The Character of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ: The Proofs of Prophethood Series

For more on this topic, see Proofs of Prophethood

Introduction

The Character of The Prophet ﷺ

His Honesty

In fact, although the Scottish philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle (d. 1881) certainly had his reservations about Islam, his fascination with the Final Prophet's ﷺ sincerity at times bordered between deep intrigue and apparent conviction. For instance, he explains, “It goes greatly against the impostor theory, the fact that he lived in this entirely unexceptional, entirely quiet and commonplace way, till the heat of his years was done. He was forty before he talked of any mission from Heaven. All his irregularities, real and supposed, date from after his fiftieth year, when the good Kadijah died. All his ‘ambition,’ seemingly, had been, hitherto, to live an honest life; his ‘fame,’ the mere good opinion of neighbors that knew him, had been sufficient hitherto. Not till he was already getting old, the prurient heat of his life all burnt out, and peace growing to be the chief thing this world could give him, did he start on the ‘career of ambition;’ and, belying all his past character and existence, set up [by others] as a wretched empty charlatan to acquire what he could no longer enjoy! For my share, I have no faith whatever in that [imposter theory].”[2] In the same book, Carlyle says, “The lies (Western slander) which well-meaning zeal has heaped round this man (Muhammad) are disgraceful to ourselves only.”

In fact, although the Scottish philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle (d. 1881) certainly had his reservations about Islam, his fascination with the Final Prophet's ﷺ sincerity at times bordered between deep intrigue and apparent conviction. For instance, he explains, “It goes greatly against the impostor theory, the fact that he lived in this entirely unexceptional, entirely quiet and commonplace way, till the heat of his years was done. He was forty before he talked of any mission from Heaven. All his irregularities, real and supposed, date from after his fiftieth year, when the good Kadijah died. All his ‘ambition,’ seemingly, had been, hitherto, to live an honest life; his ‘fame,’ the mere good opinion of neighbors that knew him, had been sufficient hitherto. Not till he was already getting old, the prurient heat of his life all burnt out, and peace growing to be the chief thing this world could give him, did he start on the ‘career of ambition;’ and, belying all his past character and existence, set up [by others] as a wretched empty charlatan to acquire what he could no longer enjoy! For my share, I have no faith whatever in that [imposter theory].”[2] In the same book, Carlyle says, “The lies (Western slander) which well-meaning zeal has heaped round this man (Muhammad) are disgraceful to ourselves only.”His Austerity and Asceticism

Edward Gibbon (d. 1794), a historian and member of England’s Parliament, wrote, “The good sense of Muhammad despised the pomp of royalty. The Apostle of God submitted to the menial offices of the family; he kindled the fire; swept the floor; milked the ewes; and mended with his own hands his shoes and garments. Disdaining the penance and merit of a hermit, he observed without effort or vanity the abstemious diet of an Arab.”[4] In other words, he ﷺ not just endured the coarseness of an austere life, but it flowed naturally from him. He was not trying to encourage monkhood or self-deprivation, nor was he faking this minimalism to earn praise from the people. Gibbons continues, “On solemn occasions, he feasted his companions with rustic and hospitable plenty. But, in his domestic life, many weeks would pass without a fire being kindled on the hearth of the Prophet.”

Edward Gibbon (d. 1794), a historian and member of England’s Parliament, wrote, “The good sense of Muhammad despised the pomp of royalty. The Apostle of God submitted to the menial offices of the family; he kindled the fire; swept the floor; milked the ewes; and mended with his own hands his shoes and garments. Disdaining the penance and merit of a hermit, he observed without effort or vanity the abstemious diet of an Arab.”[4] In other words, he ﷺ not just endured the coarseness of an austere life, but it flowed naturally from him. He was not trying to encourage monkhood or self-deprivation, nor was he faking this minimalism to earn praise from the people. Gibbons continues, “On solemn occasions, he feasted his companions with rustic and hospitable plenty. But, in his domestic life, many weeks would pass without a fire being kindled on the hearth of the Prophet.” According to Washington Irving (d. 1859), an American biographer and diplomat, “He was sober and abstemious in his diet and a rigorous observer of fasts. He indulged in no magnificence of apparel, the ostentation of a petty mind; neither was his simplicity in dress affected but a result of real disregard for distinction from so trivial a source … His military triumphs awakened no pride nor vainglory, as they would have done had they been effected for selfish purposes. In the time of his greatest power, he maintained the same simplicity of manners and appearance as in the days of his adversity. So far from affecting a regal state, he was displeased if, on entering a room, any unusual testimonials of respect were shown to him.”[5]

