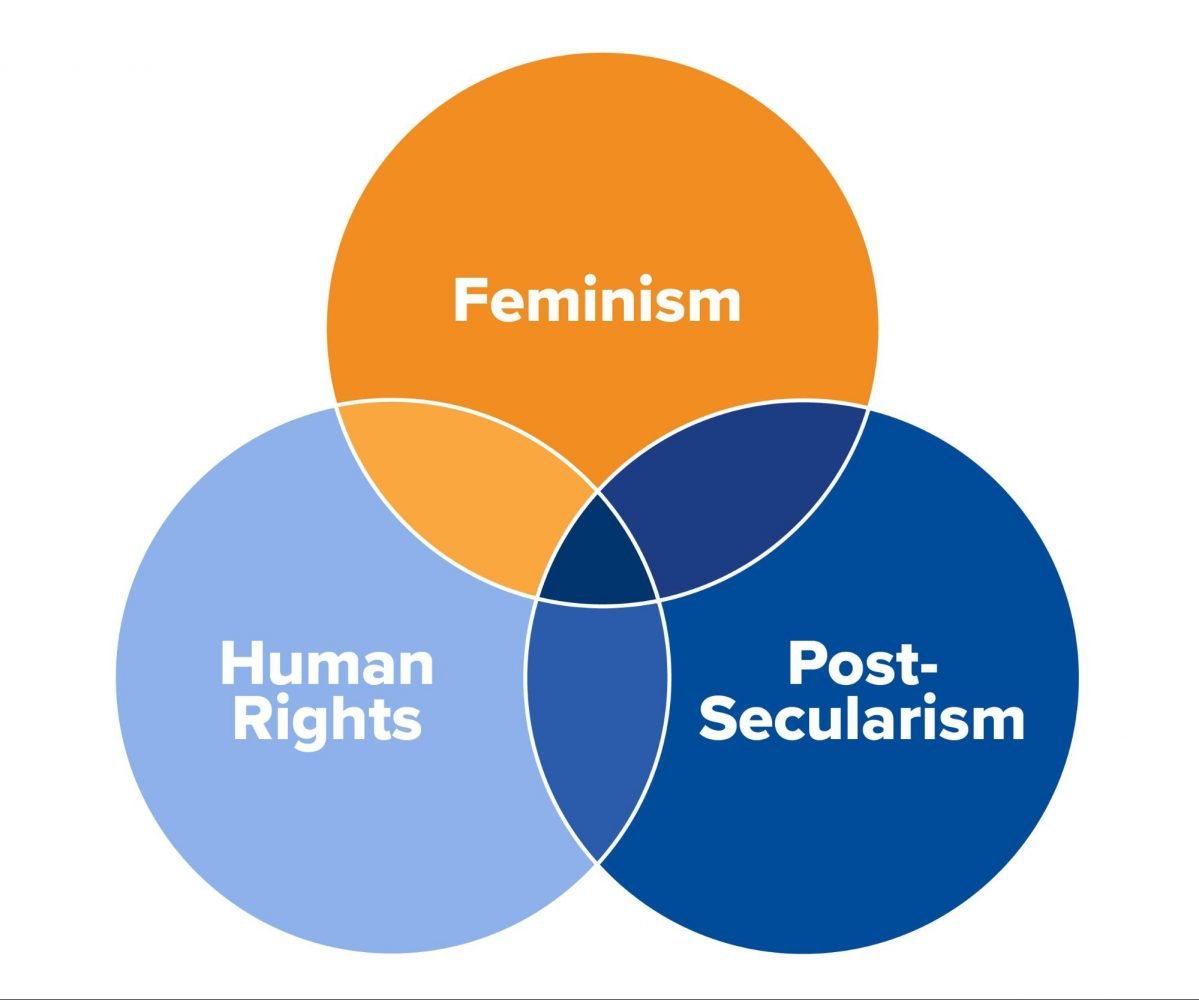

Balancing Feminism, Human Rights, & Faith

For more on this topic, see Gender and Islam

Abstract

Introduction

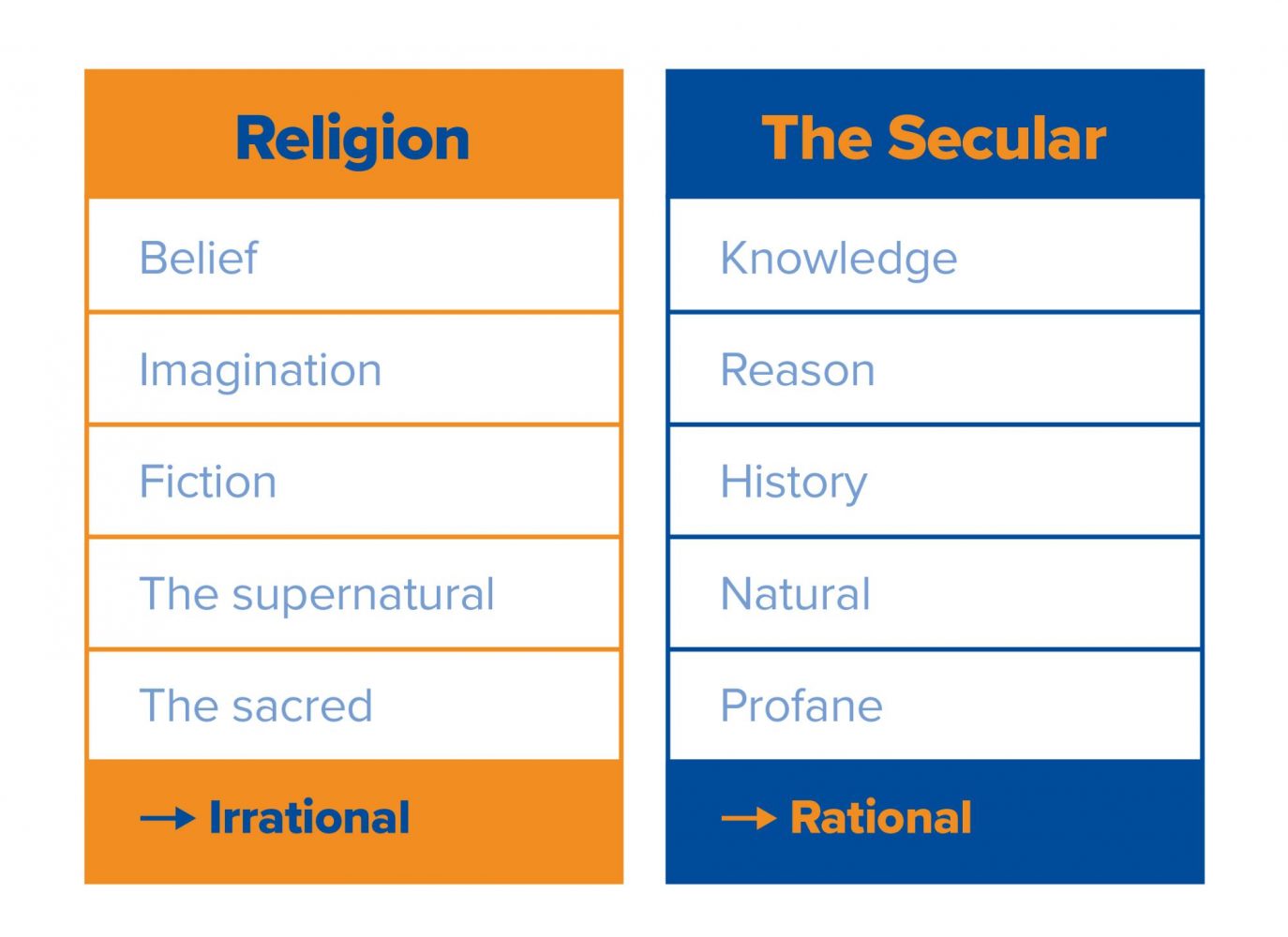

Theme I: (Secular) religion

If the nation‐state is conceived as an expression of sovereign will, then the Aristotelian final cause of its existence is nothing more than its perpetual existence. The nation-state exists for its own sake. It is a means to no other end.[23]

