Zakat is Not Just Charity: Unlocking the Transformative Power of Islam’s Third Pillar

Summary

Introduction

The role of the five pillars in upholding devotion to God

The importance of Salat and Zakat in upholding devotion to God

God has made a promise to those among you who believe and do good deeds: He will make them successors in the land, as He did those who came before them; He will empower the religion He has chosen for them; He will grant them security to replace their fear. ‘They will worship Me and not join anything with Me.’ Those who are defiant after that will be the rebels. Establish Salat, give Zakat and obey the Messenger so that you may receive [this] Mercy! (Qur’an 24:55-56)

Features and benefits of Zakat

Establishing and practising the pillar of Zakat

Conditions for effective Zakat

Pooling funds

Focusing locally

The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ sent Mu`adh (may Allah be pleased with him) to Yemen and said, "Invite the people to testify that none has the right to be worshipped but Allah and I am Allah's Messenger; if they obey you in doing so, then teach them that Allah has enjoined on them five prayers in every day and night (i.e., every twenty-four hours); and if they obey you in doing so, then teach them that Allah has made it obligatory for them to pay the Zakat from their property and it is to be taken from the wealthy among them and given to their poor." (Sahih al-Bukhari)

Abu Juhaifah says, “The Zakat officer of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ came and collected Zakat from the rich amongst us and distributed it to our poor. I was then a minor orphan, so he gave me a she-camel.” (Sunan al-Tirmidhi)

It is reported that a Bedouin Arab asked the Messenger of God ﷺ several questions. Among them was, “By God Who sent you, is it God who commanded you to take the Sadaqah from our rich and distribute it to our poor?” The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ answered, “Yes.” (al-Bayhaqi)

Abu 'Ubaid reports that 'Umar (may Allah be pleased with him) wrote in his will, “I ask my successor . . . to take from their ordinary wealth and distribute it among their poor.” (Kitab al-Amwal)

Sa'id bin al Musayyib says “Umar (may Allah be pleased with him) sent Mu'adh as a Zakat collector to Banu Kilab or Banu Sa'd. Mu'adh (may Allah be pleased with him) went there, collected the Zakat, and distributed all of it, leaving nothing. He came back in the same own clothes that he went in.” (Kitab al-Amwal)

Imran bin Husain (may Allah be pleased with him), a Companion, was appointed as a Zakat collector at the time of the Umayyads. When he returned from his mission, he was asked, “Where is the money?” Imran said, "Did you send me to bring you money? I collected it the same way we used to at the time of the Messenger of God ﷺ and distributed it the same way we used to.” (Sunan Abu Dawud)

Ta’us was appointed as a Zakat collector in one of the regions in Yemen. He was asked for his account by the governor and his answer was, “I took from the rich and gave to their destitute.” (Kitab al-Amwal)

Farqad al Sabkhi says, “I took Zakat due on my wealth to distribute it in Makkah. There I met Said bin Jubair (may Allah be pleased with him), who said, ‘Take it back and distribute it in your hometown.’” (Kitab al-Amwal)

Sufyan narrates, “Zakat was taken from al-Rayy to Kufa, but 'Umar bin 'Abd al Aziz (may Allah have mercy on him) ordered it taken back to al-Rayy.” (Kitab al-Amwal)

Abu 'Ubaid says after the above, “Scholars all agree that these reports mean people of every region have priority on their Zakat, as long as they still have anyone in need, or until all the Zakat is distributed.” He goes on, “If the officer transports collected Zakat while there still is need in the region from which it was collected, the government must return it to its region, as did 'Umar bin 'Abd al 'Aziz, and as stated by Sa'id bin Jubair.” (Kitab al-Amwal)

