§1. This is a kitāb (writ, prescript) from Muḥammad <the Messenger of Allah> between the muʾminūn (Believers) and muslimūn (Muslims) of the Quraysh and Yathrib and those who join them, <settle with them,> and make jihād (armed struggle) alongside them.

§2. They are one people to the exclusion of all other people (innahum ummah wāḥidah min dūn al-nās).

Ummah. The opening clauses of the Pact of the Believers establish the ummah as a religious and political community. Hamidullah translates ummah here as a political community, but it is evident that not only political order but also active struggle for faith is a constituent of the community.

Generally, ummah could mean, as it does in places in the Qur’an, (i) the community of the followers of all prophets since the beginning of time. On other occasions, (ii) it means the community that a prophet preaches to in any given era, and hence inclusive of his opponents (the more common term for which was qawm). For instance, in a hadith in Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, the Messenger ﷺ said, “By Him who holds Muḥammad’s soul in His hand, anyone who hears of me from this ummah, a Jew or a Christian, then dies without believing in what I have brought will be among the people of Fire” (Muslim no. 153), which means that in one meaning the term ummah encompasses all human beings after his commission until the end of time. This is glossed by scholars as ummat al-daʿwah. However, (iii) in this document, the Prophet ﷺ defines the ummah in the way that becomes the primary meaning of the term for all time, in accordance with the Qur’anic verses that were revealed about this time: “O you who believe… You are the best ummah…” (3:102-110) and “Thus we have made you the middlemost/best ummah…” (2:143). In this context, ummah could only mean a community defined by belief in and support of the Prophet Muḥammad’s ﷺ mission. The law revealed in the ensuing years was addressed to this community and its posterity, and through it to all humankind until the end of time. This community is addressed in the Qur’an as al-muʾminūn, the Believers, or yā ayyuhā alladhīna āmanū: O ye who believe.

Muslim/muʾmin. The Qur’an rarely employs the term muslim, which is why the distinction between muʾminūn and muslimūn in the first clause of this document is notable. Although their referents may overlap (ʿaṭf al-ʿāmm ʿalá al-khāṣṣ), it is more likely that the two words have slightly different connotations, and the best way to understand them is in concentric circles: all muʾmins are muslims but not the other way around. When used in an unqualified form, the term muʾminūn is reserved in the Qur’an, as in this document, for the true believers and followers of a prophet—be it Muhammad, or Moses, upon them be peace—in their time. Contrary to misconceptions in some Orientalist theories, it is never employed to mean generic believers or monotheists, but only the true followers of God’s prophets. Revealed about this time, Sūrat al-Nisāʾ declared those who disbelieve in some prophets while believing in God and selected prophets to be “the truly unbelieving” (4:150-1). In this sense, it is a term at times of identity (as it names a group) and at other times of description, approval, and praise, and at times both (as in 4:136). For instance, in 2:62 and numerous other places, the Qur’an refers to the Prophet Muhammad’s followers as ‘those who believed (āmanū)’ while contrasting them to the Jews and the Christians. Elsewhere, the righteous followers of Moses and other prophets who aided them in their prophetic mission are referred to as ‘believers’ or ‘those who believed’ (2:213; 2:249; 7:88). After they acquire their historical identity that takes them away from adherence to their prophet, rather than the ‘believers’ the Christians are always called Naṣārá (Nazarenes), and the Jews Yahūd (or alladhīna hādū) or, in historical references, Banū Isrāʾīl, and both more generally ‘the People of the Book.’ In one place, when reprimanding the Jews and the Christians for failing to follow Abraham’s true monotheism and thus joining the Prophet Muhammad’s ﷺ mission, the Qur’an declares that “The closest associates of Abraham are those who followed him, and this prophet and those who have believed” (3:57), which could only make sense if those who have believed are an identifiable group distinct from the Jews and the Christians.

Only twice in the document (and once more in AU’s version) is the group muslimūn mentioned to refer to some followers of the Prophet ﷺ. This accords with the Qur’anic distinction as in 49:14 (“The bedouins say, We have become muʾmin. Say [to them], You have not yet become mu’min, but you have become muslim, for īmān has not yet entered your hearts”). Since 49:14 refers to a later incident (concerning the nomadic tribe of Banū Asad b. Khuzaymah whose deputation came to declare their faith in 9 AH) and the Kitāb was probably concluded during the third year of the Hijra or earlier, this would mean either that the Prophet ﷺ had already made this distinction between muʾmin and muslim from the outset, or else that the Kitāb was updated later to reflect this distinction.