Theme II: Knowledge and (un)certainty

Theme III: The human being and freedom

[A]ll emphasize ‘democracy’ and the values that underpin it as the larger discursive frame in which ideas of secularism and secularity can be redefined with emancipatory intent. This common ground in democracy is, I argue, at the heart of non‐oppressive articulations of feminism that both retain a commitment to norms of gender equality and human rights and actively respect women’s differences, including in relation to religious identity.[37]

Yes, religious cultures must adapt, with difficulty, to four inescapable conditions of modern secular life—the presence of other strong faiths, the authority of science, the universalist mode of positive law, and a pervasive profane popular morality. But they should not be subjected to unfair psychological or socio-cultural pressure in so doing. Postsecular culture must therefore openly recognize religion not just as a set of private beliefs but as an all‐embracing source of energy for the devout, and, actually, for society in general too. Except at the highest institutional levels, the case goes, the demand that people cease to speak politically in religious terms must be dropped.[42]

Its imperial mission aside, the discourse (and organized campaigns) of human rights has more of a symptomatic relationship to neoliberal global capitalism: it broaches moments of critique; it attempts to inoculate against neoliberalism’s worst excesses; sometimes it pretends to offer something almost like a counter-public, yet it continues to operate insistently outside the economic sphere, the most important of neoliberalism’s theaters of operations.[57]

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance.[64]

Freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals, or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.[65]

Freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals, or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.[71]

Conclusion: Religion as din

is an argument extended through time in which certain fundamental agreements are defined and redefined in terms of two kinds of conflict: those with critics and enemies external to the tradition who reject all or at least key parts of those fundamental agreements, and those internal, interpretative debates through which the meaning and rationale of the fundamental agreements come to be expressed and by whose progress a tradition is constituted.[78]

Instead of something that emerges in a dialogical process and whose direction cannot be forecast readily, these world order values are taken as given. These values are then used to distinguish those agents fostering civility from those whose incivility must be purged to create a global order.[87]

The primary significations of the term din can be reduced to four: (1) indebtedness; (2) submissiveness; (3) judicious power; (4) natural inclination or tendency…The verb dana which derives from dinconveys the meaning of being indebted…In the state in which one finds oneself being in debt, that is to say, a da’in it follows that one subjects oneself, in the sense of yielding and obeying, to law and ordinances governing debts, and also, in a way, to the creditor, who is likewise designated as a da’in. There is also conveyed in the situation described the fact that one in debt is under obligation, or dayn. Being in debt and under obligation naturally involves judgment: daynunah, and conviction: idanah, as the case may be. All the above significations including their contraries inherent in danaare practicable possibilities only in organized societies involved in commercial life in towns and cities, denoted by mudun or mada’in. A town or city, a madinah, has a judge, ruler, or governor, a dayyan. Thus already here, in the various applications of the verb dana alone, we see rising before our mind’s eye a picture of civilized living; of societal life of law and order and justice and authority. It is, conceptually at least, connected intimately with another verb maddana which means: to build or to found cities: to civilize, to refine and to humanize; from which is derived another term: tamaddun, meaning civilization and refinement in social culture.[88]

Notes

[1] See Josephine Donovan, Feminist Theory: The Intellectual Traditions (New York: Continuum, 2000).

[2] Alasdair MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1988), 181-195; Zara Khan, “Refractions Through the Secular: Islam, Human Rights, Universality” (doctoral dissertation, City University of New York Graduate Center, 2016), 36-40 and 77-79, CUNY Academic Works url: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1618/; and Nour Soubani, “Does Islam Need Saving? An Analysis of Human Rights,” Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research (2017), https://yaqeeninstitute.org/en/nour-soubani/does-islam-need-saving-an-analysis-of-human-rights/.

[3] In actuality the UDHR did not represent a global consensus, but rather was the consensus of the Euro-American global elites after World War II. As Joseph Massad states, “The 750 million people the United Nations left colonized voted with their feet for a cosmopolitanism that implied their collective emancipation with more assurance and with more practical meaning than international human rights did.” Joseph Massad, Islam in Liberalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 379.

[4] See J. C. D. Clark, “Secularization and Modernization: the Failure of a ‘Grand Narrative’,” The Historical Journal 55, no. 1 (2012): 161‐194.