Balancing distribution

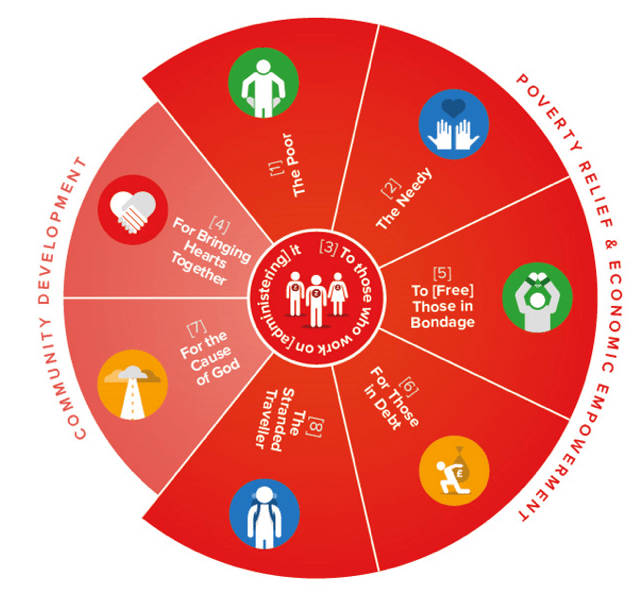

Alms (Zakat expenditures) are only for [1] the poor, [2] the needy, [3] those who administer them, [4] for bringing hearts together, [5] to [free] those in bondage and [6] for those in debt, [7] for God’s cause and [8] for the stranded traveller. This is an obligation from God; God is All-Knowing and Wise. (Qur’an, 9:60)

Case Study: United Kingdom

Conclusions

Notes

[1] Pew Research Center (2017) Report: Europe’s Growing Muslim Population

[2] Related by Abdullah b. Umar; al-Bukhari and Muslim.

[3] Al-Mafatih Fi Sharh al-Masabih

يعني: جعل هذه الأركان الخمسة أصولًا للإسلام، وما عدا هذه الخمسة من أحكام الشريعة فَرْعًا لها، ومثال الإسلام كقصر، وهذه الأركان الخمسة كالأسطوان لذلك القصر، وما بقي من أحكام الشريعة كجدار سطح ذلك القصر، وكالجُدُرِ التي حواليه، وكتزيينه بأنواع النقوش، فمن حفظ هذه الأركانَ الخمسة وسائرَ أحكام الشريعة يكون قصر إسلامه تامًا كاملًا مزينًا، ومن لم يحفظ هذه الأركان الخمسة، ولم يحفظ سائرَ أركان الشريعة يكون قصر إسلامه بغير جدار سطحه، وبغير جدار حواليه، وأما من ترك ركنًا من هذه الأركان فنبيِّنُ بحثه في الحديث الذي يأتي بعد هذا الحديث، إن شاء الله تعالى.( المفاتيح في شرح المصابيح ج 1 ص 56 )

“These five pillars are the foundations of Islam. Besides these five, the rest of the actions branch off from these five. Islam is like a palace and these five are like the pillars for this palace. The remainder of the acts in Islam are like the walls, ceiling, and its decoration. Thus, whoever safeguards these five pillars and the remainder of injunctions in Islam, their palace will be complete and exquisite. Whoever is unmindful in preserving these five foundations and the remainder of injunctions, his palace will be lacking a ceiling and walls.”

[4] Ibn Rajab, Jami’ al-Ulum wal Hikam وَاعْلَمْ أَنَّ هَذِهِ الدَّعَائِمَ الْخَمْسَ بَعْضُهَا مُرْتَبِطٌ بِبَعْضٍ، (جامع العلوم والحكم)

“Know that these five pillars are interconnected.”

[5] Ibn Battal, Sharh Sahih al-Bukhari

قال المهلب: فهذه الخمس هى دعائم الإسلام التى بها ثباته، وعليها اعتماده، وبإدامتها يعصم الدم والمال، (شرح صحيح البخارى لابن بطال)

“These five are the foundations of Islam upon which Islam is kept firm, supported and with which life and wealth are preserved.”