Yathrib. This was the name of the settlement to which the Prophet ﷺ migrated. The name

al-Madīnah (Medina) is generally understood to have been coined after the Prophet’s migration, when it began to be called

Madīnat al-Nabī (the city of the Prophet) and then shortened to

al-Madīnah. Some historians suggest, however, that the name

al-Madīnah is Aramaic in origin and had been one of this town’s ancient names.

[10]§3. The Emigrants from the Quraysh keep to their tribal organization and leadership, cooperating with each other regarding blood money (yataʿāqalūn) and related matters and ransoming their captives (yafdūn ʿāniyahum) according to what is customary and equitable among the Believers.

Here, the document reaffirms the tribal organization (II:

rabaʿatihim AU:

rabāʿatihim), but in a modified form. Ibn Sayyid al-Nās explains

rabaʿah or

rabāʿah/ribāʿah as “the state in which they were when Islam came to them,” namely, their tribal organization.

[11] In contrast to the first two clauses that are concerned with faith, this one addresses what we may label political and administrative grouping,

ʿāqilah. More precisely, the

ʿāqilah is the blood-money group—the solidarity group that must pay compensation for a crime committed by one of their number. All the Emigrants together formed one such group, thus operating as a single clan, even though they had originally come from the various clans of the Quraysh and non-Quraysh in Mecca, including even some non-Arabs. Thus, although the

membership of this new clan was defined by faith, its

structure was pre-Islamic, for Islamic laws concerning blood relations, marriage, inheritance, and filial ties had yet to be revealed.

[12] §4-§11. The Banū ʿAwf keep to their tribal organization and leadership, cooperating with each other regarding blood money and related matters and ransoming their captives according to what is customary and equitable among the Believers.

