[1] The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University recently noted that anti-Muslim hate crimes rose 89% in 2016 from the previous year, as discussed in Brian Levin, “Hate Crime in U.S. Survey Up 6 Percent; But Anti-Muslim Rise 89 Percent, NYC Up 24 Percent So Far in 2016,”

HuffPost, October 22, 2016, updated December 6, 2017,

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/brian-levin-jd/hate-crime-in-us-survey-u_b_12600232.html.

[6] Alan Kramer,

Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 251.

[8] Peter Watson, “The Bolshevik Crusade for Scientific Atheism,” in

The Age of Atheists: How We Have Sought to Live Since the Death of God (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014). He cites as a source Paul Froese,

The Plot to Kill God: Findings from the Soviet Experiment in Secularization (Berkley: University of California Press, 2008).

[9] R. J. Rummel,

Death by Government (Rutgers, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1994).

[11] The susceptibility of such boundaries to conflict has also been subject to research; for instance, Francesco Caselli and Wilbur John Coleman offer a model for violence and “ethnic distance,” which they define broadly to include the cumulative effect of “physical, religious, linguistic, and other cultural differences.” F. Caselli and W. J. Coleman, “On the Theory of Ethnic Conflict,”

Journal of the European Economic Association 11 (2013): 161–92.

[12] For a discussion on the relevance of religion and language to intragroup cohesion, see Oromiya-Jalata Deffa, “The Impact of Homogeneity on Intra-Group Cohesion: A Macro-Level Comparison of Minority Communities in a Western Diaspora,”

Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37, no. 4 (2016).

[16] This fallacy was also evident in a much-publicized 2015 article in

The Atlantic entitled “What ISIS Really Wants,” wherein author Graeme Wood included the vacuous statement, “The reality is that the Islamic State is Islamic. Very Islamic.” This, of course, means absolutely nothing without specifying whether we are using a definition of Islam according to the terrorists or according to mainstream Muslims. The article attempted to substantiate this bizarre assertion using sporadic scriptural citations with no reference to the normative exegesis of those same passages from reputable authorities within the mainstream Muslim community. In fact, the main academic reference for the article, Princeton professor Bernard Haykel, conceded in a

February 2015 CNN interview, “I’m not a judge as to whether ISIS is a perversion or not [of Islam] . . . you have to be a Muslim and a Muslim jurist to judge that.” Of course, this crucial point never made it into Wood’s article, much less any mention of the Muslim jurists, imams, and leaders globally who have declared ISIS to be completely un-Islamic. Curiously, Wood’s article demonstrated a greater interest in differentiating the doctrines of ISIS from al-Qaeda than it did in differentiating either group from mainstream Islam.

[17] Sunan Abī Dāwūd, no.

4941

, Jāmi al-Tirmidhī, no.

1924.

[18] Musannaf Ibn Abi Shaybah, no. 10491.

[19] Sahih Bukhari, no. 6862.

[20] Saïd Amir Arjomand, “The Constitution of Medina: A Sociolegal Interpretation of Muhammad’s Acts of Foundation of the ‘Umma,’”

International Journal of Middle East Studies 41, no. 4 (2009): 555–75.

[21] Said ibn al-Musayyib narrated that the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ used to regularly donate money as charity to a Jewish household, a practice that was continued by the Muslim community long after the Prophet ﷺ passed away. Abu Ubayd al-Qasim ibn Sallam (d. 224 AH),

Kitab al-amwal (Cairo: Dar al-Shuruq, 1989), 727–28.

[22] Ibn Kathir,

al-Bidayah wal-nihayah, (Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyah, 1987), 3:56.

[25] See the discussion under “When Muslim Men and Women Express a Desire for Sharia, What Do They Mean?” in John L. Esposito and Dalia Mogahed,

Who Speaks for Islam (Omaha: Gallup Press, 2008), 52–63, wherein they elucidate why this point is crucial for interpreting any data about Muslim attitudes.

[26] Abu Ishaq al-Shatibi (d. 790 AH),

al-Muwafaqat (Cairo: Dar Ibn Affan, 1997), 1:38.

[27] Muṣṭafá al-Zarqāʾ,

al-Madkhal al-fiqhī al-ʿām (Damascus: Dar al-Qalam, 2004), 1:153.

