A Punishment or a Mercy? What We Can Learn from the Coronavirus

April 14, 2020

Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research.

For more on this topic, see Faith in the Time of Coronavirus

Introduction

“Is the coronavirus a punishment from Allah?” “Is Allah angry at us?” “Is the coronavirus a blessing, test, or punishment?” These theological questions are in the hearts and minds of many Muslims since the coronavirus spread worldwide, infecting over two million and taking the life of over 100,000 people thus far.[1] Answering these questions requires a discussion of core theological concepts, including a thorough understanding of the concept of punishment. In this paper, we seek to answer these questions, describe what American Muslims actually report believing about the topic, and provide practical solutions to the questions.

The concept of punishment

Punishment is the imposition of an undesirable outcome upon a group or individual in response to an offense.[2] The motivation behind punishment and its manifestations vary substantially. From an Islamic theological perspective, the word punishment is used to denote various types of trials, rebukes, reprimands, penalties, and disciplinary actions that may be manifested in this life or the afterlife. Regarding the afterlife, the hellfire is mentioned as the most serious punishment. This form of punishment only occurs after one has been taken to account by Allah on the Day of Judgment, with His infinite justice and mercy.[3] Punishment in the afterlife is not singular, but varies in severity and duration depending on the extent of one’s injustice against oneself and others.[4] Similarly, rewards in the afterlife also vary based on the extent of one’s righteousness. The believer should always be cognizant of both rewards and punishments, as they motivate righteous conduct and discourage behavior that is unbefitting of a believer. Ibn al-Qayyim elaborated, “The Hellfire was created to frighten the believers and to purify the sinners and criminals. It serves as a means of purification from the filth that the soul contracted in this world. Had it purified itself here through genuine repentance, good deeds which erase [sins], and calamities which atone [for sins], it would not have needed to be purified there.”[5]