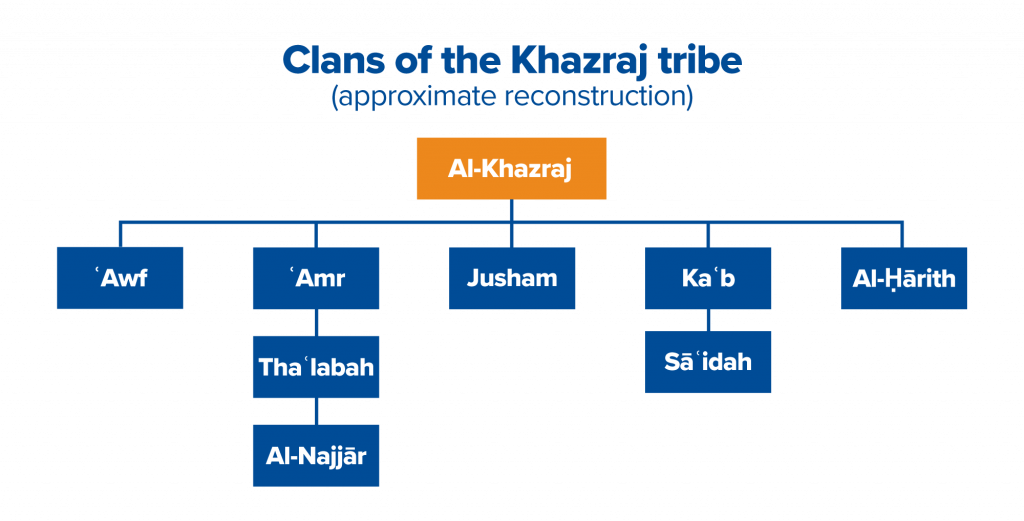

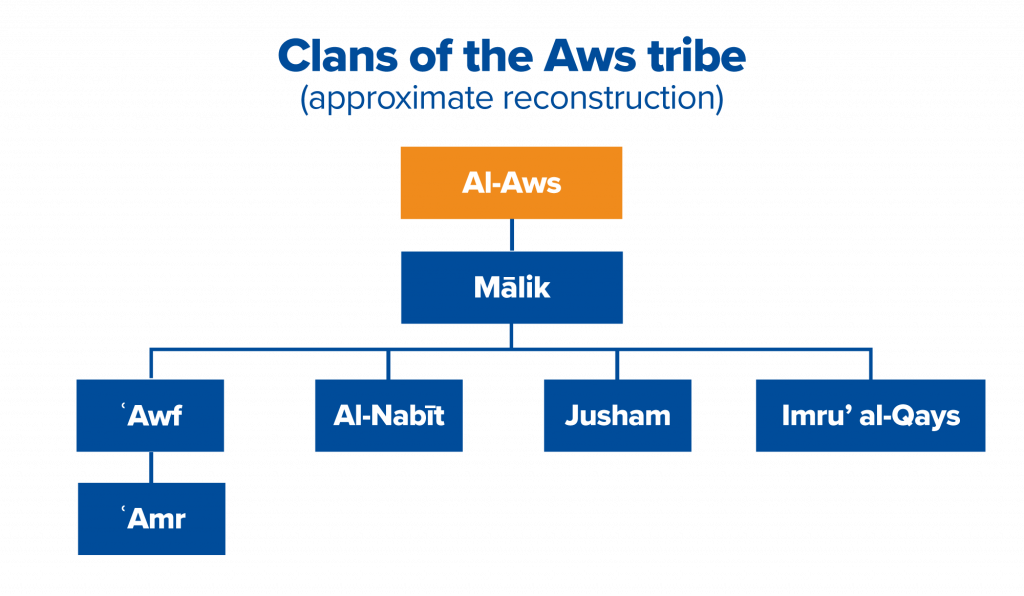

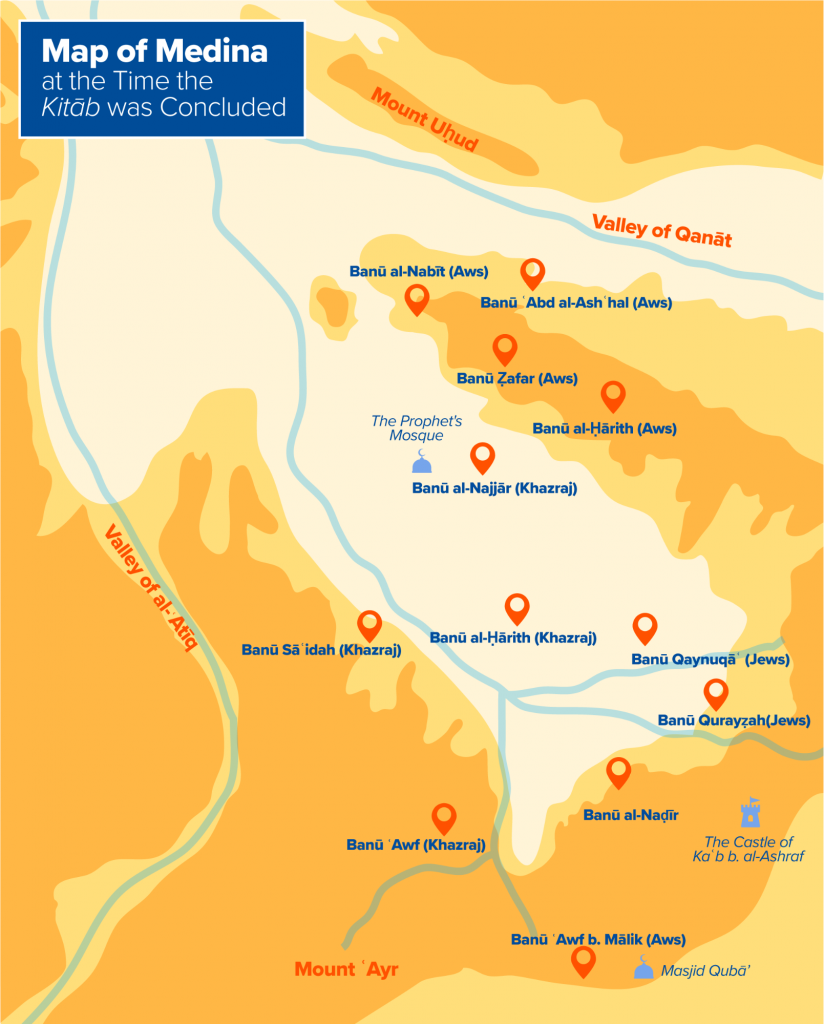

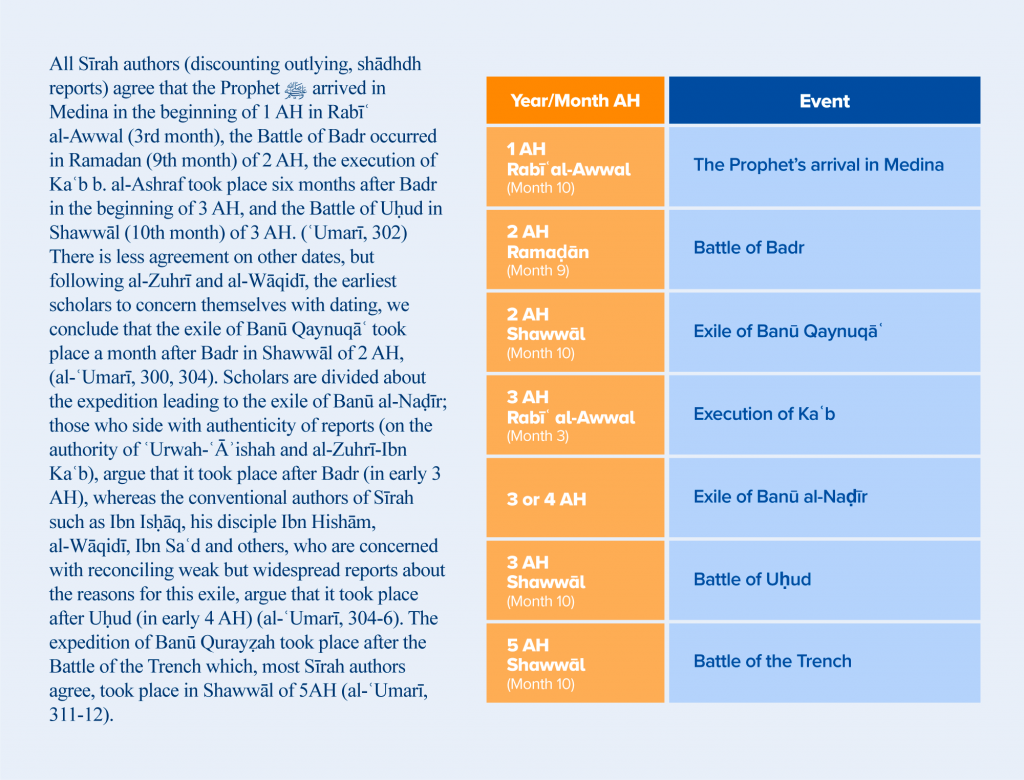

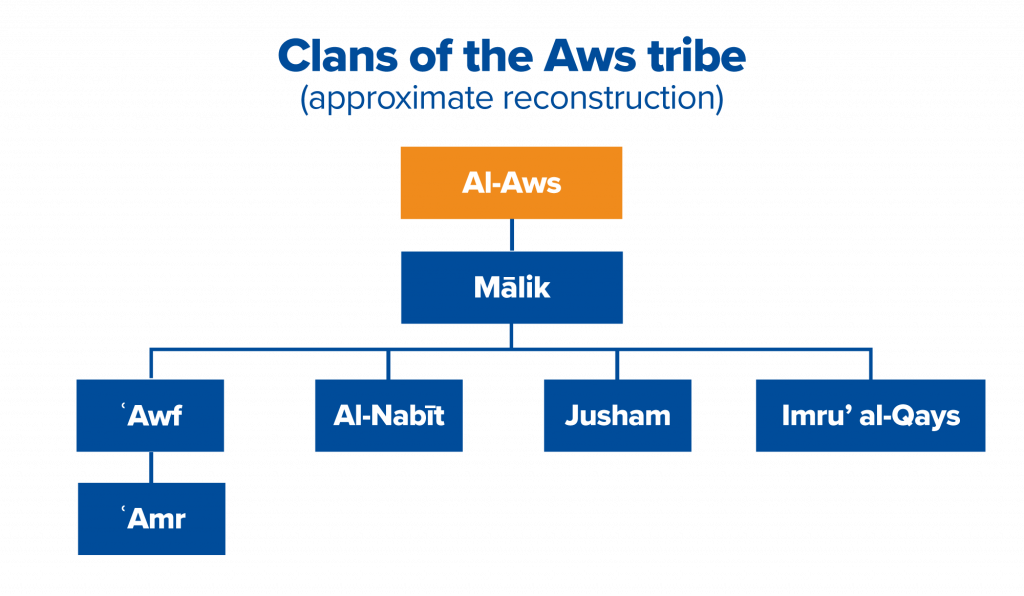

The stipulation in §4 is now repeated word for word for each of the various clans of the Believers and muslims of Yathrib. At this point, they are not called al-Anṣār as they would be later. These Arab clans of Yathrib include from al-Khazraj: (i) Banū ʿAwf, (ii) al-Ḥārith, (iii) Sāʿidah, (iv) Jusham, (v) al-Najjār;

and from al-Aws: (vi) ʿAmr b. ʿAwf, (vii) al-Nabīt, and (viii) al-Aws.