[28] This is a major topic in Islamic jurisprudence, known as

taghayyur al-fatwa bi-taghayyur al-zaman (the changing of religious edicts with the changing of times). For instance, al-Sarakhsi (d. 483 AH) frequently notes the changes in Abu Hanifah’s (d.150 AH) jurisprudence by his students Abu Yusuf (d.182 AH) and Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Shaybani (d.189 AH), arising not due to disagreement over sacred texts but simply because of the changing circumstances of society with time. See, for example, al-Sarakhsī,

al-Mabsūṭ (Beirut: Dar al-Ma’rifah, 1993), 8:178; Ibn Ābidīn,

Radd al-muḥtār, (Beirut: DKI, 1971), 1:166; al-Rafi’i,

Taqrīrāt al-Rāfī’ī ‘alà hashiyat Ibn `Ābidīn (Beirut: DKI, 2003), 1:16; Al-Qaraḍāwi, Yusuf.

Min Fiqh al-Dawla fil-Islām (Cairo: Dar al-Shorouq 2001) 2-3. If so many of the rulings related to societal issues (

mu’āmalāt) changed in one generation, there is an even greater need to reevaluate and contextualize rulings in the postindustrial age. For more information on the concept of change in Islamic rulings, refer to Nazir Khan, “Difference of Opinion: Where Do We Draw the Line?,”

Yaqeen, December 10, 2019,

https://yaqeeninstitute.org/nazir-khan/difference-of-opinion-where-do-we-draw-the-line/.

[29] Ibn al-Qayyim,

Iʿlām al-muwaqqiʿīn (Dammam: Dar Ibn al-Jawzi 2002), 4:337.

[30] The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics, and Society, The Pew Research Center, April 30, 2013.

[31] See, for example, al-Sarakhsī (d. 490 AH), Burhān al-Dīn al-Ḥanafī (d. 616 AH), Ibn al-Sa’ātī (d. 694 AH), Abu’l-Barakāt al-Nasafī (d. 710 AH). Ibn al-Humām (d. 861 AH) explicitly explains the reasoning to relate to the capacity to fight against Muslims. Ibn al-Humām,

Fatḥ al-Qadīr (Beirut: DKI 2002), 6:68. This understanding is also substantiated by other Prophetic narrations on the matter, which state that the punishment applies to the person who breaks off from and opposes the community—

al-mufariqu li’l-jama’ah (

Sahih Muslim, no. 1676). For a more detailed presentation of this perspective refer to Abd al-Muta’āl al-Sa’īdī,

al-Hurriyah al-dīniyyah fi al-Islām (Alexandria: Maktabah al-Iskandariya, 2011). See also Jonathan Brown, “The Issue of Apostasy in Islam,”

Yaqeen, July 5, 2017,

https://yaqeeninstitute.org/jonathan-brown/the-issue-of-apostasy-in-islam/.

[32] The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ established an agreement with the Meccans called the treaty of Hudaybiyyah, in which one of the articles explicitly permitted a Muslim who left the faith to be able to return to the Meccans.

[33] The numbers from the Pew poll are accurately cited here with confirmation from James Bell of the research center itself: “A Fact-Check of Bill Maher and His Critics: A Closer Look at Pew's (2013) Survey Report (Part 1),”

Empethop, February 2, 2015,

http://empethop.blogspot.ca/2015/02/a-fact-check-of-bill-maher-and-his.html. This blogger’s personal commentary and attempted interpretations, however, seem poorly informed with respect to the underlying dynamics in Muslim society.

[34] As discussed in Esposito and Mogahed,

Who Speaks for Islam, 73–74.

[35] An overview of some of the diverse perspectives and debates on this topic can be found in R. H. A. AlSoufi, “Strategies for the Justifications of

Hudud Allah and Their Punishments in the Islamic Tradition” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2012).

[36] Abd al-Aziz al-Fawzan, “Daḥḍ al-shubuhāt tuthār ḥawl al-'uqubāt al-shar'īyyah,”

Majallah al-Bayan (al-Muntada al-Islami) 18, no. 193 (Ramadan 1424/November 2003): 16. See also Ibn Uthaymīn,

Sharḥ al-Mumti’ (Dammam: Dar ibn al-Jawzi 2007), 14:256-257.

[37] On deterrence (

zajr) as an objective, this is an overarching philosophy of the penal system and applies to different scenarios; it is also mentioned in another context by al-Kāsānī,

Badā’ī al-sanā’ī (Beirut: DKI 2003): 9:248.

[38] See

Jami’ al-Tirmidhi, no. 1424 and

Sunan Ibn Majah, no. 2642. This is also considered a foundational principle in modern law, known as Blackstone’s formulation, after the English jurist Sir William Blackstone (d. 1780 CE), who articulated it in his

Commentaries on the Laws of England (1760).

[39] In an appearance on Bill Maher’s HBO show in 2014, the anti-Muslim polemicist Sam Harris stated that peaceful Muslims are “nominal Muslims who don’t take their faith seriously.’’ In other words according to him, Muslims who aren’t violent are fake Muslims who aren’t actually practicing the tenets of their faith.