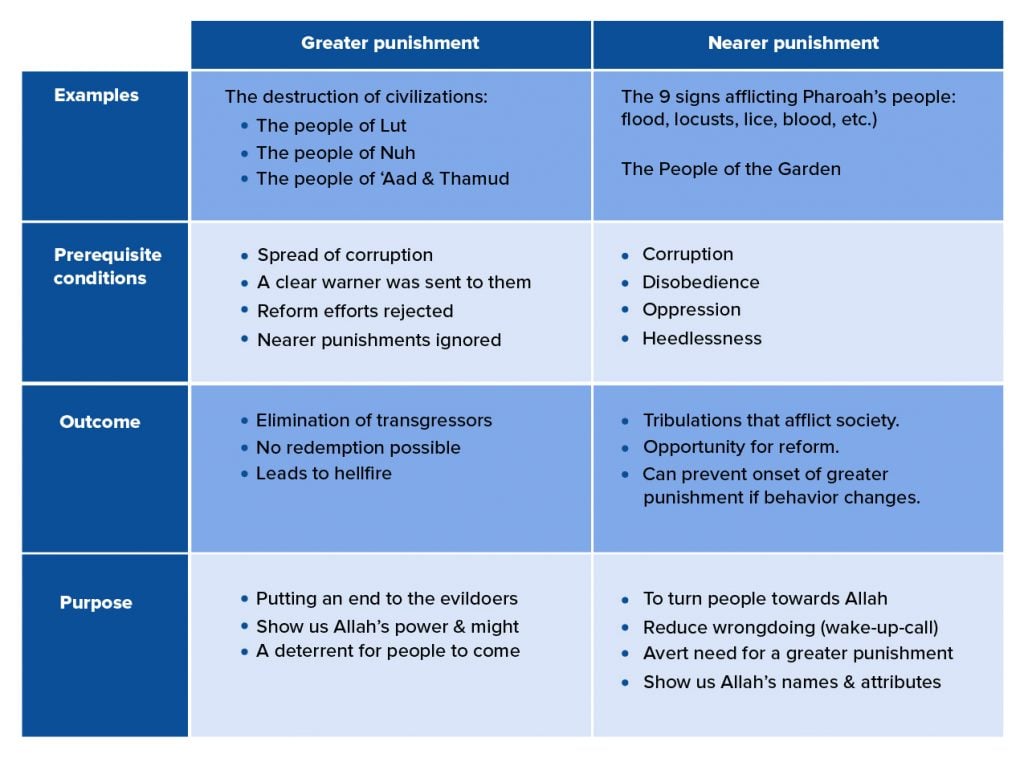

As for punishments in this life, the Qur’an separates them into two types. The first type is a retributive punishment that constitutes a decisive judgment from Allah, one that includes no path to redemption. Allah says, “Rather, it will come to them unexpectedly and bewilder them, and they will not be able to repel it, nor will they be reprieved.”[6] The intent behind retributive punishment includes ending oppression, supporting a prophet, demonstrating Allah’s attributes of majesty towards a nation that rebelled against their prophet, and teaching future generations. This type of punishment has a number of conditions before Allah executes it, including the sending of a prophet, the society's rejection of the prophet, persistence in corruption, and the rejection of multiple warnings. Allah mentions retributive punishment being executed in various ways that destroyed prior rebelling nations, “So each [nation] We seized for their sin; and among them were those upon whom We sent a storm of stones, and among them were those who were seized by the blast [from the sky], and among them were those whom We caused the earth to swallow, and among them were those whom We drowned. And Allah would not have wronged them, but it was they who were wronging themselves.”[7]

The second type of punishment in this life is not meant to be a decisive judgment, but a deterrent that aims to bring people back to Allah and to reform society. Allah mentions this type of punishment in the Qur’an immediately after mentioning the punishment of hellfire.

وَلَنُذِيقَنَّهُم مِّنَ الْعَذَابِ الْأَدْنَىٰ دُونَ الْعَذَابِ الْأَ كْبَرِ لَعَلَّهُمْ يَرْجِعُونَ

“And We will surely let them taste the nearer (الأدنى) punishment short of the greater (الأكبر) punishment so that perhaps they will return.”[8] Numerous companions of the Prophet ﷺ and early scholars have interpreted the “nearer punishment” as the difficulties, ailments, and general tribulations of this life that Allah subjects His servants to with the purpose of encouraging them to repent and turn back to Him.[9] Thus, the intention of the “nearer punishment” is to literally bring people nearer to Allah. In another verse that reiterates Allah’s justification in permitting worldly tribulations, He mentions, “Corruption has appeared throughout the land and sea because of what the hands of people have earned, so He may let them taste some of the consequences of what they have done so that perhaps they will return.”[10] Once again, we see the intent of Allah in allowing people to taste difficulties is to cause them to turn to Allah. Therefore, the various afflictions that constitute “the nearer punishments” in this life should be seen as compassionate reprimands from Allah for the betterment of humanity.

Although it may seem counterintuitive that punishments can arise from compassion, recent research on compassion suggests this may be the case based on intentions. When the intention of the punishment is to alleviate the suffering of others and increase societal harmony, this may be considered compassionate or altruistic punishment. This may include providing negative feedback to the wrongdoer so that they change their behavior in the future, although the punisher does not benefit.[11] Therefore, we need to rethink our understanding of punishment, especially when it comes from the One who is more merciful to us than our own mothers.[12] These compassionate reprimands are akin to treating a patient with bitter medication that, despite being undesirable and possibly painful, may be necessary to achieve health and well-being. Ibn al-Qayyim put this analogy beautifully when discussing compassionate punishments, “The wisdom of Allah necessitated that He appoint an appropriate remedy for every disease, and remedying the misguided requires the most difficult remedies [to endure]. A compassionate doctor may cauterize the sick person, searing him with fire over and over again, in order to remove from him the foul elements that sabotaged his natural state of health. And if [this doctor] sees that amputating the limb is better for the sick person, he severs it, causing him by that the most severe pain.”[13]