[13]

Whereas all the Emigrants in §3 form one

ʿāqilah group, the Believers of Yathrib continue in the old clan relationships at this time. The phrase

yataʿāqalūn maʿāqilahum al-ūlá (“they shall continue their prior clan arrangements”) is repeated in clauses 4 through 11. The same terms are affirmed for five clans of al-Khazraj and three clans of al-Aws; the Khazraj were both more numerous and slightly earlier in embracing Islam. At the time of this treaty, these clans inevitably included a few remaining

mushriks (polytheists) in their clans; we know this because of the one mention of polytheists in their midst later in the

Kitāb. As the

mushriks are mentioned only once, and even that in passing, we can guess that their numbers must have been negligible. Sources mention that only one major clan of the Aws tribe

[14]> in its entirety refused to embrace Islam (none of its members became Muslim) until quite late, on the occasion of the Battle of Khandaq in 5 AH. This clan, Aws Allāh, as well as others, is not named in the treaty, which suggests that the treaty did not cover all the Arab inhabitants of Yathrib. Most of the rest of the clans of Yathribite Arabs, it would seem, contributed at least some converts.

§12. The Believers shall not neglect to give aid to a debtor (mufraḥ) amongst them according to what is customary in matters of ransom (fidāʾ) or blood money (ʿaql). {And no Believer shall make an alliance with an ally (mawlá) of another Believer to the exclusion of the latter.}

Hamidullah (p. 45) gives the following corroborating hadith from Musnad Aḥmad on the authority of Jābir b. ʿAbd Allāh, “The Messenger of Allah prescribed for each clan its blood money, and then wrote, ‘Verily it is not permitted that a contract of clientage of a Muslim individual should be entered into without the permission of his patron (walī).’”

§13. The God-fearing Believers are against whosoever of them acts wrongfully (baghā) or seeks an act (dasīʿah) of injustice, or promotes sin, transgression, or evil among the Believers. They shall all unite against him even if he is the son of one of them.

Obligations and expectations of aiding in debt, ransom, and other financial obligations that would previously fall to the clan are extended to all Believers here, thus moving the young community toward a conception of solidarity beyond tribe, one in which the ummah becomes a supertribe. As the size of the community swelled beyond a face-to-face community, these obligations took the form of Islamic law that we are familiar with: familial obligations, free and fair commercial exchange, prohibition of usury, obligation of zakāh, and encouragement of charity and debt forgiveness, etc.

§14. A Believer will not kill a Believer [in retaliation] for a non-Believer and will not aid a non-Believer against a Believer.

This stipulation of the

Kitāb is reported in numerous hadith traditions. This clause (viz., §14) has a general meaning, but also addresses an immediate problem. It is aimed at strengthening the ties among the Believers at the expense of their non-believing family members, but also at “stopping the vicious cycle of killings in Medinan society by assuring the participating parties that the old accounts were sealed: every new slaying would be the killing of a fellow Muʾmin for a

kāfir, since those killed before Islam were of course

kuffār.”

[15] In its general sense, the dictum that a Believer cannot be killed in retaliation for a

kāfir is understood in two ways. Whereas most jurists upheld its literal meaning that a Muslim cannot be given a capital punishment in retaliation for a non-believer, the Ḥanafī school, which in fact governed the conduct of the majority of historical Muslim regimes, effectively held that the dictum has a political connotation. This meaning is supported by one narration of the famous hadith in which ʿAlī says that the scroll declares that neither a Believer nor someone with a treaty (

ʿahd) shall be killed [in retaliation] for an infidel (

al-Nasāʾī no. 4760). This addition of “someone with a treaty” is a remarkable addition in al-Nasāʾī’s report, because in most versions it is absent, as in al-Bukhārī, when ʿAlī is asked about the scroll, he says that it has rulings about blood-money, ransom, and that a Muslim shall not be killed for an infidel (

kāfir) (

al-Bukhārī no. 3047). Al-Nasāʾī’s version may lend support to the Ḥanafī view that a Believer and a protected non-believer may not be killed in retaliation for a

ḥarbī, an infidel with whom the community was at war. This disagreement in interpretation is significant in determining the rights of the protected non-Muslims and worthy of a dedicated treatment not attempted here.

[16]§15. The protection (dhimmah) of Allah is one, the least of them [i.e., the Believers] is entitled to grant protection (yujīr) that is binding for all of them. The Believers are each other’s allies (mawālī) to the exclusion of other people.

This clause reiterates what the rest of the document makes clear: affirming the solidarity of the Believers. This is the primary purpose and axis of the first part of the Kitāb that we have labeled the ‘Pact of the Believers.’ This clause adds a crucial dimension, the political equality of all Believers, regardless of their status, expressed as equality in granting protection.