[40] Chase Robinson, a professor of Islamic history, writes, “Here it bears emphasizing that Islamists are not ‘literalist’ in the sense that they cleave to the explicit or self-evident meaning of texts, such as the Qur’an or Prophetic traditions. Instead, they privilege those proof-texts that conform to their ideological presuppositions, ignoring or explaining away those that do not.” Chase Robinson,

Islamic Civilization in Thirty Lives: The First 1,000 Years (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016), 211.

[41] Osama Bin Laden, interview by Tayseer Alouni, Al Jazeera, October 21, 2001.

[42] ISIS also famously used this perverse logic of revenge as justification for the killing of American journalist Steven Sotloff. In their fourth issue of

Dabiq, they wrote, “his killing was in consequence of US arrogance and transgression which all US citizens are responsible for as they are represented by the government they have elected, approved of, and supported, through votes, polls, and taxes.” Cited in Lizzie Dearden, “Isis Publishes ‘Letter’ from Steven Sotloff to Family in Propaganda Magazine,”

Independent, October 14, 2014,

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/isis-publishes-letter-from-steven-sotloff-to-family-in-propaganda-magazine-9794613.html. Sotloff’s mother had a better understanding of Islam when she quoted the Qur’anic verse, “No soul is responsible for the sins of another.” The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ abolished this practice of revenge killings immediately after he took control of Mecca, and he began by negating his own clan’s claim to revenge in the death of the son of his cousin Rabi’ah ibn al-Harith.

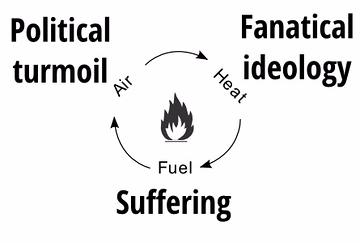

[43] These three factors tend to be discussed in different bodies of literature given the highly compartmentalized nature of modern academia, with sociologists focusing on environmental factors and social injustices which mobilize populations, political scientists focusing on the influence of ideologues in structuring a political movement, and psychologists focusing on the impact of social isolation, alienation, and complex trauma. The reality of the matter is that all of these factors are relevant to the discussion, and an integrated approach is necessary.

[44] Toby Craig Jones, “America, Oil, and War,”

Middle East Journal of American History 99 (2012): 208–18.

[45] Richard Garfield,

Morbidity and Mortality Among Iraqi Children from 1990 Through 1998: Assessing the Impact of the Gulf War and Economic Sanctions (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame, Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, 1999).

[46] Gilbert Burnham, Riyadh Lafta, Shannon Doocy, and Les Roberts, “Mortality After the 2003 Invasion of Iraq: A Cross-Sectional Cluster Sample Survey,”

The Lancet 368, no. 9545 (2006): 1421–28.

[50] Truls HallbergTønnessen, “Heirs of Zarqawi or Saddam? The Relationship Between al-Qaeda in Iraq and the Islamic State,”

Perspectives On Terrorism 9, no. 4 (August 2015).

[52] Anthropologist Gabriel Marranci outlines the following three theses that are typically encountered in the academic debate about the emergence of violent movements: “Islam, as religion, is more prone to violence and fundamentalism (Bruce 2000); fundamentalists are Muslims with political aims who manipulate Islam for their own ideological purposes (Esposito 2002, Hafez 2003, Milton-Edwards 2005); and finally, the representation of Islamic fundamentalism as a historical process was started by charismatic Islamic ideologues (such as Mawdudi, Al-Banna, and Qutb).” Gabriel Marranci,

Understanding Muslim Identity—Rethinking Fundamentalism (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 21.

[54] Milton-Edwards offers a perspective on how this tension has shaped many of the modern movements in her book,

Islamic Fundamentalism Since 1945 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2005).

[55] For instance, Sayyid Qutb’s explanation of the term

jahiliyyah (un-Islamic ignorance) as “the rule of people by other people” is sometimes used to support the notion that Islam is antithetical to other civilizations and cannot coexist with non-Islamic governments. William Shepard, “Sayyid Qutb’s Doctrine of

Jahiliyya,”

International Journal of Middle East Studies 35, no. 4 (2003), 521–45. While terrorists are keen to exploit such ideas, others argue that Qutb’s writings must be understood in the context of opposing a repressive regime and point to his advocacy of human rights which terrorists ignore; Sayyid Qutb wrote,

“Forced religious conversion is the worst violation of a most inviolable human right . . . freedom of belief is man’s most precious right in this world and ought to be cherished and protected.”