Al-Ithyubi, Dhakirat al-Uqba

وَقَالَ الشيخ عزّ الدين ابن عبد السلام رحمه الله تعالى فِي "أماليه" فِي هَذَا الْحَدِيث إشكالٌ؛ لأن الإسلام إن أريد به الشهادة، فهو مبنيّ عليها؛ لأنها شرط فِي الإيمان، مع الإمكان الذي هو شرط فِي الخمس، وإن أريد به الإيمان، فكذلك؛ لأنه شرط، وإن أريد به الانقياد، والانقياد هو الطاعة، والطاعة فعل المأموربه، والمأمور به هي هذه الخمس، لا عَلَى سبيل الحصر، فيلزم بناء الشيء عَلَى نفسه.

قَالَ: والجواب أنه التذلّل العام الذي هو اللغويّ، لا التذلّل الشرعيّ الذي هو فعل الواجبات، حَتَّى يلزم بناء الشيء عَلَى نفسه. ومعنى الكلام: أن التذلّل اللغويّ يترتّب عَلَى هذه الأفعال، مقبولاً منْ العبد، طاعةً، وقربةً.( ذخيرة العقبى في شرح المجتبى)

Islam in this hadith refers to generic subservience which is the linguistic meaning, Islam (in the hadith) does not refer to the Shar’i meaning which implies the performance of injunctions. This meaning is adopted to prevent the paradox of something being built upon itself. Therefore, the hadith means: Subservience in general is built upon these five actions.

[6] Ibn Hajar, Fatḥ al-Bārī, Beirut: Dār al-Ma’rifah

[7] Imam al-Ayni, Umdat al-Qari

أَن الْإِيمَان أصل للعبادات فَتعين تَقْدِيمه ثمَّ الصَّلَاة لِأَنَّهَا عماد الدّين ثمَّ الزَّكَاة لِأَنَّهَا قرينَة الصَّلَاة (عمدة القاري)

Iman is fundamental to all worship; it must precede everything. Thereafter, Salat is mentioned due to Salat being the support of one’s Deen, thereafter Zakat has mentioned, as it is the companion of Salat.

[8] Mullah Ali al-Qari, Mirqat al-Mafatih

أَرَادَ الْخَمْسَةَ الَّتِي بُنِيَ الْإِسْلَامُ عَلَيْهَا، وَإِنَّمَا خُصَّتَا بِالذِّكْرِ لِأَنَّهُمَا أُمُّ الْعِبَادَاتِ الْبَدَنِيَّةِ وَالْمَالِيَّةِ وَأَسَاسُهُمَا، وَالْعُنْوَانُ عَلَى غَيْرِهِمَا، وَلِذَا كَانَتِ الصَّلَاةُ عِمَادَ الدِّينِ، وَالزَّكَاةُ قَنْطَرَةُ الْإِسْلَامِ، وَقُرِنَ بَيْنَهُمَا فِي الْقُرْآنِ كَثِيرًا، أَوْ لِكِبَرِ شَأْنِهِمَا عَلَى النُّفُوسِ لِتَكَرُّرِهِمَا (مرقاة المفاتيح)

With ‘five’, he was referring to what Islam was founded upon. Salat and Zakat have been specifically mentioned because they are the core and foundation of physical and monetary worship. Hence, Salat is the foundation of Deen whilst Zakat is the bridge to Islam. The two have been interlinked multiple times in the Qur’an. The second possible reason behind Salat and Zakat being mentioned is that they are held in high esteem due to their common occurrence.

