In 1915, the modern Ku Klux Klan, a notorious white supremacist group was born in Stone Mountain, Georgia. The Klan was first formed during the Reconstruction years after the Civil War. This early group died out around 1871 only to reemerge in the midst of World War I. It was this modern Klan that would become infamous and flourish across the nation. The Klan’s platform affirmed white supremacy, hatred towards Catholics and Jews, and a vitriolic opposition to the Civil Rights Movement. It was during this era that James Venable, a white supremacist Georgia lawyer, emerged and revived the Ku Klux Klan, establishing it in Stone Mountain, Georgia. He served as mayor of the city from 1946-1949 and led the Klan for 25 years! With incredible irony, it was this same man who later supported my father in his bid to serve on the Stone Mountain City Council and later, as the first African American mayor of the city of Stone Mountain. I share my father’s story for the first time in order to both honor his life and legacy as well as to remind us of the continued work that needs to be done by American Muslims.

My father was born Charles Burris on March 5, 1951, in Alexandria, Louisiana. He was an orphan, quite literally left as an infant on the doorstep of the woman I would come to know as “Mama,” his adoptive mother. Although his biological parents were unknown to him until the day he passed, and to me and my sisters as well, his adoptive parents were church-going, Southern Baptist educators. Mama, my grandmother, was Vermont Burris, a high school English teacher. Her husband Seymour Burris, was an elementary school teacher who would later become blind. My father used to help care for him as a young child and therefore grew up valuing education and helping others in need at an early age. Mama taught him mathematics and the works of Shakespeare before he reached the first grade and would make him memorize several parts. My grandparents were also very active volunteers in the community and for the NAACP. They used to take my father with them to help register other blacks in their community to vote. At the age of 16, my father graduated from Peabody High School in Louisiana and was accepted into Morehouse College in 1967 as a Merrill Scholar. He used to hold various positions in student government as an undergraduate, competed on the swim and diving teams, reported for the campus newspaper, and attended Morehouse’s Saturday seminars, which were taught by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

One day my father was late to class and entered the room after having gotten into an altercation with another person. Dr. King noticed my father’s appearance and demeanor and asked him what had happened. My father informed Dr. King that another person had provoked him into an altercation. Dr. King then replied, “My son, so long as you allow another person to move you towards aggression, you will always be a slave!” Those words stuck with my father and he devoted himself towards fighting against injustice through intellectual and not physical means, a lesson he imparted to me on numerous occasions later in life.

My father remained very active in local politics because he truly believed that his mission was to make people’s lives better by making government work better for them. He called this his social mission in life. In 1968 he worked on the vice mayoral campaign of Maynard Jackson, who would become the first African American mayor of the city of Atlanta. In 1970 he worked on Ambassador Andrew Young’s congressional campaign. During this time, he met my mother, Jeannie Dowell, fell in love, and married.

He was a member of the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity at Morehouse College and he and my mother used to frequent the Canterbury House interfaith center, known as the Absalom Jones Episcopal Center on the Atlanta University Campus (AUC). That was also the place frequented by many Sunni Muslims who used to establish the Friday Prayer service there. Both my parents used to watch the Muslim students pray. My father was always religiously inclined, constantly in search for the true religion. The campus chaplain allowed interfaith talks quite often and it was in that environment that my father first encountered Islam. He later got a copy of the Qur’an and began to read it, noticing what he used to describe as, “the same God as in the Bible.” The thought of being abandoned by his original parents always haunted my father and he never moved past it. But when he opened the Qur’an and came across chapter 93, the message spoke deeply and profoundly to him:

In the name of God, the Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy. By the morning brightness and by the night when it grows still; your Lord has not forsaken you, nor does He hate you, and the future will be better for you than the past; Your Lord is sure to give you so much that you will be pleased. Did He not find you an orphan and shelter you; find you lost and guide you; find you in need and satisfy your need? So do not be harsh with the orphan and do not chide the one who asks for help; Speak about the blessings of your Lord! (Qur’an 93: 1-11)

My father converted to Islam in October of 1975 after reading this chapter and later, as an American Muslim convert, he always wept whenever he read or heard this chapter of the Qur’an recited. He also was particularly fond of poetry and one of his favorite poets was a famous Lebanese American poet named Gibran Khalil Gibran. My father also learned in Islam that the name “Khalil” was an epithet of Prophet Abraham and changed his name to “Charles Khalil Burris.” Two years later, he would change my name legally to Khalil.