In the Shade of the Qur’an (

Fi Zilal al-Quran) (Markfield: The Islamic Foundation, 2003), 1:212. Adil Salahi, Qutb’s translator, comments on the extremist use of Qutb’s writings: “It may be said, perhaps with some justification, that Sayyid Qutb was a bit too strong in his argument, providing a platform for extremism to stand on. Here we find ourselves trying to answer the question: to what extent may a writer be blamed for being misunderstood by his readers? In the case of Sayyid Qutb, the overwhelming majority of his readers maintain that he reflects the middle path Islam adopts” (vol. 7, xii) and “terrorism was as hateful to [Sayyid Qutb] as it was to any fair-minded person who values justice and freedom as basic human rights” (vol. 8, xv).

[56] Christopher M. Blanchard, “Al Qaeda: Statements and Evolving Ideology,” CRS Report for Congress RL32759 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, July 9, 2007), 3,

www.fas.org/sgp/crs/terror/RL32759.pdf.

[58] Ibn al-Qayyim (d. 751 AH) writes, “The purpose of religious law is the establishment of justice amongst people, so whichever method leads to upholding justice and fairness is considered to be part of the religion’s teachings, and not contradictory to it.” Abbreviated from a larger selection of quotes cited in Muhammad Ammarah,

Ma’rikah al-mustalahat bayna al-gharb wal-Islam (Cairo: Nahdah Misr, 2004), 179.

[59] Imam Abu Hanifah (d. 150 AH): “The purpose (

maqsūd) of calling a certain land ‘Land of Islam’ or ‘Land of disbelief (

kufr),’ is not about Islam or

kufr. It is about security versus fear.” He goes on to explain that the former is a land that offers Muslims and non-Muslims under its covenant (

Dhimmīs) safety and security, while the latter leaves Muslims in a state of fear. See Al-Kasānī,

Badā’ī al-sanā’ī (Beirut: DKI 2003), 9:573.

[60] For a concise overview, see the discussion on this topic in Ahmad al-Raysuni,

Fiqh al-thawrah (Cairo: Dar al-Kalimah, 2013), 22–27.

[61] For a perspective outlining the error of this negative reductionistic attitude in detail refer to Abdullah al-Ṭarīqī,

al-Ta’āmul ma’a ghayr al-Muslimīn: usūl mu’āmalatihim wa isti’mālihim: Dirāsah fiqhīyyah (Riyadh: Dar al-Fadilah, 2007), 90–95, 143.

[62] Saḥīḥ Ibn Hibban, no. 4969.

[63] Ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥakam,

Futūḥ Miṣr, vol. 1 (Cairo: Maktabah al-Thaqafah al-Deeniyah, 2010), 195.

[65] Saḥīḥ Bukhārī, no. 6103.

[66] Musnad Aḥmad, no 23958.

[67] See also Justin Parrott,

Jihad in Islam: Just-War Theory in the Quran and Sunnah,

Yaqeen, May 15, 2020. https://yaqeeninstitute.org/justin-parrott/jihad-as-defense-just-war-theory-in-the-quran-and-sunnah/

[68] In order to substantiate this notion, recourse is often made to the works of classical jurists who lived in times of imperial conquest and advocated a continuous “expansionist” policy against hostile political forces. However, as Professor Sherman Jackson demonstrates, the central concern of such jurists, like Ibn Rushd (d. 595 AH) and others, was actually the security of Muslim lands living under the constant threat of foreign invasion. Sherman A. Jackson, “Jihad and the Modern World,”

Journal of Islamic Law and Culture 7, no. 1 (2002), 17. On the other hand, extremist movements jeopardize the safety of all humanity and engage in senseless bloodshed, and therefore, their methods are completely antithetical to the teachings of Islam.

[69] The Prophet Muhammad himself personally freed sixty-three slaves during his life, his wife Aisha freed sixty-nine slaves, and his companions freed numerous slaves, most notably his companion ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAwf who freed an astounding thirty-thousand. For more information on how Islamic teachings dealt with slavery, refer to Nazir Khan, “Divine Duty: Islam and Social Justice,”

Yaqeen, February 4, 2020,

https://yaqeeninstitute.org/nazir-khan/divine-duty-islam-and-social-justice/.

[70] Saḥīḥ Bukhārī no. 2227.

[71] Ibn Hajar al-`Asqalani (d. 852 AH) in

Fatḥ al-Bārī sharḥ Saḥīḥ al-Bukhārī (Beirut: al-Risalah al-Alamiyyah 2013), 1:262. See also the alternate view in al-Qastallani’s

Irshād al-sārī and al-Kashmiri’s

Fayḍ al-Bārī that it is a linguistic device referring to the general reversal of affairs.

[72] Al-Tabarānī,

Muʿjam al-awsaṭ, no. 5787.