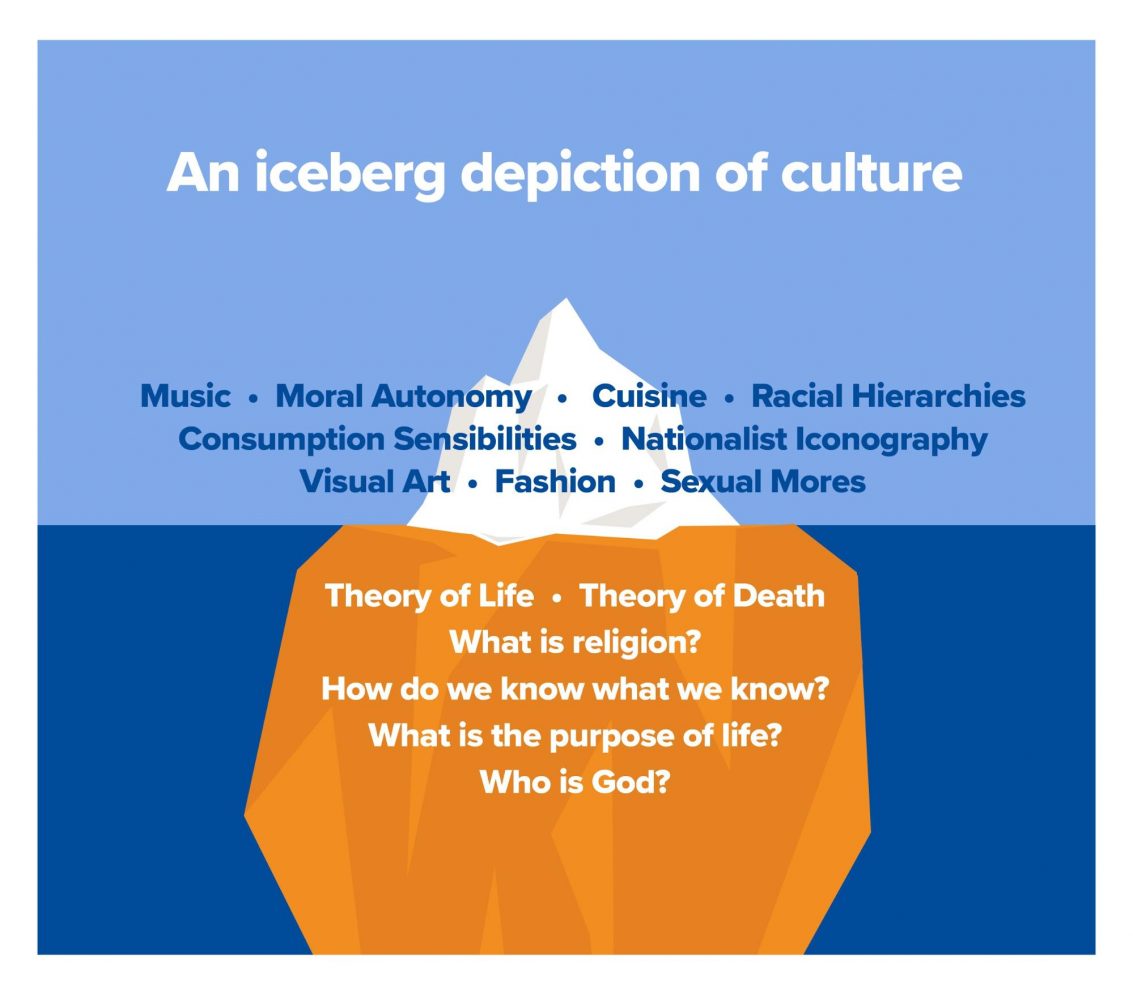

[5] Examples include: materialist worldview; capitalist worldview; belief in linear, infinite progress; the reign of science and technology; ostracism from and vilification of death in public consciousness; cosmopolitan aesthetics; etc.

[6] Edward Hall, Beyond Culture (New York: Anchor, 1976).

[7] Quoted in Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas, Islam and Secularism (Lahore: Suhail Academy, 1978), 17.

[8] Ibid., 18.

[9] Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003).

[10] See William Cavanaugh, The Myth of Religious Violence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[11] Ibid., 59.