My father encountered various early American Muslim communities in Atlanta. First was the Twelver-Shia community. He admired their love of books and used to read on Shiism although he would later express doubts about the doctrine of the occultation of the twelfth Imam. He enrolled in law school at John Marshall Law School in Atlanta and received his law degree. In 1979, the year my father finished law school and passed the Georgia State Bar exam, the Shia community he was affiliated with left for Iran after the Iranian Revolution. Next, my father and mother moved to the community led by one of the most famous Imams in the United States, Imam Jamil al-Amin. Formerly H. Rap Brown, Imam Jamil had converted to Islam in 1971 in Rikers Island Prison and became one of the most famous and influential American Muslim leaders of the late 20th century. Imam Jamil was the leader of a rapidly expanding network of over 25 Muslim communities across the Caribbean and North America. The Atlanta West End was the headquarters of the network and a large segment of the community were ex-convicts who had converted to Islam in prison and vowed to reform their lives—just like brother Malcolm X!

My parents’ home (646 Atwood Street at the time) served as a makeshift proto-library for the community. I remember as a child a constant barrage of strangers coming into our home, sitting down and reading new books about Islam that they had never heard of before, such as Bukhari and Muslim, two household names of Islam’s most notable canonical texts. As a child, I grew up in Imam Jamil’s mosque and spent much of my childhood in his corner shop speaking and engaging with him about a variety of topics. My father had several disagreements with Imam Jamil regarding some issues at the time and, notwithstanding my father’s great respect for him as a proven leader, those disagreements led my father to maintain what he called a “close but healthy distance.” During this time, my father worked as a researcher and crime analyst for the city of Atlanta, a position he held for two years. It was then that he would cultivate a stronger relationship with a different Imam, Imam Plemon al-Amin of the World Community of Imam W. D. Muhammad. Imam Plemon, a recent graduate of Harvard University, had converted to Islam after Harvard and wanted to help elevate and transform his community from the harms of drugs and the Vietnam War, both of which had had devastating impacts. My father and Imam Plemon became friends and it was at Imam Plemon’s mosque that my father met his spiritual mentor, Shaykh Abdur-Rashid from Nigeria. My father used to study Arabic and Islamic studies with Shaykh Abdur-Rashid, a graduate of the Islamic University of Medina, Saudi Arabia, who would have a profound impact on my father—so much so that my father changed our last name legally from his (Burris) to “Abdur-Rashid.” From 1980 onward, both me and my father legally became Khalil Abdur-Rashid, he the senior and I the junior. As a family of African American converts, we were the ‘Abdur-Rashid’ family. My mother changed her name also from Jeannie Dowell to Jihan Abdur-Rashid.

On the advice of the Shaykh, my father decided to move to Saudi Arabia to find a community there and learn more about Islam. This was in 1980 and there was a frustrating climate of the newly emerging Islam in America. At the center of many convert Muslim’s frustrations was the blurred line that rendered the boundary between cultural and religious Islam indistinguishable. My father, along with two other friends of his, were accepted to the University of Medina and traveled to study there.

My father stayed for one year and returned in 1981. He possessed a utopic and nostalgic vision of what life in Medina, the birthplace of Islam, was like. As a child of the South, and being especially dark-complexioned, his experience with racism in America was like that of many other Blacks in the South. My father witnessed a cross burning on his front lawn as a child; in college, he was taught by and influenced by Dr. King; my father’s classmates at Morehouse were Samuel L. Jackson and Spike Lee. And as an Alpha man, he knew well the struggles of being Black in America. Thinking he would find what Malcolm found in his travel to Arabia, he left with hope and optimism but was smart enough to go alone first to survey the landscape. Leaving behind my mother, myself and my three sisters at the time, my father journeyed to Arabia only to return with negative experiences that would forever imprint themselves deep within his consciousness.