[9] Shah Waliullah, Hujjat Allah al-Balighah 2/60

اعْلَم أَن عُمْدَة مَا روعي فِي الزَّكَاة مصلحتان: مصلحَة ترجع إِلَى تَهْذِيب النَّفس، وَهِي أَنَّهَا أحضرت الشُّح، وَالشح أقبح الْأَخْلَاق ضار بهَا فِي الْمعَاد، وَمن كَانَ شحيحا فَإِنَّهُ إِذا مَاتَ بقى قلبه مُتَعَلقا بِالْمَالِ، وعذب بذلك، وَمن تمرن بِالزَّكَاةِ، وأزال الشُّح من نَفسه كَانَ ذَلِك نَافِعًا لَهُ، أَنْفَع الْأَخْلَاق فِي الْمعَاد بعد الإخبات لله تَعَالَى هُوَ سخاوة النَّفس، فَكَمَا أَن الإخبات يعد للنَّفس هَيْئَة التطلع إِلَى الجبروت، فَكَذَلِك السخاوة تعد لَهَا الْبَرَاءَة عَن الهيآت الخسيسة الدُّنْيَوِيَّة، وَذَلِكَ لِأَن أصل السخاوة قهر الملكية البهيمية، وَأَن تكون الملكية هِيَ الْغَالِبَة وَتَكون البهيمية منصبغة بصبغها آخذة حكمهَا، وَمن المنبهات عَلَيْهَا بذل المَال مَعَ الْحَاجة إِلَيْهِ وَالْعَفو عَمَّن ظلم وَالصَّبْر على الشدائد فِي الكريهات بِأَن يهون عَلَيْهِ ألم الدُّنْيَا لَا يقانه بِالآخِرَة، فَأمر النَّبِي صَلَّى اللهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ بِكُل ذَلِك، وَضبط أعظمها وَهُوَ بذل المَال بحدود، وقرنت بِالصَّلَاةِ وَالْإِيمَان فِي مَوَاضِع كَثِيرَة من الْقُرْآن وَقَالَ تَعَالَى عَن أهل النَّار:

{لم نك من الْمُصَلِّين وَلم نك نطعم الْمِسْكِين وَكُنَّا نَخُوض مَعَ الخائضين} .

وَأَيْضًا فَإِنَّهُ إِذا عنت للمسكين حَاجَة شَدِيدَة، وَاقْتضى تَدْبِير الله أَن يسد خلته بِأَن يلهم الْإِنْفَاق عَلَيْهِ فِي قلب رجل، فَكَانَ هُوَ بذلك انبسط قلبه اللألهام، وَتحقّق لَهُ بذلك انْشِرَاح روحاني، وَصَارَ معدا لرحمة الله تَعَالَى

نَافِعًا جدا فِي تَهْذِيب نَفسه، والإلهام الجملى المتوجه إِلَى النَّاس فِي الشَّرَائِع تلو الإلهام التفصيلي فِي فَوَائده، وَأَيْضًا فالمزاج السَّلِيم مجبول على رقة الجنسية، وَهَذِه خصْلَة عَلَيْهَا يتَوَقَّف أَكثر الْأَخْلَاق الراجعة إِلَى حسن الْمُعَامَلَة مَعَ النَّاس، فَمن فقدها فَفِيهِ ثلمة يجب عَلَيْهِ سدها، وَأَيْضًا فَإِن الصَّدقَات تكفر الخطيئات، وتزيد فِي البركات على مَا بَينا فِيمَا سبق. ومصلحة ترجع إِلَى الْمَدِينَة وَهِي أَنَّهَا تجمع لَا محَالة الضُّعَفَاء وَذَوي الْحَاجة وَتلك الْحَوَادِث تَغْدُو على قوم وَتَروح على آخَرين، فَلَو لم تكن السّنة بَينهم مواساة الْفُقَرَاء وَأهل الْحَاجَات لهلكوا، وماتوا جوعا، وَأَيْضًا فنظام الْمَدِينَة يتَوَقَّف على مَال يكون بِهِ قوام معيشة الْحفظَة الذابين عَنْهَا والمدبرين السائسين لَهَا، وَلما كَانُوا عاملين للمدينة عملا نَافِعًا - مشغولين بِهِ عَن اكْتِسَاب كفافهم - وَجب أَن تكون قوام معيشتهم عَلَيْهَا والانفاقات الْمُشْتَركَة لَا تسهل على الْبَعْض أَو لَا يقدر عَلَيْهَا الْبَعْض، فَوَجَبَ أَن تكون جباية الْأَمْوَال من الرّعية سنة.