According to Washington Irving (d. 1859), an American biographer and diplomat, “He was sober and abstemious in his diet and a rigorous observer of fasts. He indulged in no magnificence of apparel, the ostentation of a petty mind; neither was his simplicity in dress affected but a result of real disregard for distinction from so trivial a source … His military triumphs awakened no pride nor vainglory, as they would have done had they been effected for selfish purposes. In the time of his greatest power, he maintained the same simplicity of manners and appearance as in the days of his adversity. So far from affecting a regal state, he was displeased if, on entering a room, any unusual testimonials of respect were shown to him.”[5] Bosword Smith (d. 1908), a reverend, schoolmaster, and author writes, “Head of the State as well as the Church; he was Caesar and Pope in one; but he was Pope without the Pope’s pretensions, and Caesar without the legions of Caesar, without a standing army, without a bodyguard, without a police force, without a fixed revenue. If ever a man ruled by a right divine, it was Muhammad, for he had all the powers without their supports. He cared not for the dressings of power. The simplicity of his private life was in keeping with his public life.”[6]

Bosword Smith (d. 1908), a reverend, schoolmaster, and author writes, “Head of the State as well as the Church; he was Caesar and Pope in one; but he was Pope without the Pope’s pretensions, and Caesar without the legions of Caesar, without a standing army, without a bodyguard, without a police force, without a fixed revenue. If ever a man ruled by a right divine, it was Muhammad, for he had all the powers without their supports. He cared not for the dressings of power. The simplicity of his private life was in keeping with his public life.”[6]His Bravery

His Perseverance

His Optimism

His Followers

David George Hogarth (d. 1927), a British scholar and archeologist, said, “Serious or trivial, his daily behavior has instituted a canon which millions observe this day with conscious memory. No one regarded by any section of the human race as Perfect Man has ever been imitated so minutely. The conduct of the founder of Christianity has not governed the ordinary life of his followers. Moreover, no founder of a religion has left on so solitary an eminence as the Muslim apostle.”[15]

David George Hogarth (d. 1927), a British scholar and archeologist, said, “Serious or trivial, his daily behavior has instituted a canon which millions observe this day with conscious memory. No one regarded by any section of the human race as Perfect Man has ever been imitated so minutely. The conduct of the founder of Christianity has not governed the ordinary life of his followers. Moreover, no founder of a religion has left on so solitary an eminence as the Muslim apostle.”[15]

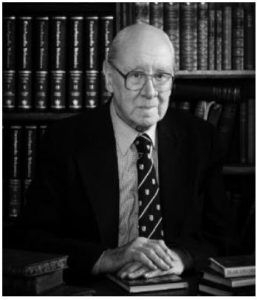

William Montgomery Watt (d. 2006), a Scottish historian and Emeritus Professor in Arabic and Islamic Studies, wrote, “His readiness to undergo persecution for his beliefs, the high moral character of the men who believed in him and looked up to him as a leader, and the greatness of his ultimate achievement – all argue his fundamental integrity. To suppose Muhammad an imposter raises more problems than it solves. Moreover, none of the great figures of history is so poorly appreciated in the West as Muhammad… Thus, not merely must we credit Muhammad with essential honesty and integrity of purpose, if we are to understand him at all; if we are to correct the errors we have inherited from the past, we must not forget that conclusive proof is a much stricter requirement than a show of plausibility, and in a matter such as this only to be attained with difficulty.”[17]

In the next essay, we will examine how the Prophet’s message from the Divine was even more outstanding than the unparalleled excellence of his character.

Notes

[1] Collected by al-Bayhaqi in as-Sunan al-Kubrā (12477), Ibn Kathīr in al-Bidāya wan-Nihāya (3/218-219), and aṭ-Ṭabari in Tārīkh al-Umam wal-Mulook (2/372)

[2] See: On Heroes, Hero Worship, and the Heroic in History, by Thomas Carlyle

[3] Collected by al-Bukhāri (1043)

[4] The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, by Edward Gibbon, Chapter 50

[5] Mohamet and His Successors, by Washington Irving

[6] Muhammad and Muhammadanism, by Bosword Smith

[7] Collected by Aḥmad (619)

[8] Collected by Muslim (4388)

[9] Collected by at-Tirmidhi (5/351) and al-Ḥākim (2/313)

[10] Collected by al-Bukhāri in al-Adab al-Mufrad, Book 14, Hadith 303

[11] Collected by al-Bukhāri (3059) and Muslim (1795)

[12] Collected by Ibn Hishām in as-Sīra (2/70-72) and Ibn Sa‘d in aṭ-Ṭabaqât al-Kubrā (1/211-221)

[13] Some people cite a narration from az-Zuhri about the Prophet ﷺ having suicidal ideations when the revelation paused for a short period (to increase his longing for the angelic visits, and to ensure he would never take this revelation for granted). Even if one overlooks the fact that this narration has a mu‘allaq (incomplete) chain, it simply portrays the suffering, turmoil, and sadness that he endured and was not deterred by. After all, he ﷺ never surrendered to these passing thoughts or impulses and threw himself off the mountain, but rather wrestled with them successfully. Therefore, this only proves – if anything – that his optimism overrode his pains, and that nothing about his life and human nature was ever hidden.

[14] Collected by al-Bukhāri (3866, 4663, 4692) and Muslim (2381)

[15] Arabia, by D.G. Hogarth, first published in 1923

[16] The Columbia History of the World, 1st Edition, p. 264

[17] Muhammad at Mecca, by William Montgomery Watt, Oxford University Press (1953), p. 52