexual violence, sensationalized alcoholism, and crass individualism, Damien Marley counters the current by promoting a godly life, marriage, and raising babies; Kanaan defines life’s struggle as taking care of your family, neighbors, and nation; and Sevin raps about “being in love” with God “unrepentantly” and how the only enemy that needs to be defeated is his inner (i.e., lower) self. Culture is a contest, so both sets of competing values in these examples constitute it. However, certain values are more normalized than others; i.e., one finds majority and minority positions. We find that an overwhelming quantity, and increasingly invasive in its forms (i.e., internet-based), of cultural production is secular and promotes nafsi excess. But this same cultural landscape can and ought to become more spiritualized and upright. In this land of good trees and bad trees, we ought to be planting far more good seeds.

Planting good seeds in the battleground of values

In order to map a course of action for planting good cultural seeds, it is first crucial to survey the values and underlying philosophies of life that nourish the cultural products all around us.

| Pop Culture Product | Value / Philosophy |

Cash/money

Never-ending acquisition

of products for consumption | Greed for more and more

Lack of charity (global supply chain)

Fear of death ➔ No belief in afterlife |

| Power = material | Justice as law of the strong

(political realism)

Earthly kingdom > Afterlife |

| Virtual communities | No accountability to others ➔ Self-invention

(vs. co-constitution)

The self as Sovereign

(all rights; no responsibilities) |

| Pleasure-drivenYOLO | I ought ➔ I want

No consequential belief in afterlife |

| Religion =/= Freedom | Freedom from submission,

not freedom through submission;

indifference to God |

| Unfettered sexuality | All of the above + Reign of the nafs |

The above chart indicates some of the roots of popular culture today. Our societal drive to acquire maximal monetary wealth, coupled with our never-ending acquisition of products for temporary consumption, indicates that we have become a people of insufferable greed. Our habits are an example of the divine description in Surat At Takathur of those obsessed with greed for more and more.

[21] Our runaway materialism is also associated with a lack of charity within the human family. A cursory study of the global supply chain (extraction, production, distribution, consumption, and disposal)

[22] shows how nations of people must be made peripheral to the human civilizational story and suffer unlivable poverty so that others in the metropoles of the world may become central actors, living affluently and consuming conspicuously. On the level of spiritual psychology, rampant consumerism and love of wealth reveal a fear of death.

[23] As the Prophet Muhammad, may Allah’s peace and blessings be upon him, said: “If the son of Adam had a valley full of gold, he would like to have two valleys, for nothing fills his mouth except dust. And Allah forgives whoever repents to Him.”

[24] For it is only when we think we will live forever (or that what follows earthly life is inconsequential) that we mistakenly resort to building earthly kingdoms that we believe might preserve us after death.

[25]The cultural norm that all power is material has deep roots in Western political thought (though this strand has always been contested). In Plato’s Republic, the character of Thrasymachus answers Socrates’ main question (What is justice?) with the idea that justice is the interest of the powerful. In Gorgias, the character of Callicles similarly maintains that it is natural law for the strong to dominate the weak. Later political philosophers in the Western tradition who continued the political realism of this position include Machiavelli, Hobbes, and Locke. Political realism’s underlying philosophy of life privileges the earthly life over the afterlife. However, as Muslims, we know that all earthly power (no matter how sprawling or impressive) is only conferred by the Most Powerful, and is, ultimately, a spiritual test.

We find in virtual communities many opportunities to spread good words and provoke good works. But the sordid side of this young phenomenon is the lack of accountability. Virtual communities (activated through smart technology, social media, and the internet) provide a cloak of anonymity for those whose whisperings require it. They feed the mammoth delusion that we invent ourselves: filtering faces; editing speech acts; adding and subtracting people from our social circles at will; etc. Rather, human beings constitute one another in a way that cannot nor ought be detangled. Virtual communities can easily eclipse the fullness of our social nature for those who are not vigilant.

The broader context that nurtures these cultural products and processes is the riotous rank that pleasure enjoys. It is no hyperbole to claim that much of our popular culture celebrates decadence and hedonism. Ethics philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre argues that, over the course of philosophical and moral permutations, the syllogism for practical actions transformed from the traditional

I ought to the materialist

I want.

[26] Whereas practical action previously had to stem from some moral imperative, lower desires and personal preferences alone now provide sufficient justifications for the decisions we take, without regard to the (or

any) moral law. This philosophy of life helps to explain the popular mantra

yolo! Signifying that

you only live once, the phrase is uttered in contexts where caution will be thrown to the wind, and living a full life means liberating oneself from traditional restraints. Such motivation bypasses not only a belief in an afterlife (ultimate accountability), but also descends another level to disregard immediate consequences.

In popular cultural expressions, we find that religion, religious leaders and practitioners, and even prophets are often caricatured or reviled. When these archetypes are presented as subverting traditional religious norms, they are celebrated for being forward-thinking. To provide a commonplace example, the Abrahamic faiths all prohibit fornication, adultery, and homosexual acts—and these prohibitions violate the unfolding liberal sexual freedoms of our age. Rather than problematize, think through, and reformulate what tolerance and pluralism mean in a shared and contested terrain of adyaan (plural of din), religion is made to bend to prevailing sexual mores. Good religion will evolve with the river of time in its conception of human sexuality; bad religion will remain recalcitrant, antiquated, and unfree. At its roots, this debate makes clear that popular culture is indifferent to the Creator, and will be determined by human qua human deliberations alone.

The cultural norm of unfettered sexuality contains within it many of the motivations and values elucidated above, and resolutely affirms the reign of the

nafs, or lower appetites. As Shaykh Mokhtar Maghroui succinctly stated, freedom in a secular sense is the freedom of the

nafs from the

khalq (creation)

; but freedom for us (Muslims) is freedom of the

qalb (the intuitive substance that can know Allah or become corrupt) from the

nafs.[27] A political guess as to why public regulations on sexuality have been relinquished over time is that increasing unfreedom, specifically tyrannies and juridifications of market and state, risk massive revolt and overthrow—to which unhinged sexual freedom provides a palliative sedation.

If these are some of the roots of harmful popular culture fruits, what is the implication? What ought we do?