[12] Jonathan Z. Smith, “Religion and Religious Studies: No Difference At All,” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal 71, no. 2/3 (1988): 231-244. Elsewhere, Smith argues that: “With respect to practice, the history of religions is, by and large, a philological endeavor chiefly concerned with editing, translating and interpreting texts, the majority of which are perceived as participating in the dialectic of ‘near’ and ‘far.’ If this is the case, then our field may be redescribed as a child of the Renaissance.” See Jonathan Z. Smith, Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2004), 364.

[13] Tomoko Masuzawa, The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in The Language of Pluralism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 20.

[14] Cavanaugh, Myth, 62.

[15] Ibid., 64.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., 64-65.

[18] Ibid., 65-68.

[19] See ‘Theme III’ below.

[20] Asad, Formations, 199.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Wael Hallaq, The Impossible State: Islam, Politics, and Modernity’s Moral Predicament (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 49.

[23] Ibid., 28.

[24] Ibid., 107.

[25] Ibid., 28. See also Cavanaugh, Myth 4‐5, 8, 10, 56, and especially 122.

[26] Asad, Formations, 16.

[27] Ibid., 25.

[28] On the genesis of the secular category of ‘the social’ in 19th century England, see Ibid., 189-190. Of ‘agency’ Asad states: it “is not a natural category…successive uses of this concept (their different grammars) have opened up or closed very different possibilities for acting and being. The secular, with its focus on empowerment and history‐making, is clearly one of those possibilities.” Ibid., 73.

[29] A powerful and lucid unmasking of the false claim that we live in a post-racial America is found in Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color Blindness (New York: The New Press, 2010).

[30] Asad, Formations, 30.

[31] Ibid., 43.

[32] G.W.F. Hegel, Philosophy of Right, trans. S. W. Dyde (London: George Bell and Sons, 1896).

[33] Asad, Formations, 192-193.

[34] Ibid., 179-180.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid., 180.

[37] Niamh Reilly, “Rethinking the Interplay of Feminism and Secularism in a Neo‐secular Age,” Feminist Review 97 (2011): 5‐31.

[38] See the last section of Theme I above.

[39] Asad, Formations, 184.

[40] Ibid., 186‐187.

[41] Ibid., 185.

[42] Jurgen Habermas, “Religion in the Public Sphere.” European Journal of Philosophy 14, No. 1 (2006): 1-25; specifically 7-10.

[43] See Stefan Rummens, “The Semantic Potential of Religious Arguments: A Deliberative Model of the Postsecular Public Sphere,” Social Theory and Practice 36, no. 3 (2010): 385‐408, specifically 390‐391.

[44] Rummens states: “Recognizing the autonomy of moral and political individuals implies that they are free to shape and reshape their own values and preferences in response to the changing circumstances of the historical society in which they are situated.” Ibid., 395.

[45] Asad, Formations, 199.

[46] Reilly, “Rethinking,” 26.

[47] See for example Charles Sampford, “The Potential for a Post‐Westphalian Convergence of ‘Public Law’ and ‘Public International Law’,” in Sanctions, Accountability and Governance in a Globalised World, eds. Jeremy Farrall and Kim Rubenstein (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 53‐54.

[48] Peter G. Danchin, “Whose Public? Which Law? Mapping the Internal/External Distinction in International Law,” Publication of the University of Maryland School of Law 38, (2010), accessed April 20, 2015. The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1662569. For an example of ‘liberal anti-pluralism’ theorizing, see Gerry Simpson, “Two Liberalisms,” European Journal of International Law 12, no. 3 (2001): 537-571. Simpson states: “Liberal anti‐pluralism finds its most prominent manifestation in the recent work of Fernando Teson, Michael Reisman, Thomas Franck, John Rawls and Anne‐Marie Slaughter where, in each case, the internal characteristics of a state has the potential to determine that state’s standing in the family of nations,” 537. These internal characteristics can include regime type, the rights of individuals and democracy, with an emphasis on popular sovereignty and civil rights. Liberal anti‐pluralism, says Simpson, undermines sovereign equality and ontologically privileges individuals, 539-542 See also Edward N. Megay, “Anti‐Pluralist Liberalism: The German Neoliberals,” Political Science Quarterly 85, no. 3 (1970): 422-442. Megay argues that liberalism is not necessarily pluralist, nor is pluralism necessarily liberal. He indicates that German neoliberal views regarding social freedom and power are logically consistent with anti‐pluralism, and can result in elitist governments led by technocrats.

