Du’as of the Enslaved: A Journey Through Images

May 21, 2018

Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research.

For more on this topic, see Black Heritage

The images found herein were made available through the generosity of the Arquivo Público do Estado da Bahia in 2018 and were photographed by the microfilm department’s staff member and resident photographer, Tom Lança.

*(Image not identifiable within my own records)*

On the 27th night of Ramadan in January of 1835, hundreds of enslaved and free West African Muslims in Brazil set into motion one of the most meticulously-planned rebellions found within the archives of the Americas. These Muslims adorned their necks with strings tied to verses of the Qur’an, placed du’as within their pockets, and adorned their bodies with long, white garments. Dozens of the rebels gathered in a rented home to have suhur right before they were set to strike at fajr. Unfortunately, this home was discovered by state authorities, setting the rebellion into motion hours before the rebels had planned. This in turn destabilized the plans for the rebellion, and the revolt was put down within just a few hours.

What was special about this rebellion was not the mere act of resistance nor the participation of Muslims. Rather, it was the fact that the idea for this rebellion was born out of secret madrassas and musallas placed all around the Brazilian state of Bahía in an effort to educate enslaved and free black Muslims about the Qur’an. The documents made within these madrassas, found both on the bodies of the fallen rebels and within their homes, were kept as police records and today serve as testimonies to the faith of the black and enslaved martyrs of Islam.

We are about to set on a journey made possible through the inscriptions of these venerable Muslims. May Allah make us worthy of their prayers.

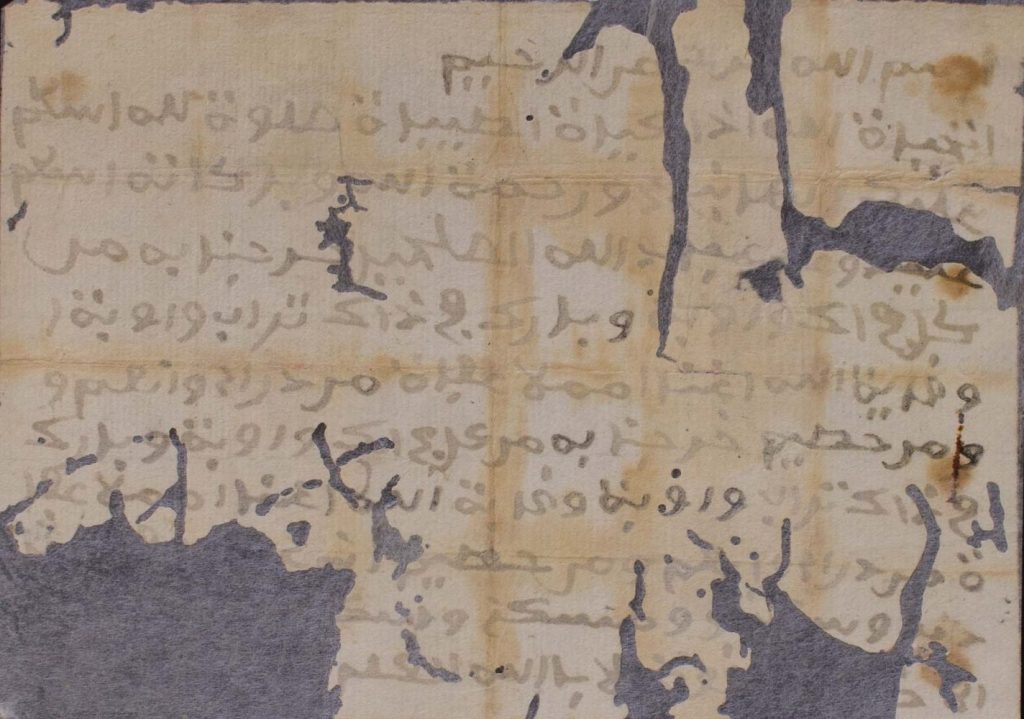

This dilapidated image shows the first chapter of the Qur’an, the Fatiha, found in the home of a Muslim by the name of Torquato. “In the name of God, The Merciful, The Compassionate. Praise the Lord of all the worlds, The Merciful, the Compassionate. Gift us the straight path, the path of those on whom You have bestowed blessings, and not the path of those on whom you have bestowed wrath, nor the path of those who are astray.”