I don’t know much about what happened to my father during that year in Arabia except for two things: 1) he studied Arabic and Islamic studies, and 2) some people there used to address him as “boy” which both enraged and hurt him. Some tried to explain the reasoning behind calling him ‘boy,’ saying they thought he was African at first glance and not American—as if that were an actual justification. My father returned after one year scarred by his experience of what he called the ‘sickness of racism by Muslims who should know better.’ My father told my mother that Arabia was not a place where African Americans should raise their children and that our job was to make life here in America meaningful for Muslims.

After returning, my father worked as an urban planner for the city of Atlanta during the time when Maynard Jackson was Mayor (1974–1982) of Atlanta. During that time, a group of Muslims who were students from abroad at Georgia Tech got together to establish a mosque in central downtown Atlanta, called the Al-Farooq Mosque, now the largest mosque in Atlanta. They recruited my father to help work on the project. My father, who was the only Muslim who worked in Atlanta City Hall at the time, was able to get the land chartered and enabled the establishment of the mosque. After the mosque was established and construction began, the original founders, who included my father and the other students, who were now working professionals, refused to offer my father a place on the board of the mosque. Although I was not yet 10 years old, I remember the argument in the mosque between my father and the others and how he felt that he had a right to serve as a board member in the community and how he was denied this in favor of others. My father took this incident to his grave with him and considered it an act of betrayal by people who acted in hypocrisy. While not knowing all of the details, I am able to say that my father attributed the cause of the incident to racism towards African Americans on the part of immigrant Americans from Arab and South Asian backgrounds. He used to tell me, “Khalil, I can take an enemy in white sheets, but I can’t take the snake in the grass that bites you from behind when you don’t see it coming.” My father predicted that as long as intra-communal Muslim racism persists, the American Muslim community will never realize its full potential. He used to tell me, “Khalil, because of racism, the Muslims aren’t ready for prime time!” He never got over being damaged by the community overseas and in the local mosque, a problem that later contributed to the separation and later divorce between him and my own mother. They would always love each other I would later learn, but the divisions in the community bitterly divided them, for while he felt too damaged to work within the Muslim community, my mother, caring for me and my three younger sisters at the time, felt she had a need and responsibility for her children to remain rooted within the community. My father needed to find and nurture himself after the damage and he decided to work on a different front in order to both heal himself and work on healing others. He decided to remain a Muslim but a closet-Muslim, never going to the mosque or any events, even during Ramadan, but maintaining the prayer and doctrinal tenets of Islam. He relied on what he learned in the classroom of the University of Medina and the spiritual and doctrinal practices he learned from the Shaykh, allowing himself to be self-guided in the domain of being a believer without a community.

My father retreated from the American Muslim community and instead went back into local American politics, changing his name legally from “Khalil Abdur-Rashid” back to Charles Burris, as it was before. Some called him an apostate, but others denied this, knowing his positions and just decided to leave him alone and root for him from afar.

He moved to Stone Mountain, Georgia, land of the Klan then and used to witness Klan marches and celebrations downtown on Main Street every year. This was in the late 1980s to early 1990s. He served on the Dekalb County School board, then on the Stone Mountain City Council from 1991 to 1996. He maintained several high-ranking government positions, including having worked for the late Senator and Secretary of the State of Georgia, Max Cleland. In 1994, my father developed his own computer software company as a side business called MountainWare Ltd.

During his time in public service, my father was deeply troubled by the racism he encountered in his old religious community as well as the persistent Klan marches in his local community. He also wanted Stone Mountain to be a more family-oriented and diverse place. He once complained about there not being enough sidewalks in Stone Mountain and someone said to him, “instead of complaining why don’t you do something about it.” He later told me that this was his motivation to run for city council and eventually mayor!