[49] Danchin, Whose Public?, 29.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid., 32. The intersubjective nature of international law is important because it achieves reconciliations and reaches political settlements between “conflicting claims to freedom of differently situated subjects and the divergent assertions of right and justice to which they continually rise.”

[52] Massad, Islam, 111-112.

[53] Ibid., 127.

[54] Ibid., 127‐128.

[55] Ibid., 135‐138.

[56] Ibid., 145.

[57] Ibid., 133.

[58] The theory of multiple modernities developed to explain diversity among societies in light of modernization theory’s emphasis on their similarities along the supposed singular path to modernization. Modernization theory thus stresses convergence while multiple modernities stresses divergence. See Volker H. Schmidt, “Modernity and Diversity: Reflections on the Controversy Between Modernization Theory and Multiple Modernists,” Social Science Information 49, no. 4 (2010): 511-538.

[59] Reilly, Rethinking, 26-27. See also Irene Oh, The Rights of God: Islam, Human Rights and Comparative Ethics (Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2007).

[60] Reilly, Rethinking, 25.

[61] Charles W. Mills, The Racial Contract (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997). He states: “The Racial Contract is that set of formal or informal agreements, or meta‐agreements (higher‐level contracts about contracts, which set the limits of the contracts' validity) between the members of one subset of humans, henceforth designated by (shifting) ‘racial’ [phenotypical/genealogical/cultural] criteria C1, C2, C3…as ‘white,’ and coextensive (making due allowance for gender differentiation) with the class of full persons, to categorize the remaining subset of humans as ‘nonwhite’ and of a different and inferior moral status, subpersons, so that they have a subordinate civil standing in the white or white‐ruled politics the whites either already inhabit or establish or in transactions as aliens with these polities, and the moral and juridical rules normally regulating the behavior of whites in their dealings with one another either do not apply at all in dealings with nonwhites or apply only in a qualified form (depending in part on changing historical circumstances and what particular variety of nonwhites involved), but in any case the general purpose of the Contract is always the differential privileging of the whites as a group with respect to the nonwhites as a group, the exploitation of their bodies, land, and resources, and the denial of equal socioeconomic opportunities to them. All whites are beneficiaries of the Contract, though some whites are not signatories to it,” 11.

[62] Reilly, Rethinking, 26.

[63] The neutrality/universality claim is made by the following prominent approaches to human rights today: 1) the political/minimalist approach to human rights, represented by John Rawls (“The Law of Peoples,” Critical Inquiry 20, no. 1 (1993): 36‐68, and “Justice as Fairness: Political not Metaphysical,” Philosophy & Public Affairs 14, no. 3 (1985): 223‐251), Simon Caney (“Humanity, Associations, and Global Justice: In Defence of Humanity‐Centred Cosmopolitan Egalitarianism,” The Monist 94, no. 4, (2011): 506‐534, and “Global Interdependence and Distributive Justice,” Review of International Studies 31, no. 2 (2005): 389‐399), and Charles Beitz (The Idea of Human Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); 2) the moral autonomy approach advocated by Alan Gewirth (The Community of Rights (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996) and James Griffin (On Human Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008)); and 3) the human dignity approach argued by Jack Donnelly (Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003).

[64] See The Universal Declaration on Human Rights, http://www.un.org/en/universal‐declaration‐human‐rights/.

[65] Article 18.3. See full text of ICCPR at: http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx.

[66] Ibid., ICCPR Article 18.4.

[67] Ibid., ICCPR Article 26.

[68] Ibid., ICCPR Article 27.

[69] Insofar as the ICESCR advances the right of all people to self‐determine (politically, economically, socially and culturally), have access to technology for such development, and enjoy gender equity in these and other rights, it does so in a manner that doesn’t discriminate on the basis of religion. See Article 2.2. See full text of ICESCR at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx. Like the ICCPR, the ICESCR also defines the limit of the rights it enumerates. States party to the covenant may subject these rights to such limitations as “determined by law only in so far as this may be compatible with the nature of these rights and solely for the purpose of promoting the general welfare in a democratic society.” See ICESCR Article 4.