The remaining traces of this letter indicate that it was written by a Muslim named Abu Malak to Abu Habsabi. The first line shows the basmala in a clearly recognizable format. The second line says, “O, Allah, You are my Lord, there is not deity except for God.” The rest of the second line probably included the name Muhammad, peace be upon him, since the third line says, “you are my messenger,” followed by another line referencing Allah, saying, “And there is no power except in you.” The rest of the third line says, “and indeed there is no…,” but the noun here is cut off. The fourth line says, “To Abu Habsabi, forgive…,” perhaps a plea to Allah to either forgive Abu Habsabi’s sins or those of the sender. The final line then might indicate “our sins,” or “his sins.” The blurry Portuguese inscription at the bottom, written by Brazilian authorities after the rebellion, says something along the lines of, “To the negro Antonio, belonging to the state’s authority,” indicating that the recipient of this mail was called by the Portuguese name Antonio.

This du’a was written by an enslaved man by the name of Domingos from the Hausa people. The long du’a includes various indiscernible lines due to the dilapidation of the paper, the blurring of the ink, and Domingo’s wording. The first few lines are venerations of Allah through calling upon Allah’s attributes such as magnanimity and compassion. The fourth line says, “Oh Generous God, grant me sustenance wherever I may be and grant me contentment.” Line six says, “Praise be to God who has removed all sadness.” Throughout lines ten to eleven, and then again throughout lines fifteen through seventeen, Domingos asks Allah to grant him “peace and a peaceful abode.” Lines twenty through twenty-two say, “Bless this earth and bless our return, indeed God is capable of granting us that return, as He is Omnipotent, and there is no power and no strength except in God.”

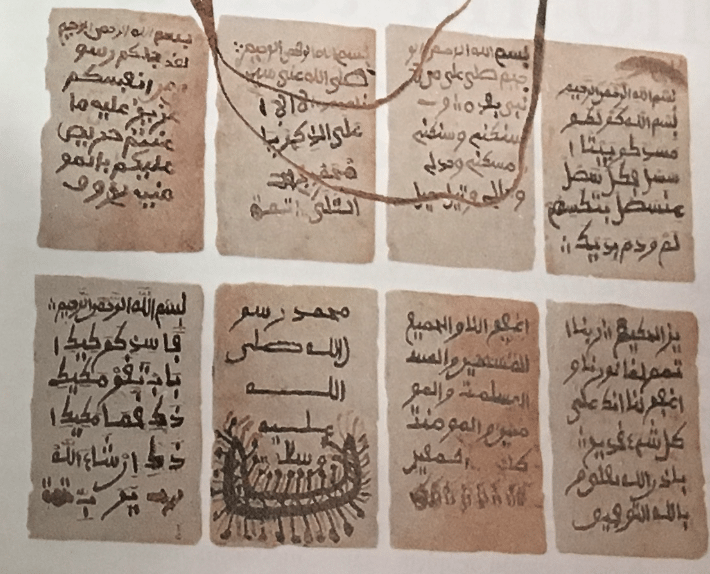

This paper was also found in home of the enslaved Hausa, Domingos. Rather than acting as a written du’a, the formulaic expressions within each box are meant to identify various parts of a prayer. Overall, the prayer begs Allah to bless the city of God and to grant them refuge from every place. The third box to the left may indicate a prayer regarding the rebellion, but this is unclear. The lines at the bottom say, “There is no power or strength except in God, the elevated and majestic.”