Psychology has discussed the role of reward and punishment in behavior modification. The theory of operant conditioning in behaviorism suggests that both reinforcements and punishments may influence behavior.[14] From an Islamic standpoint, positive reinforcements include offering rewards for righteous conduct, including generous giving of ḥasanāt (good deeds) and attaining the pleasure of Allah. Similarly, negative reinforcements include removing sayyiʾāt (bad deeds) to encourage righteous conduct.[15] Both types of reinforcements may be simultaneously given as there are individual differences in what motivates behavior.[16] However, in the situation where people are neither intrinsically motivated by their love of Allah nor extrinsically motivated through reinforcements, positive and negative punishments can be used to make undesirable behaviors less likely to continue or reoccur. Positive punishments involve adding undesirable consequences in order to discourage behaviors, whereas negative punishments involve removing something pleasant to discourage behaviors. From the Islamic standpoint, positive punishment may include the introduction of tribulations to a society to decrease unjust human behavior or negative punishment such as the loss of life and wealth. The purpose of both types is to bring people back to Allah. The concept of influencing behavior through blessings and hardships is clearly articulated in the verse, “...And We tested them with good and bad so that perhaps they would return.”[17]

A profound example of compassionate punishment can be found in the story of the people of the garden (aṣḥāb al-jannah) in Sūrat al-Qalam. Despite full awareness of the precedent set before them to share a portion of the garden’s harvest with the poor, they conspired to deny the poor their share the night before. Then, in the early hours preceding the harvest, they agreed with one another to deny any needy person access to the garden. When they reached the garden in the morning, they saw that Allah had punished them by completely destroying their garden during the night. After initially blaming each other, they collectively took responsibility, acknowledged their mistake, and sought Allah’s forgiveness saying, “Perhaps our Lord will exchange for us something better than it. Indeed, we are toward our Lord desirous.”[18] This story beautifully illustrates how compassionate reprimand, which Allah explicitly mentioned as both a test and a punishment, can be a mercy to people. Had Allah not subjected them to this “nearer punishment,” they may have never turned sincerely to Allah and may have been held accountable for their crime in the afterlife.

Table 1. Differences Between Greater and Nearer Punishments

Benefits vary at the individual level

The great scholar of Islam, al-ʿIzz ibn ʿAbd al-Salām, said, “In tribulations, trials, misfortunes, and calamities lie a number of benefits; these benefits have differing degrees of relevance, differing in accordance to the various ranks of people.”[19]

Compassionate reprimands at the societal level and other types of afflictions[20] can end up being either blessings or further punishment at the individual level. The benefits or harms achieved are proportionate to the attitude and behavior of each person. Those who feel pain during a test but endure it with patience may have their sins expiated.[21] Those who are content with Allah's divine decree may be elevated in rank. The “nearer punishment” only becomes a further punishment for those who object to Allah’s decree and engage in displeasing behavior.

A cautionary note about qadar (fate)

Although the Islamic sources confirm that afflictions, including plague-like epidemics, may constitute “nearer punishments” from Allah, it is beyond human perception to pinpoint the exact causes behind specific afflictions. It is pure conjecture and speculation for anyone to claim that the coronavirus is a punishment to a specific nation (e.g., China) or for a specific reason. The fact that the coronavirus is a global pandemic means that it is not an affliction to any particular nation. Allah warns us about speaking on His behalf without knowledge, saying, “Or do you speak about Allah that which you do not know?”[22]

So is the coronavirus a punishment?