وَلما لم يكن أسهل وَلَا أوفق بِالْمَصْلَحَةِ من أَن تجْعَل إِحْدَى المصلحتين مَضْمُومَة بِالْأُخْرَى أَدخل الشَّرْع إِحْدَاهمَا فِي الْأُخْرَى. (حجة الله البالغة ج 2 ص 60-61 ط دار الجيل)

“Zakat has captured two types of benefit: a benefit for taming the Nafs (caprice) as it has greed anchored in it which is the most blameworthy of traits. Whoever is greedy, he dies with his heart attached to wealth. He is punished on account of this attachment. Therefore, whoever tames his self with Zakat and eradicates greed from himself, it will be beneficial for him…The second benefit leads back to the city and society as it always incorporates the weak and the needy. These emergencies and incidents afflict different people; thus if there was no method to sympathize with and take care of the needy, they would perish. Not only that, but to implement order in society, wealth is required which supports civil servants, leaders, and officials.”

[10] al-Kasani, Bada'i al-Sana'i 2/3 وَأَمَّا الْمَعْقُولُ فَمِنْ وُجُوهٍ أَحَدُهَا أَنَّ أَدَاءَ الزَّكَاةِ مِنْ بَابِ إعَانَةِ الضَّعِيفِ وَإِغَاثَةِ اللَّهِيفِ وَإِقْدَارِ الْعَاجِزِ وَتَقْوِيَتِهِ عَلَى أَدَاءِ مَا افْتَرَضَ اللَّهُ عَزَّ وَجَلَّعَلَيْهِ مِنْ التَّوْحِيدِ وَالْعِبَادَاتِ وَالْوَسِيلَةُ إلَى أَدَاءِ الْمَفْرُوضِ مَفْرُوضٌ (بدائع الصنائع ج 2 ص 3 ط دار الكتب

“One of the intelligible reasons for Zakat is that it strengthens the weak, empowers the unable, and uplifts them to establish Tawhid (oneness of Allah) and worship ordained by Allah.”

[11] Imam Tabari, Tafsir al-Tabari 14/316 قال أبو جعفر: والصواب من القول في ذلك عندي: أن الله جعل الصدقة في معنيين أحدهما: سدُّ خَلَّة المسلمين، والآخر: معونة الإسلام وتقويته. فما كان في معونة الإسلام وتقوية أسبابه، فإنه يُعطاه الغني والفقير، لأنه لا يعطاه من يعطاه بالحاجة منه إليه، وإنما يعطاه معونةً للدين. وذلك كما يعطى الذي يُعطاه بالجهاد في سبيل الله، فإنه يعطى ذلك غنيًّا كان أو فقيرًا، للغزو، لا لسدّ خلته. وكذلك المؤلفة قلوبهم، يعطون ذلك وإن كانوا أغنياء، استصلاحًا بإعطائهموه أمرَ الإسلام وطلبَ تقويته وتأييده. (جامع البيان في تأويل القرآن ج 14 ص 316 ط مؤسسة الرسالة)

“Abu Ja’far states: The correct opinion according to me is: Allah has given Sadaqah (Zakat) two core functions: Fulfilling the needs of the Muslims and the other is the assistance and strengthening of Islam. Whichever category is to strengthen Islam and its means, then a wealthy or needy person can be given from Zakat. This is because these individuals are not being given Zakat for their needs, rather, it is to assist Islam. It is similar to a person who is given Zakat to strive in the cause of Allah. Such a person can be given regardless of his financial state. Likewise, in the category of winning hearts, people are given Zakat even if they are wealthy. This is a means to improve, strengthen, and assist the state of Islam.”

[12] Stirk C. (2015) An Act of Faith: Humanitarian Financing and Zakat. Global Humanitarian Assistance; IBB/NZF survey; UK National Zakat Foundation data.