[70] Available at: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/36/a36r055.htm. This resolution lists the freedoms associated with freedom of religion in both the realm of the individual’s conscience and the communal, institutional aspects of religious practice (i.e., confession, observance, producing literature and proselytization, observing holidays, congregating, establishing places of worship, parental rights in religious upbringing of children, etc.).

[71] Ibid., Article 1.3.

[72] See Samuel Moyn, “From Communist to Muslim: European Human Rights, the Cold War, and Religious Liberty,” South Atlantic Quarterly 113, no. 1 (2014): 63-86.

[73] Ibid., 65-66. For an analysis of Islam and Muslim women in the European Court, see also Carolyn Evans, “The ‘Islamic Headscarf’ in the European Court of Human Rights,” Melbourne Journal of International Law 4 (2006), accessed July 4, 2016, http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/MelbJIL/2006/4.html.

[74] Joan Wallach Scott, The Politics of the Veil (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007): 26-50.

[75] Locke stated: “[T]he church itself is a thing absolutely separate and distinct from the commonwealth. The boundaries on both sides are fixed and immovable. He jumbles heaven and earth together, the things most remote and opposite, who mixes these two societies, which are in their original, end, business, and in everything perfectly distinct and infinitely different from each other.” John Locke, Concerning Toleration (1689) quoted in Cavanaugh, Myth, 82.

[76] Khan, Refractions.

[77] Ibid.

[78] MacIntyre, Whose Justice, 12.

[79] Ibid., 6.

[80] Ibid., 327.

[81] Ibid., 333.

[82] Ibid., 335.

[83] Ibid., 349.

[84] Talal Asad, “Thinking About Tradition, Religion and Politics in Egypt Today,” http://criticalinquiry.uchicago.edu/thinking_about_tradition_religion_and_politics_in_egypt_today/.

[85] Ibid. See also Saba Mahmood, Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005). Mahmood’s famous treatment of the female pietists of Egypt’s Islamic revival operationalizes this exact rendering of ‘tradition,’ as she demonstrates that the subjects’ agentive motivations are embodied and performed through the vehicle of piety and the pedagogy of religious instruction.

[86] Asad, Thinking About. See also Sherman A. Jackson, Islam and the Blackamerican: Looking Toward the Third Resurrection (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). Jackson argues, in evaluating the inferior position afforded to Blackamerican Muslims by their immigrant counterparts (Arab and South Asian migrant Muslims to the U.S.), that failure to transfer religious authority in a timely fashion has resulted in the reification of Immigrant Islam’s ‘false universals’— here serving as example of rupture and continuity in Islamic tradition in the United States.

[87] David L. Blaney and Naeem Inayatullah, “Neo‐Modernization? IR and the Inner Life of Modernization Theory,” European Journal of International Relations 8, no. 1 (2002): 103‐137, specifically 128.

[88] Syed Muhammad Naquib al Attas, Prolegomena to the Metaphysics of Islam: an Exposition of the Fundamental Elements of the Worldview of Islam (Kuala Lumpur: National Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, 2001), 42-44.

[89] Abdal Hakim Murad, Crisis of Modern Consciousness, posted by A. Karim Omar (January 20, 2012, Youtube), http://youtu.be/RWOKaOb33K4.

[90] Judith Butler refers to the “instrumentalization of the freedom norm” by state power as the tendency of modern Western states to use sexual rights, specifically LGBTQ rights, to exclude non-normative subjects, specifically Muslims, from citizenship, socially persecute, or torture them. See Judith Butler, “Sexual Politics, Torture, and Secular Time,” British Journal of Sociology 59, no.1 (2008): 1‐23.

[91] “Freedom” was the moral, political justification given for war and invasion of Afghanistan in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. See Zillah Eisenstein, Against Empire: Feminisms, Racism, and the West (London: Zed Books, 2004). See Scott, Politics of the Veil, for how France has persecuted modern Muslim subjects, specifically in the context of the headscarf prohibition against women.

[92] See Introduction above.