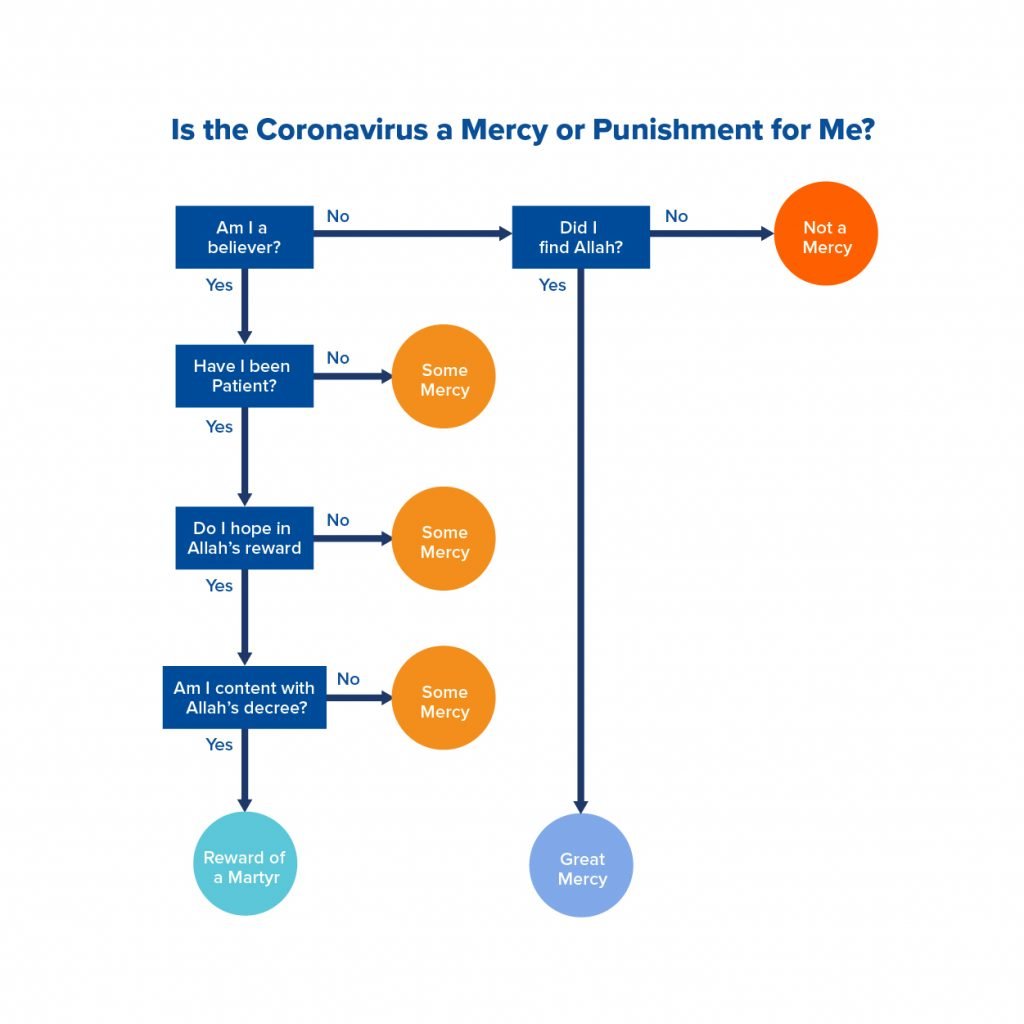

The closest precedent to this question may be when ʿĀishah, the wife of the Prophet ﷺ, asked him about the plague. He responded, “It is a punishment that Allah sends upon whomever He wills, but Allah has made it a mercy for the believers. Any servant who resides in a land afflicted by plague, remaining patient and hoping for reward from Allah, knowing that nothing will befall him except what Allah has decreed, will be given the reward of a martyr.”[23] Although the coronavirus is not technically the plague, they share in being infectious diseases with painful symptoms that may be fatal. Therefore, it is reasonable to use the Prophet’s explanation about the plague to understand the coronavirus. What does the Prophet’s answer teach us? First, we learn that the plague can be a punishment or a mercy. In light of our previous conversation, it may be considered a compassionate reprimand intended to return people to the path of righteousness. This is supported by Ibn Ḥajar, who explains that the punishment mentioned in the aforementioned hadith has been expedited in this world before the afterlife. He argues that the plague is the direct result of widespread moral corruption in society.[24] However, at both the societal and individual level, it may end up being a further punishment or a mercy. How can this be? When the Prophet ﷺ clarified that Allah made it a mercy for the believer, the plague becomes an individual punishment conditional on one not having īmān or responding inappropriately. Thus, the coronavirus (or the plague) may be a great mercy and blessing for the believer who exercises patience, appropriately quarantines him or herself, hopes in reward from Allah, and accepts that whatever happens is from Allah’s divine decree. Such a believer may be rewarded with the gift of martyrdom. Thus, the test of this affliction may be a means of forgiveness, elevation of rank, and the reward of martyrdom for the believer.