[13] Stirk C. (2015) An Act of Faith: Humanitarian Financing and Zakat. Global Humanitarian Assistance.

[14] Al-Qardhawi, Fiqh al-Zakat فقه الزكاة للقرضاوي

[15] Ibn Abidin, Hashiyah ibn Abidin, 5/368

وَأَمَّا بِلَادٌ عَلَيْهَا وُلَاةٌ كُفَّارٌ فَيَجُوزُ لِلْمُسْلِمِينَ إقَامَةُ الْجُمَعِ وَالْأَعْيَادِ وَيَصِيرُ الْقَاضِي قَاضِيًا بِتَرَاضِي الْمُسْلِمِينَ، فَيَجِبُ عَلَيْهِمْ أَنْ يَلْتَمِسُوا وَالِيًا مُسْلِمًا مِنْهُمْ اهـ وَعَزَاهُ مِسْكِينٌ فِي شَرْحِهِ إلَى الْأَصْلِ وَنَحْوُهُ فِي جَامِعِ الْفُصُولَيْنِ. مَطْلَبٌ فِي حُكْمِ تَوْلِيَةِ الْقَضَاءِ فِي بِلَادٍ تَغَلَّبَ عَلَيْهَا الْكُفَّارُ

وَفِي الْفَتْحِ: وَإِذَا لَمْ يَكُنْ سُلْطَانٌ، وَلَا مَنْ يَجُوزُ التَّقَلُّدُ مِنْهُ كَمَا هُوَ فِي بَعْضِ بِلَادِ الْمُسْلِمِينَ غَلَبَ عَلَيْهِمْ الْكُفَّارُ كَقُرْطُبَةَ الْآنَ يَجِبُ عَلَى الْمُسْلِمِينَ أَنْ يَتَّفِقُوا عَلَى وَاحِدٍ مِنْهُمْ، وَيَجْعَلُونَهُ وَالِيًا فَيُوَلَّى قَاضِيًا وَيَكُونُ هُوَ الَّذِي يَقْضِي بَيْنَهُمْ وَكَذَا يُنَصِّبُوا إمَامًا يُصَلِّي بِهِمْ الْجُمُعَةَ اهـ. وَهَذَا هُوَ الَّذِي تَطْمَئِنُّ النَّفْسُ إلَيْهِ فَلْيُعْتَمَدْ نَهْرٌ، وَالْإِشَارَةُ بِقَوْلِهِ: وَهَذَا إلَى مَا أَفَادَهُ كَلَامُ الْفَتْحِ مِنْ عَدَمِ صِحَّةِ تَقَلُّدِ الْقَضَاءِ مِنْ كَافِرٍ عَلَى خِلَافِ مَا مَرَّ عَنْ التَّتَارْخَانِيَّة، وَلَكِنْ إذَا وَلَّى الْكَافِرُ عَلَيْهِمْ قَاضِيًا وَرَضِيَهُ الْمُسْلِمُونَ صَحَّتْ تَوْلِيَتُهُ بِلَا شُبْهَةٍ تَأَمَّلْ، ثُمَّ إنَّ الظَّاهِرَ أَنَّ الْبِلَادَ الَّتِي لَيْسَتْ تَحْتَ حُكْمِ سُلْطَانٍ بَلْ لَهُمْ أَمِيرٌ مِنْهُمْ مُسْتَقِلٌّ بِالْحُكْمِ عَلَيْهِمْ بِالتَّغَلُّبِ أَوْ بِاتِّفَاقِهِمْ عَلَيْهِ يَكُونُ ذَلِكَ الْأَمِيرُ فِي حُكْمِ السُّلْطَانِ فَيَصِحُّ مِنْهُ تَوْلِيَةُ الْقَاضِي عَلَيْهِمْ. (حاشية ابن عابدين ج 5 ص 368 ط السعيد)

“It is stated in Fath al-Qadir: If there is no Sultan, nor any official from whom the duty of Qadha can be accepted as is the state in a few Muslim lands like Cordoba, then it becomes necessary for the Muslims to unite and make one person their Wali (official representative). This Wali should appoint a Qadhi who will judge in their affairs. However, when a non-Muslim appoints a Qadhi for the believers with whom they are happy with, his post will be legally valid.”