[First mention of the Jews]

§16. The Jews who join us as clients (man tabiʿanā min yahūd) will receive aid and parity [or favor]; they will not be wronged, nor will their enemies be aided against them.

This clause opens the door for the Jews to join the Believers as clients. Note that not only the Jews but also the

mushriks (the polytheists), as noted below, are party to this treaty. This suggests that at least parts of the document were later abrogated, for the polytheists were explicitly excluded with the declaration recorded in Sūrat al-Tawbah (9:1). This clause seems to be an initial accommodation of the Jews who lived among the Arabs of Yathrib; more detailed stipulations are added in the second part of the treaty. The term

tabiʿanā invokes an established tribal practice whereby outsiders settled and joined up with a tribe.

[17]§17. The peace of the Believers is one; no Believer will make peace to the exclusion of another Believer in fighting in the path of Allah. However, [peace must be concluded] on the basis of equality and equity between them.

This clause re-emphasizes that the Believers are a political unity; their war and peace are one. This is clearly a step toward what sociologist Max Weber would call monopoly over violence as the defining feature of a state; Yathrib is being transformed through treaties like this from a spattering of disparate and warring neighborhoods and clans into a city-state—‘the City of the Prophet,’ madīnat al-nabī. The trailing exception seems to allow the possibility of peace concluded by some Believers without the explicit approval of the whole, provided it is not at the expense of any other Believers and does not violate equality and equity among the Believers. Notably, no mention is made here of the Believers in Mecca who have failed to emigrate; the Qur’an explains (e.g., 8:72) that they do not share the political and material advantages afforded by this new alliance, but they shall have the right to receive aid except against a party with whom the Believers of Yathrib have concluded a treaty.

§18. In every expedition made with us the parties take turns with one another.

Clause 18 continues to emphasize equality and fairness among the Believers. Each clan will bear the burden of battle fairly.

§19. {The Believers exact full vengeance for the blood of one another that is shed in the way of Allah.}

Concerning this clause, Serjeant explains, “The whole

ummah confederation is responsible for avenging any of its members killed by parties outside it.” The particular need to emphasize this point is explained by Lecker: “The retaliation for one’s death was usually the duty of his

ʿāqilah. The

Kitāb does not abolish the

ʿāqilah and the

Muʾminūn do not form one

ʿāqilah. But some

Muʾminūn whose

ʿāqilah still included many polytheists needed to be assured that should their blood be shed in the cause of Allāh, full retaliation would be exacted by their fellow

Muʾminūn.”

[18] In other words, even though the pre-Islamic organization is maintained for the time being,

ummatic solidarity is the overriding principle, and the life of a Believer is too important to be left even temporarily to the clan.

§20. The God-fearing Believers guarantee the best and most upright fulfillment of this [treaty] (ʿalá aḥsan hādhā wa-aqwamihi). A mushrik (polytheist) will not grant protection to any property or to any person of the Quraysh, nor will he intervene between them (viz. their property or person) and a Believer.

Another vocalization of the opening clause is:

ʿalá aḥsan hudá wa-aqwamihi, which would mean “The God-fearing Believers are upon the best guidance and most upright guidance,” but this would seem out of place here.

[19] This is the only mention of mushriks, the remaining polytheists within the Medinan tribes, most of whose members had become Believers. This clause indicates a strict and disciplined policy against the Quraysh, and shows that, whereas the Believers are one religious and political party (ummah), the polytheists could not have the same relation to their co-religionists, the Meccan polytheists. This same principle is repeated with respect to the Jews (see below), who are required to support the Prophet ﷺ and his ummah against their own co-religionists, should any of them break this treaty.

§21. When evidence has been established that someone has wrongfully killed a Believer, then he is liable to be killed in retaliation unless the kin (walī) of the murdered is satisfied [with blood money]. All the Believers are united against him and it is not permissible for them not to act against him.

§22. It is not permissible for a Believer who acknowledges what is in this document (ṣaḥīfah) and believes in Allah and the Last Day to support a murderer (muḥdith) or give him shelter. Upon whosoever supports him or gives him shelter is the curse of Allah and His wrath on the Day of Resurrection, and neither repentance nor ransom will be accepted from him.

Some scholars have translated

muḥdith in a general sense as “wrongdoer” or in a literal sense as religious “innovator,” but both are incorrect. Following Ibn Hishām, al-Balādhurī, and other early authorities, Hamidullah and Lecker render it in its proper context as “murderer.”