Figure 1. Pathways to Mercy and Punishment

Muslim beliefs about the coronavirus as punishment

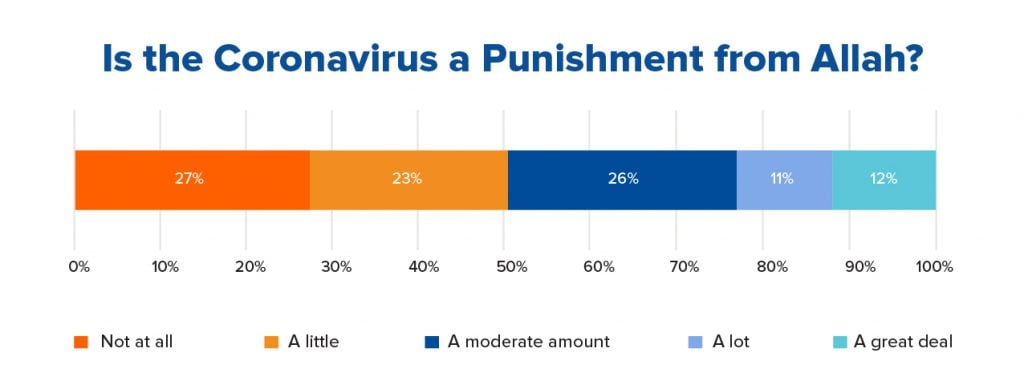

In order to best provide practical solutions around the question of the coronavirus being a punishment and a test, Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research surveyed over 1800 American Muslims who were diverse with respect to age, education, and race. The sample was generally religious in practice.[25]

We asked respondents how much they believed the coronavirus was a punishment. 27% responded that it was not a punishment at all, 26% said a moderate amount, and 12% said a great deal.

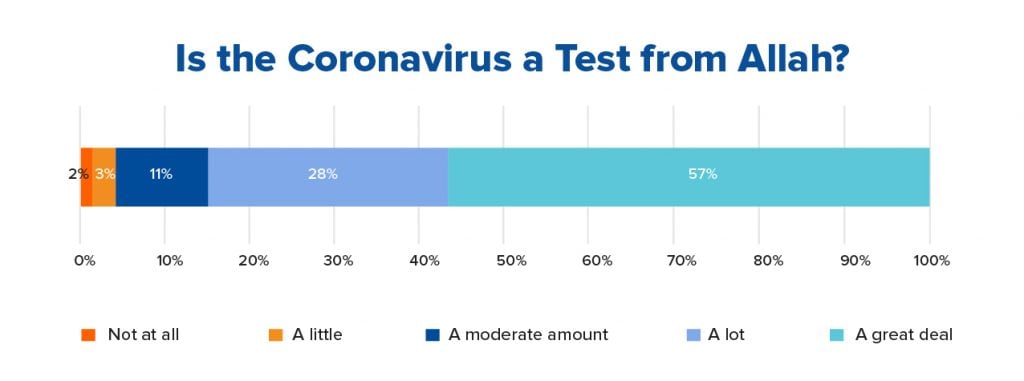

When asked if the coronavirus was a test from Allah, 84% said they believed that it was a major test from Allah.

We also asked how many blessings they had seen as a consequence of the pandemic. 53% said they had witnessed many blessings from Allah since the spread of the coronavirus, whereas 20% reported seeing either few or no blessings at all.

Figure 2. Muslim Beliefs about the Coronavirus as a Punishment and Test

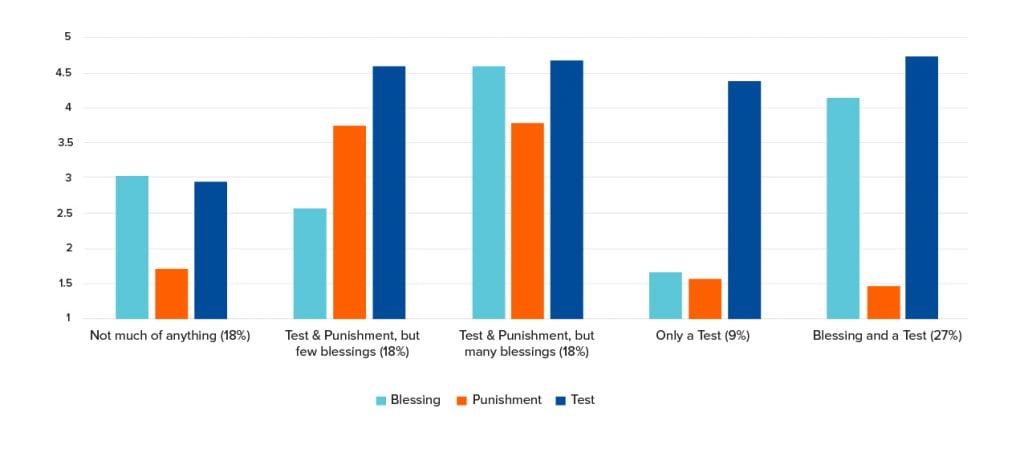

We were most interested in investigating how people’s beliefs about the coronavirus as a punishment, test, or blessings co-occurred. In order to do this, we used cluster analysis to group people into different patterns of beliefs.[26] We found the following five patterns of beliefs, and we summarize the results of each group below.