[16] Maulana Sajjid Nomani (2017) The Importance of Zakat https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=paRwCtvpQEo

[17] Al-Mawsu’ah al-Kuwaitiyyah al-Fiqhiyya, 23/332

إِذَا فَاضَتِ الزَّكَاةُ فِي بَلَدٍ عَنْ حَاجَةِ أَهْلِهَا جَازَ نَقْلُهَا اتِّفَاقًا، بَل يَجِبُ، وَأَمَّا مَعَ الْحَاجَةِ فَيَرَى الْحَنَفِيَّةُ أَنَّهُ يُكْرَهُ تَنْزِيهًا نَقْل الزَّكَاةِ مِنْ بَلَدٍ إِلَى بَلَدٍ، وَإِنَّمَا تُفَرَّقُ صَدَقَةُ كُل أَهْل بَلَدٍ فِيهِمْ، لِقَوْل النَّبِيِّ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ: تُؤْخَذُ مِنْ أَغْنِيَائِهِمْ فَتُرَدُّ عَلَى فُقَرَائِهِمْ (1) . وَلأَِنَّ فِيهِ رِعَايَةَ حَقِّ الْجِوَارِ، وَالْمُعْتَبَرُ بَلَدُ الْمَال، لاَ بَلَدُ الْمُزَكِّي.

وَاسْتَثْنَى الْحَنَفِيَّةُ أَنْ يَنْقُلَهَا الْمُزَكِّي إِلَى قَرَابَتِهِ، لِمَا فِي إيصَال الزَّكَاةِ إِلَيْهِمْ مِنْ صِلَةِ الرَّحِمِ. قَالُوا: وَيُقَدَّمُ الأَْقْرَبُ فَالأَْقْرَبُ.

وَاسْتَثْنَوْا أَيْضًا أَنْ يَنْقُلَهَا إِلَى قَوْمٍ هُمْ أَحْوَجُ إِلَيْهَا مِنْ أَهْل بَلَدِهِ، وَكَذَا لأَِصْلَحَ، أَوْ أَوْرَعَ، أَوْ أَنْفَعَ لِلْمُسْلِمِينَ، أَوْ مِنْ دَارِ الْحَرْبِ إِلَى دَارِ الإِْسْلاَمِ، أَوْ إِلَى طَالِبِعِلْمٍ (2) .

وَذَهَبَ الْمَالِكِيَّةُ وَالشَّافِعِيَّةُ فِي الأَْظْهَرِ وَالْحَنَابِلَةُ إِلَى أَنَّهُ لاَ يَجُوزُ نَقْل الزَّكَاةِ إِلَى مَا يَزِيدُ عَنْ مَسَافَةِ الْقَصْرِ، لِحَدِيثِ مُعَاذٍ الْمُتَقَدِّمِ، وَلِمَا وَرَدَ أَنَّ عُمَرَ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ بَعَثَ مُعَاذًا إِلَى الْيَمَنِ، فَبَعَثَ إِلَيْهِ مُعَاذٌ مِنَ الصَّدَقَةِ، فَأَنْكَرَ عَلَيْهِ عُمَرُ وَقَال: لَمْ أَبْعَثْكَ جَابِيًا وَلاَ آخِذَ جِزْيَةٍ، وَلَكِنْ بَعَثْتُكَ لِتَأْخُذَ مِنْ أَغْنِيَاءِ النَّاسِ فَتَرُدَّ عَلَى فُقَرَائِهِمْ، فَقَال مُعَاذٌ: مَا بَعَثْتُ إِلَيْكَ بِشَيْءٍ وَأَنَا أَجِدُ مَنْ يَأْخُذُهُ مِنِّي.