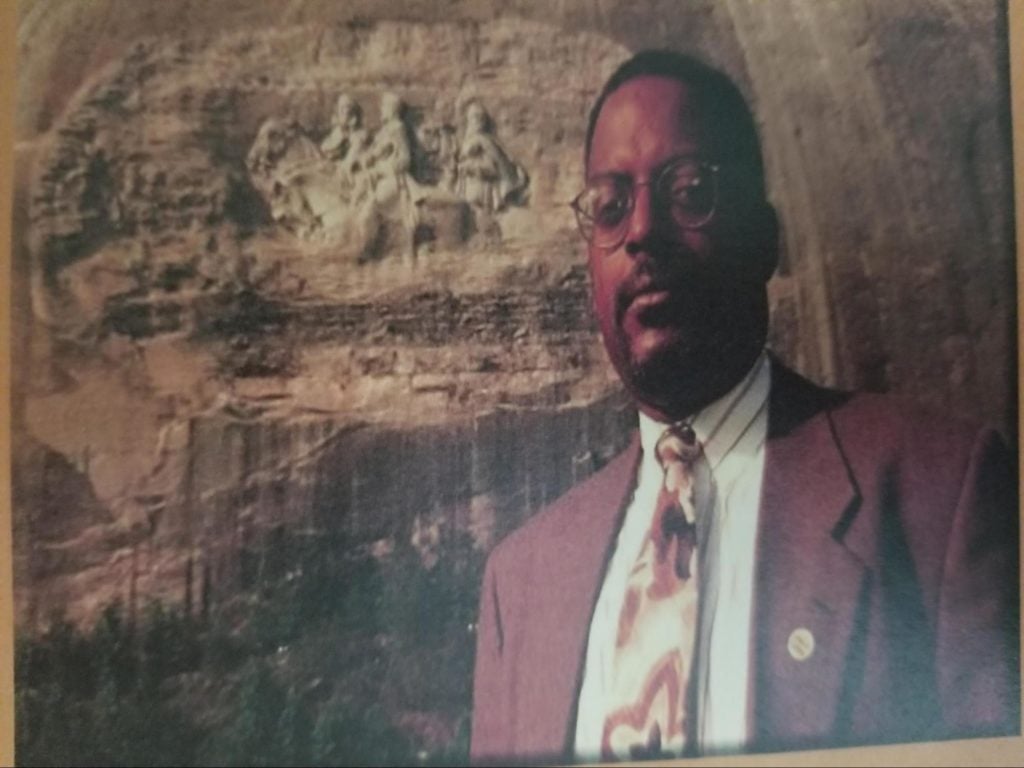

My father began his campaign for mayor of Stone Mountain, a town with 6,700 residents at the time; the site of the world’s largest Confederate Memorial invoked by Dr. King in his “I Have a Dream” speech and at a time when the KKK was actively marching down Main Street and burning a cross adjacent to Stone Mountain property. My father used to publish and distribute a newsletter called “The Burris Report” that detailed his goals and vision. It was this publication that caught the attention of many people, including James Venable.

Mr. James Venable, the grand wizard of the Klan, was the leader of the KKK for 25 years and his father and uncle co-owned the mountain until the State of Georgia purchased it from them in 1958. The KKK used to burn a cross atop the mountain until the late ’60s after which they later burned it on the property owned by Mr. Venable on the base of the mountain. Mr. Venable’s ancestors turned Stone Mountain, the largest exposed piece of granite in the world, into a rock quarry and became wealthy from selling its stone for major construction projects. It is known that the then Klan-owned Stone Mountain provided the raw building materials for the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, The Panama Canal, Fort Knox, the steps of the U.S. Capitol building, the U.S. Treasury, and the Suez Canal. Mr. Venable himself was a very successful attorney whose record included defending the bombers of the Hebrew Benevolent Temple Bombing in Atlanta of a Reform Jewish congregation as well as representing some blacks accused of crimes. He allegedly won an acquittal for a black man accused of murder and later won an appeal for two Black Muslims in Louisiana convicted on charges stemming from a police raid on their mosque. The $25,000 he won from that suit was supposedly funneled into his Klan.