Figure 3. Patterns of Beliefs about Punishment, Test, and Blessings

American Muslims have different patterns of beliefs regarding the coronavirus as a test, a punishment, and whether they have witnessed any blessings as a result of it. The overwhelming majority believe it is a serious test from Allah and many consider it a punishment. We learn from the results that those who read the Qur’an regularly were more likely to see blessings in this hardship, even if they also see the coronavirus as a nearer punishment. The results also show that it may be unhealthy to see the coronavirus as only a punishment and test, as people who felt this way reported higher anxiety and nervousness.

Responding to the coronavirus: Practical steps

Pinpointing exactly what the coronavirus is (a test, a punishment, or both) may not be possible. However, we can ask ourselves, “How have we responded?” “Are we good with our Creator?” This line of questioning is what the Prophet ﷺ directed us to focus on. When a Bedouin came to him asking when the final hour (i.e., the day of Judgment) would be, the Prophet responded with his own question. He asked the Bedouin, “And what have you prepared for it?”[27] What we learn from the Prophet’s response is that we should not worry about matters of the unseen that are out of our control. Such matters are the domain of Allah’s Lordship and our focus should be on what we will be asked about: our response. This is why when the wind would blow strongly, the Prophet ﷺ would not dwell on whether it was being sent as a “nearer punishment” or as a blessing. He would simply raise his hands in du’a, saying, “O Allah, I ask You for its goodness and I take refuge with You from its evil.”[28] The Prophet took both possibilities into account and focused on turning to Allah for the best outcome regardless of what Allah’s true intent was.

Regardless of whether the coronavirus is a specific punishment, a wake-up call, or a general test, we begin by asking Allah for any good that may result from it and we seek refuge in Him from its evil. If it’s a punishment, we seek Allah’s forgiveness. If it’s a wake-up call, we should wake up from our heedlessness and focus on pleasing Allah. If it’s a test, we remain patient, engage in righteous deeds, hope for Allah’s reward, and are content with whatever He decrees. Because we cannot be sure, we need to engage in all the above actions to the best of our ability. This way, we guarantee ourselves that it turns out to be a blessing and a mercy. Thus, the way we react will determine the answer for each one of us.

Protecting ourselves from punishment

If the coronavirus is indeed a compassionate reprimand to humanity to return to Allah, the believers have a responsibility at both the individual and societal level. At the individual level, each person has to focus on their performance in this test by “being mindful of Allah so that Allah is mindful of them.”[29] At the societal level, a believer is an agent for social welfare, which reduces the likelihood of societal afflictions. Allah specifically mentions in the Qur’an that the presence of reformers is something that prevents the destruction of societies.[30] In addition, the following practices have been mentioned by Allah as specifically related to minimizing harm (e.g., punishment) and maximizing benefits.

Faithful gratitude

What would Allah benefit from punishing you if you are grateful and faithful? And ever is Allah Appreciative and Knowing.[31]

Practicing gratitude regularly is one of the best ways to cope with hardships and please Allah. It also leads to better mental and physical health.[32] Take time out of every day to count your blessings and genuinely thank Allah for them. Writing down five blessings daily and writing gratitude letters to people who have helped you in life are both effective ways to practice gratitude.[33]

Seeking forgiveness

And Allah was not to punish them while you are amongst them, and Allah would not punish them while they continue to ask for forgiveness.[34]

Allah promises to protect His servants who seek His forgiveness. Regardless of what mistakes we have made, big or small, Allah can easily forgive them all. “O My servants who have transgressed against themselves, do not despair of the mercy of Allah. Indeed, Allah forgives all sins. Indeed, it is He who is the Forgiving, the Merciful.”[35] The Prophet further said, “If anyone constantly seeks forgiveness, Allah will create a path out of every distress and relief from every anxiety. He will provide sustenance from where they don’t expect.”[36]