وَرُوِيَ أَنَّ عُمَرَ بْنَ عَبْدِ الْعَزِيزِ أُتِيَ بِزَكَاةٍ مِنْ خُرَاسَانَ إِلَى الشَّامِ فَرَدَّهَا إِلَى خُرَاسَانَ. (الموسوعة الفقهية الكويتية ج 23 ص 332 ط دارالسلاسل)

When there is a surplus in Zakat funds in any area, it is permissible to transfer the Zakat funds according to all. However, if there is a need for Zakat locally, it is disliked according to the Hanafi school to transfer Zakat from one area to another. The Hanafis have excluded relatives and needier people from this principle. The Maliki, Shafi’i, and Hanbali schools state that it is necessary to spend Zakat in one’s locality (Shar’i Safr).

[18] Yusuf, H. (2016) Why Zakat begins at home. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ma2mZu9NJ9k

[19] Mattson, I. (2010) Zakat in America: The evolving role of Islamic Charity in Community Cohesion, Lake Institute on Faith and Giving,

[20] Al-Tabari, Tafsir al-Tabari 14/316

قال أبو جعفر: والصواب من القول في ذلك عندي: أن الله جعل الصدقة في معنيين أحدهما: سدُّ خَلَّة المسلمين، والآخر: معونة الإسلام وتقويته. فما كان في معونة الإسلام وتقوية أسبابه، فإنه يُعطاه الغني والفقير، لأنه لا يعطاه من يعطاه بالحاجة منه إليه، وإنما يعطاه معونةً للدين. وذلك كما يعطى الذي يُعطاه بالجهاد في سبيل الله، فإنه يعطى ذلك غنيًّا كان أو فقيرًا، للغزو، لا لسدّ خلته. وكذلك المؤلفة قلوبهم، يعطون ذلك وإن كانوا أغنياء، استصلاحًا بإعطائهموه أمرَ الإسلام وطلبَ تقويته وتأييده. (جامع البيان في تأويل القرآن ج 14 ص 316 ط مؤسسة الرسالة)

“Abu Ja’far states: The correct opinion according to me is: Allah has given Sadaqah (Zakat) two core functions: Fulfilling the needs of the Muslims and the other is the assistance and strengthening of Islam. Whichever category is to strengthen Islam and its means, then a wealthy or needy person can be given from Zakat. This is because these individuals are not being given Zakat for their needs, rather, it is to assist Islam. It is similar to a person who is given Zakat to strive in the cause of Allah. Such a person can be given regardless of his financial state. Likewise, in the category of winning hearts, people are given Zakat even if they are wealthy. This is a means to improve, strengthen, and assist the state of Islam.”

[21] Ibn Taymiyyah, Majmu’ al-Fatawa

الَّذِينَ يَأْخُذُونَ الزَّكَاةَ صِنْفَانِ: صِنْفٌ يَأْخُذُ لِحَاجَتِهِ. كَالْفَقِيرِ وَالْغَارِمِ لِمَصْلَحَةِ نَفْسِهِ. وَصِنْفٌ يَأْخُذُهَا لِحَاجَةِ الْمُسْلِمِينَ: كَالْمُجَاهِدِ وَالْغَارِمِ فِي إصْلَاحِ ذَاتِ الْبَيْنِ (مجموع الفتاوى ج 20 ص 95 ط مجمع الملك فهد)

“Those who accept Zakat are of two types: A group which accepts Zakat for its own benefit such as the needy and the debtor. A group which takes it for the benefit of the Muslims such as one who strives for the benefit of Muslims and the one who takes a financial burden to bring harmony among people at odds.”

[22] Stevenson J, Demack S, Stiell B, Abdi M, Clarkson L, Sheffield Hallam University. (2017) The Social Mobility Challenges Faced by Young Muslims Social Mobility Commission.

[23]Citizens Commission on Islam, Participation and Public Life. (2017) The Missing Muslims report: unlocking British Muslim potential for the Benefit of all (citing 2013 Chatham House study, using YouGov data)