Mr. Venable’s support for my father was surprising to some but not to others who knew my father. My dad convinced him to vote for him and my father always believed he could work to transform hate into hope, as he put it—so long as he knew what he was dealing with. He preferred dealing with people who were direct and upfront and could not work at all with hypocrisy. Former Georgia State Representative, Billy Mitchell, a close friend of my father’s once said that my father was, “very personable, very diligent, and I think that even Mr. Venable came to realize that.” Mr. Venable even posted a campaign sign when my father was running for city council on his own front lawn in support of my father. Six years later, a few years after the death of Mr. Venable, my father ran for mayor and was victorious.

Furthermore, he purchased the home that belonged to Mr. Venable and moved into it, living there for the duration of his tenure as mayor. Initially, my father rebuffed the offer to buy the house but later, he realized that his aversion to the house was also based on prejudice towards a place that he needed to overcome in order to lead effectively. He said that “It wasn’t until we got to know the place and gave it a chance; until we opened the door and looked in, that we realized we liked the house and didn’t care who had owned it.” My father by then had also remarried and both he and my stepmother purchased the house and resided there. The first night after moving in, my father took a framed photo of Dr. King and hung it on the bedroom wall. I spent many nights there with my father and vividly remember my experiences with him. We used to walk the grounds together and talk about leadership, service, life, and lessons. “The house,” as I called it, left an indelible imprint on me. It was my own first personal encounter with the legacy of hate and racism in an intimate space. The first night I slept there was the hardest, for I was obsessed with imagining the kinds of people who had been there before me; how many lives had they terrorized and ruined and how I could live in such a place marked by hate? My father helped me come to terms with my encounter with what would function as a second home (at the time an anti-home) and he taught me that nothing and no one is immune from the possibility of change but that such a change could go both ways, either towards improvement or towards reversal and decay; that we sometimes imprison ourselves in the confines of our own prejudices which contribute to our moral and social decay and that the only question is whether we want to be the change we inspire others towards or not. I learned from “the house” and from my father in it that the shameful past is critical to shaping us today and keeping the past before us helps us fuse the horizons of yesterday with the light of today, a critical compound for the shaping of a hopeful tomorrow. “The house” served as a site of deep thought and reflection of these things for me during my early college years. Whenever I wanted to think about my own purpose in life, I would go to “the house,” a space different from my home but no less significant.

“The house” used to be owned by Mr. Venable’s daughter, Ginger Birts and she maintained a friendship with my father and his wife for many years. She would say, “They’re just great people!” After her father died, she was concerned that the city would not designate a street that carried the Venable name and raised the concern to my father. As The New York Times reports about the incident,

Sensing an opportunity, Mr. Burris told Ms. Birts that he would be pleased if the family would no longer allow the Klansmen to hold rallies on its property at the base of the mountain, where the 60-foot crosses were burned each Labor Day weekend. The deal was struck…that left the Klan all dressed up with nowhere to go![1]

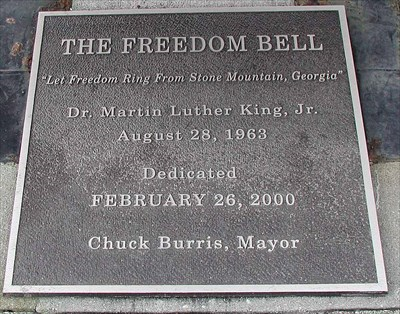

Despite this success and his disdain for the Klan and the vivid memory of the cross burning in his yard when he was only 3 years old, my father never banned the Klan from the city. He served as mayor from 1997–2001. About this, my father used to say, “God does have a sense of humor!” During the interview with The New York Times, he stated, “There’s a new Klan in Stone Mountain, only its spelled with a C: C-L-A-N, Citizens Living As Neighbors. And I guess I’m the Black dragon!” My father was amused at the fact that Dr. King and James Venable shared the same birthday, January 15th and to further cement Dr. King’s legacy in the town and replace hatred with hope, on February 26, 2000, my father placed the “Freedom Bell” in the middle of downtown Main Street to honor Dr. King’s legacy, with an inscription that reads, “Let Freedom Ring from Stone Mountain, Georgia.”