Charitable giving

Charity extinguishes the anger of God.[37]

As the coronavirus has placed many people in financial hardship, giving charity during this time is incredibly helpful. Charity is a proof of faith.[38] There are many non-profits, such as masājid and relief agencies, that really need our support. Our charity will additionally shade us on the Day of Judgment, as the Prophet ﷺ said, Every person will be shaded by their charity [on the Day of Judgment] until judgment between people has been completed.”[39]

Social distancing

Plague is like fire and you are its fuel. Therefore, disperse so the plague finds no fuel and gets extinguished.[40]

This statement by ʿAmr Ibn al-’Āṣ highlights the importance of taking the worldly means to protect ourselves from harm. His advice saved the lives of many during the plague of ʿAmwās that afflicted many companions and the people of Syria.[41] Appropriate social distancing constitutes a part of patience during these times.

Steadfastness

Who rescues you from the darknesses of the land and sea when you call upon Him aloud and in private, “If He should save us from this crisis, we will surely be among the thankful.”[42]

Many people invoke the name of Allah during times of difficulty and promise to change their ways. However, once the relief of Allah comes, they forget about the promises they made to Allah. We know that Allah will lift the hardships caused by the coronavirus in due time. Whatever positive changes we make to our lives during these times, including praying regularly or helping others, let’s do our best to continue them when the situation changes for the better. Similarly, whatever bad habits we have been able to abandon during these times, let’s continue to refrain from them when life returns to normal.

Conclusion

The coronavirus may be a difficult test, a compassionate reprimand from Allah to humanity, or both. Despite the challenges we are all facing, Allah intends good for His servants and wants to bring them near to Him. We should find comfort in knowing that “Allah is more merciful to His servants than a mother is to her child.”[43] Part of His mercy is allowing us the opportunity to grow stronger through trials and hardships.

The believers should be introspective during these times and look deeply into their situation. How we react determines whether it's a punishment or blessing. Are we passing the test and coming closer to Allah? Although we are not in complete control of the consequences of the coronavirus, we are in control of our reactions. Whether our trial relates to physical, mental, or financial health, through patience, hope in Allah’s reward, and contentment with His decree, we should find comfort knowing He may grant us the status of martyrdom. As the Prophet ﷺ said to Allah after his ordeal in Ṭāif, “As long as you are not displeased with me, I do not care [what I face]. I would, however, be much happier with Your mercy.”[44]

Notes

[1] “COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic,” Worldometer, last updated April 9, 2020, https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

[2] Julian P. Alexander, “Philosophy of Punishment,” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law & Criminology 13 (1922): 235.

[3] Mohammad Elshinawy, “The Infinitely Merciful and the Question of Hellfire,” Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research, July 10, 2017, https://yaqeeninstitute.org/mohammad-elshinawy/the-infinitely-merciful-and-the-question-of-hellfire/.

[4] For example, the Prophet ﷺ said, “Verily, the most lightly punished of the people of Hellfire on the Day of Resurrection is a man under whose feet are two hot coals that cause his brain to boil.” Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, the book on heart softeners, the chapter on descriptions of paradise and hellfire.

[5] Ibn al-Qayyim al-Jawzīyah, Hādī al-arwāḥ ilá bilād al-afrāḥ (Amman: Dar al-Fikr, 1987).

[6] Qur’an 21:40.

[7] Qur’an 29:40.

[8] Qur’an 32:21.

[9] This has been attributed to Ibn ʿAbbās, Ubayy ibn Kaʿb, Ḥasan al-Baṣrī, Ibrāhīm al-Nakhaʿī, al-Ḍaḥḥāk, ʿAlqamah, Mujāhid, Qatādah, and many others. The other interpretation is that the nearer punishment refers to punishment in the grave.

[10] Qur’an 30:41.

[11] Helen Y. Weng, Andrew S. Fox, Heather C. Hessenthaler, Diane E. Stodola, and Richard J. Davidson, “The Role of Compassion in Altruistic Helping and Punishment Behavior,” PloS One 10, no. 12 (2015); Ernst Fehr and Simon Gächter, “Altruistic Punishment in Humans,” Nature 415, no. 6868 (2002): 137–40.