[20] This clause is, therefore, a continuation of the last one.

§23. Whatever you differ about shall be brought to Allah and Muḥammad.

This clause and the last one closely resemble the verse 4:59: “O Believers, obey Allah and obey the Messenger and those in authority among you, and if you disagree over anything, refer it to Allah and the Messenger, if you should believe in Allah and the Last Day. That is best and most fitting,” which confirms the reports that Sūrat al-Nisāʾ was being revealed about this time, and that this

sūrah provides the proper context for this document as well as commentary on the contemporary events and ethos.

[21] The next verse gives further context, “Have you not seen those who claim to have believed in what was revealed to you, [O Muhammad], and what was revealed before you? They wish to go for judgment to

Ṭāghūt (lit., a false god), while they were commanded to reject it; and Satan wishes to lead them far astray (4:60).” Exegetes agree that this was revealed when some Yathribite converts, hereby revealed as hypocrites, sought a Jewish leader for a prejudiced judgment, fearing the Prophet’s fair judgment, in a dispute with his Jewish neighbor. Some reports mention that this challenger to the Prophet’s authority was Kaʿb b. al-Ashraf, whom we shall meet again presently.

[The Truce with the Jews]

§24. The Jews bear expenses along with the Believers so long as they continue at war.

We shall discuss below the question of when this truce with the Jews was concluded, and how it relates to the Pact of the Believers above. At a later stage in Medinan life, the non-Muslims will be incorporated into a centralized political entity through a treaty of peace and protection (dhimmah) and poll tax (jizyah), one built on the Believers’ role as the providers of security and hence their military domination. This treaty, however, does not assume a central government yet, and allows the Jews to enter a deal whereby they did not pay a poll tax but rather spent on a joint defense. It may be noteworthy that when addressing the Jews, the armed conflict is referred to as war (ḥarb) whereas in the first part of the document (i.e., the treaty among the Believers), it is called jihād in God’s path.

§25. The Jews of Banū ʿAwf are {a community alongside}/<a community from>/[secure from] the Believers; the Jews have their religion (dīn) and the Muslims have theirs. This applies to their clients (mawālīhim) and themselves. But whoever does wrong or commits treachery brings evil only on himself and his household.

This is a much-debated clause. Due perhaps to scribal error or the underdeterminacy of the Arabic script at the time, four variants of this clause are preserved. The standard version is Ibn Isḥāq’s:

ummah maʿa al-muʾminīn:

one community with the Believers. Abū ʿUbayd’s version:

ummah min al-muʾminīn: one community from among the Believers. At least two other variants exist. One is:

amanah min al-muʾminīn: secure from the believers, and finally, a different reading of Ibn Isḥāq:

lil-yahūd banī ʿawf dhimmah min al-muʾminīn: the Jews have the

dhimmah protection from/by the Believers.

[22] The next clause goes on to specify that the Jews and the Muslims will have their separate religions.

Of all these variants, AU’s is the least likely, and its meaning is misleading, as it contradicts nearly every other clause of the document, including the very next one.

[23] Since the very first two clauses of the document define the

ummah as consisting of the Believers (and

muslims) to the exclusion of all others, joined by faith and struggle (

jihād) for it, and then the rest of the document goes on to detail the relationship of two distinct groups, the Believers and the Jews, accepting this reading renders the document illogical. We read, for instance, that “The Jews will bear the expenses with the Believers so long as they are at war” (§24, 38), and that the Jews, if called to some agreement by the Believers, should accept, and vice versa (§45). In all these cases, the Jews are a group distinct from the Believers not only in religion but also in political identity and status, some crucial reciprocal rights stated here notwithstanding. Lecker makes a strong case that the best reading is the last one,

amanah min al-muʾminīn (Lecker, 141-147).

§26-30. [The clause in §28 for the Jews of Banū ʿAwf is extended to the Jews of Banū al-Najjār, Banū al-Ḥārith, Banū Sāʿidah, Banū Jusham, and Banū al-Aws.]

§31. {The Jews of Banū Thaʿlabah have the same terms as the Jews of Banū ʿAwf.} But whoever does wrong or commits treachery brings evil only on himself and his household.

§32. {The Jafnah are a clan (

baṭn[24] of Thaʿlabah and are on a par with them.

§33. The Banū al-Shuṭaybah have the same rights as the Jews of Banū ʿAwf. Righteousness is easier than sin.

[25] §34. The allies of the Thaʿlabah are on a par with them.