As a city councilman and during his tenure as mayor, my father added new sidewalks in the city, stopped the Klan from marching down Main Street, raised the pay for police officers and firefighters, reduced property tax appraisals on the elderly, cleansed the city of all the crack houses, diversified the funding for the city’s parks, established a recycling program for the city, advocated for the preservation of historic sites, and reformed the city’s image. To commemorate the 30th anniversary of the March on Washington led by Dr. King, my father organized the Freedom Train which ran from downtown Atlanta to City Hall on Main Street in Stone Mountain. He used to say, “Maybe things are getting a little better. If nothing else, hopefully my election will make people know that the city of Stone Mountain is a good town, that everybody is welcome here, that there are no bars to anyone moving here and finding friends and neighbors.” After 6 years serving on the city council, and after receiving wide support from black and white citizens of Stone Mountain, he decided to run for mayor. His message was about equality and economic development through reviving business interests in the city. Although the position of mayor in Stone Mountain was officially a part-time position, he worked full-time as mayor, earning only $300 a month. My father recalled later a phone call he received from a 92-year old white woman who was a lifelong resident of Stone Mountain. She asked him what kind of mayor he was going to be, whether he would be a mayor for black people or white people or for everyone? My father gently but unwaveringly assured her that he was going to be the mayor for everyone! To which she replied, “Well then I guess I don’t mind turning the city over to you black folks as long as y’all are gonna act right!”

My father as mayor established programs to cultivate a sense of community among the residents of Stone Mountain. He converted an old gymnasium into a community movie theater and initiated a program called, “The Mayor’s Saturday Night at the Movies”. Family and community-oriented films were shown to the public for free; popcorn and refreshments were provided complimentary of the Mayor’s Office. My father’s project for adding sidewalks in the city helped encourage families to walk together to the event along with other neighbors, which facilitated people getting to know one another to and from the event. He sought to make the city a pedestrian-friendly town that would connect businesses, neighborhoods, and main street together through the installation of sidewalks across Stone Mountain. My father once said, “I want to see people walking into town to do their shopping, to take their kids for ice cream. When people walk through town, they get to know their neighbors, and this enhances their sense of community.” Recognizing the changing demographics of Stone Mountain along with the dark past of the city, my father used to say,

This area is rich in history. Some of it is painful to many people. I want to deal with those facts in a way that people can profit from. This should be a place where everyone can come to the table, not just black and white residents but also Hispanic and Asian… The place has a tricky history—one of the older developments here was built on a Native American burial ground. We’ve got to take a careful, respectful look at the past, in a way that educates and helps heal old wounds.

My father’s election as the town’s first black mayor made local and national history. He was invited by President Clinton as an honored guest for the State of the Union Address in 1998 and was seated with the first lady. After his mayoral term ended in 2001, my father became executive director of the Southern Regional Council, a non-profit organization established in 1944 in order to create racial equality and avoid racial violence across the southern United States. My father worked to enhance voter registration and political awareness as part of the goals of the organization. In 2007, he left public service for the private sector and relocated to Baltimore, Maryland in order to work at Lockheed Martin as a senior IT manager. During that same year, my father became suddenly ill and was hospitalized and diagnosed with a rare incurable disease called amyloidosis, in which abnormal protein builds in body organs and tissues. He desperately wanted to attend the inauguration of Barack Obama but was too ill to leave his hospital bed. He died from post-surgery complications on Thursday night, February 12, 2009, at age 57. My sisters, Sasha Abdur-Rashid, Khadeejah Abdur-Rashid, and Jameelah Abdur-Rashid are all also his daughters, and my mother, despite remarrying and having two other daughters (Fatima Abou-Harb and Ruyaa Mahmud), never changed her last name back, remaining to this day Jehan Abdur-Rashid.