[12] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, the book of character, the chapter on mercy and affection to children.

[13] Ibn al-Qayyim, Hādī al-arwāḥ.

[14] Burrhus F. Skinner, “Operant Behavior,” American Psychologist 18, no. 8 (1963): 503.

[15] Negative reinforcement occurs when something present (e.g., bad deeds in our record) is removed as a result of a person's behavior, creating a desirable outcome for that person.

[16] An example of this is the hadith of the Prophet ﷺ, “Whoever purifies himself in his house, then walks to one of the houses of Allah to perform one of the duties enjoined by Allah, for every two steps he takes, one will erase a sin and the other will raise him one degree in status.” Saḥīḥ Muslim, the book on masjids and places of prayer, the chapter on walking to the masjid erasing sins and elevating one’s rank.

[17] Qur’an 7:168.

[18] Qur’an 68:32.

[19] Al-ʿIzz ibn ʿAbd al-Salām, Trials and Tribulations (Birmingham, UK: Dar al-Sunnah, 2004).

[20] Not all afflictions are compassionate reprimands. They may also simply be tests meant to elevate the rank of an already righteous individual and to demonstrate how to deal with difficulties. The afflictions that Prophet Ayūb dealt with are an example of nonreprimanding afflictions.

[21] The Prophet ﷺ said, “No hardship, illness, anxiety, grief, harm, or distress—not even the pricking of a thorn—afflicts a Muslim but that Allah will expiate some of his sins by it.” Saḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, the book of drinks, the chapter on what has come pertaining to expiation of sickness.

[22] Qur’an 2:80.

[23] Saḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, the book of medicine, the chapter on reward for patience during the plague.

[24] Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī, Fatḥ al-Bārī (Riyadh: Maktaba Al-Salafiyah, 2008).

[25] The largest categories of respondents were 25–34 (34%), held bachelor’s degrees (39%), and were South Asian (56%). Females comprised 73% of the sample, and 69% of the sample reported praying five times a day.

[26] We first ran a hierarchical agglomerative clustering algorithm (Ward’s method) to determine the best cluster solution. K-means clustering was subsequently performed to fine-tune cluster homogeneity by reassigning cases to the optimal cluster.

[27] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, the book of virtues of the companions, the chapter on the merits of Omar.

[28] Sunan Abī Dāwūd, no. 5097.

[29] Sunan al-Tirmidhī, the book and chapter on descriptions of the day of judgment, heart softeners, and cautiousness.

[30] Qur’an 11:117.

[31] Qur’an 4:147.

[32] Don E. Davis, Elise Choe, Joel Meyers, Nathaniel G. Wade, Kristen Varjas, Allison Gifford, Amy Quinn, Joshua Hook, Daryl R. Van Tongeren, Brandon J. Griffin, and Everett L. Worthington, “Thankful for the Little Things: A Meta-Analysis of Gratitude Interventions,” Journal of Counseling Psychology 63, no. 1 (2016): 20.

[33] The Prophet ﷺ said, “Whoever does not thank people has not thanked Allah.” Sunan Abī Dāwūd, the book of character, the chapter on being grateful for goodness.

[34] Qur’an 8:33.

[35] Qur’an 39:53.

[36] Sunan Abī Dāwūd, the book of seeking forgiveness.

[37] Sunan al-Tirmidhī, the book of zakāt, hadīth 664.

[38] Saḥīḥ Muslim, the book of purification, the chapter on the virtues of ablution.

[39] Ibn Ḥibbān, no. 653.

[40] Ibn al-Athīr, Usud al-ghābah fī maʿrifat al-ṣaḥābah (Beirut: Dar Ibn Hazm, 2012).

[41] The historian, Ibn ‘Asākir, wrote these lines of poetry about the plague of ʿAmwās. “How many brave horsemen and beautiful, chaste women were killed in the valley of ʿAmwās. They had encountered the Lord, but He was not unjust to them. When they died, they were among the non-aggrieved people in Paradise. We endure the plague as the Lord knows, and we were consoled in the hour of death.” Michael W. Dols, “Plague in Early Islamic History,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1974, 371–83.

[42] Qur’an 6:63.

[43] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 5653.