§35. The nomadic allies (biṭānah) of the Jews are on a par with them.}

Clauses §31 (first part) and §32-35 are, as indicated, found only in Ibn Isḥāq’s version, but Abū ʿUbayd’s version adds at a later point in the document that the Banū al-Shaṭbah are a baṭn from Jafnah. Read together, and assuming that baṭn means a subgroup in a tribe, it means that the Banū al-Shaṭbah are a subtribe of Jafnah, and Jafnah a subtribe of Banū Thaʿlabah. Since the Thaʿlaba were situated on the eastern outskirts of Medina, they were added later to the treaty. The term biṭānah, which generally means outsiders that are intimate with a group (e.g., 3:118), here refers to the Jews’ nomadic allies (Lecker, 150, 153; Hamidullah also agrees with this).

§36. None of them [viz. the Jews] may leave without Muḥammad’s consent. {There is no refraining from retaliation for a wound. He who sheds blood (fataka) brings it upon himself and his household, except he who has been wronged, and Allah demands the most righteous fulfillment of this [treaty].}

Yakhruj literally means leave or exit. Hamidullah takes this to mean leave on a military expedition, whereas Lecker argues that it means to leave, as in move out and relocate; the latter is more likely.

§37. {The Jews have their expenditure, and the Muslims theirs.} The [parties to this treaty] will aid each other against whosoever is at war with the people of this document. Between them is good will and sincerity. And righteousness is easier than sin.

[26] A man will not act unjustly toward his client (

ḥalīf), and anyone wronged will be helped.

§38. The Jews bear expenses along with the Believers so long as they continue at war. [Repetition of §24.]

§39. The valley of Yathrib <Medina> is a ḥarām (sanctuary) <ḥaram> for the parties to this document.

§40. {The protected neighbor (jār) is like one’s self so long as he does not harm or act treacherously.

§41. No protection may be granted without the permission of the parties to this [document].}

§42. Whenever there is a murder {or dispute} between the people of this document from which evil is feared, the matter is to be referred to Allah and Muḥammad {the Messenger of God, may the peace and blessings be upon him}. Allah demands the most pious and righteous fulfillment of this document.

Contrast this clause (only those great crimes that could lead to civil war are to be referred to the Prophet) to §23 in the Believers’ Pact (all differences shall be referred to the Prophet).

§43. {No protection will be granted to the Quraysh nor to whoever supports them.

§44. They [viz. the parties to this treaty] undertake to aid each other against whosoever attacks Yathrib.}

This prohibition of any deal with the Quraysh highlights an important feature of this document. The Jews or mushriks who sought to make a deal with the Meccans instead of the Prophet could not do so. In other words, their freedom was limited, as they were barred from making a deal with their own co-religionists or the religion of their choice.

§45. {If they [the Jews] are called to an agreement, they will accept it, and if they call for the same, it is incumbent upon the Believers to accept it,} <If they ask the Jews to make peace with any ally of theirs, they shall make peace with him, and if they ask us for a similar thing, the same shall be incumbent upon the Believers,> except if someone makes war on account of religion [ḥārabah fī al-dīn]. Every group is responsible for the part that faces them.

The Jews could not aid the Meccans against the Believers, but nor could the Believers aid anyone seeking to wage war against the Jews. This principle becomes enshrined in Islamic law in the form of the dhimmah contract later.

§46. The Jews of al-Aws, their allies and their persons, have the same standing as the parties to this document, with the truest fulfillment with regard to the parties to this document. Verily, righteousness is easier than sin, and he who violates it does so only against himself. Allah demands the truest and most righteous fulfillment of what is in this document.

This is the second time the Jews of al-Aws are mentioned (assuming that the reference to the Jews of Banū al-Aws in §30 refers to the same group). If by “the Jews of al-Aws'' is meant Banū Qurayẓa, which is a strong likelihood (see analysis below), we may conclude from this repetition that they were added to the treaty twice. One possibility is that they were initially added along with the rest of the Jews living among the Arab neighborhoods, and after they violated or intended to violate it by siding with the Quraysh during or after Badr, they were forgiven and once again added. Note that both of the Jewish tribes of Banū Qaynuqāʿ and Banū al-Naḍīr had already been expelled at this point.

§47. This Kitāb will not intervene to protect an unjust man or a violator of pledge. He who goes out is secure and who stays {in Medina} is safe, except he who acts unjustly or in violation of the pledge. {Allah is the Protector of him who is righteous and God-fearing, and so is Muḥammad, the Messenger of God.} <The most fitting to be the parties to this document are those who are righteous and benevolent.>