The following dua was also found within the files of the enslaved Hausa, Domingos. The opening lines are quite powerful and read, “In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful. Bless us from the terrors and evils and fortify us against all of the defamations against us, and purify us through all of the shame imposed upon us.” Lines seventeen through nineteen read, “I ask you to grant me the love that you have for the poor and I trust that you will forgive me and have compassion towards me. I ask you, our Lord...”

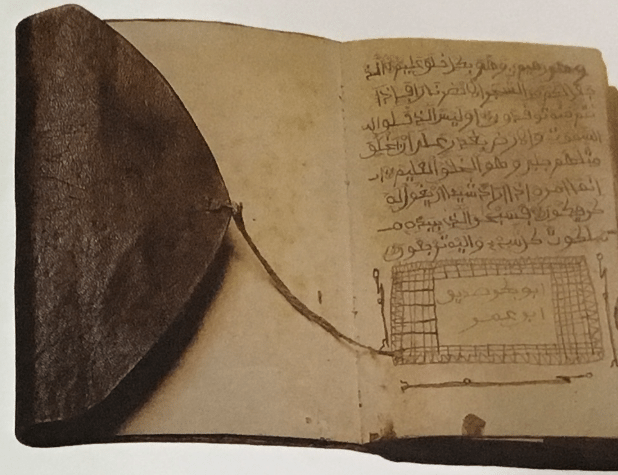

The following images are from the magazine Memórias da Bahia, Volume 10, Universidade Católica da Bahia.

Loose pages from the archives.

Book of prayers from the archives

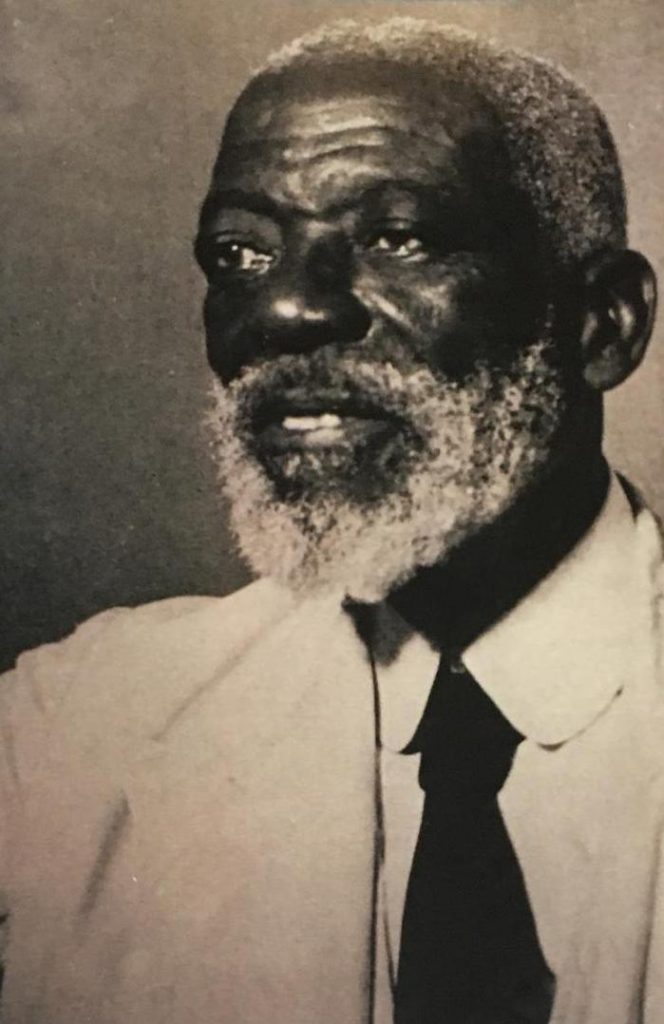

Manoel do Nascimento Santos Silva, also known as Gibirilu, the last known survivor of the revolt in Bahia.

This unnamed Brazilian Muslim woman seems to be wearing prayer beads around her neck and wrists.