[1] Sylviane A. Diouf,

Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas (New York: NYU Press, 2013).

[3] Kevin Cokley, Brittany Hall-Clark, and Dana Hicks, “Ethnic Minority-Majority Status and Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Perceived Discrimination,”

Journal of Mental Health Counseling 33, no. 3 (2011): 243–63.

[4] Robert M. Sellers, Mia A. Smith, J. Nicole Shelton, Stephanie A. J. Rowley, and Tabbye M. Chavous, “Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A Reconceptualization of African American Racial Identity,”

Personality and Social Psychology Review 2, no. 1 (1998): 18–39.

[5] For a broad overview of the subject, see Sherman A. Jackson,

Islam and the Blackamerican: Looking Toward the Third Resurrection (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[6] Hazel Markus and Paula Nurius, “Possible Selves,”

American Psychologist 41, no. 9 (1986): 954.

[7] A powerful example of the change in beliefs was when the companions traveled to Egypt and the ruler of Egypt mocked them for being led by ʿUbādah ibn Ṣāmit, a Black companion. They responded to his racist comments saying, “Even though he is black, as you can see, he is the best in status among us. . . . Blackness is not something bad among us.” Details of the encounter can be found here: Omar Suleiman, “When the Sahaba Met a Racist King | Virtual Khutbah,” YouTube, June 5, 2020,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hiWMVOjkoLk.

[8] This subject is beyond the scope of this paper. It has been well-documented that many of the centers of learning in the Islamic empire were led by freed slaves of color. For example, ʿAtāʾ ibn Abī Rabāḥ, a Black scholar, was the intellectual leader of Mecca.

[9] Quoted in William Safire, ed.,

Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1997).

[11] William Edward Burghardt Du Bois,

The Souls of Black Folk (London: Oxford University Press, 2008).

[12] Many scholars since the civil rights era have theorized that oppression is intersectional. Race, class, gender, religion, and other aspects of identity may overlap in discrimination.

[14] Yusuf Nuruddin, “African-American Muslims and the Question of Identity: Between Traditional Islam, African Heritage, and the American Way,” in

Muslims on the Americanization Path, ed. Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad and John L. Esposito (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 215–62.

[15] Sellers et al., “Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity,” 18–39.

[16] Sellers et al., 18–39.

[18] Sheldon Stryker and Peter J. Burke, “The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory,”

Social Psychology Quarterly 63, no. 4 (2000): 284–97; Osman Umarji, “Will My Children Be Muslim? The Development of Religious Identity in Young People,”

Yaqeen, January 16, 2020,

https://yaqeeninstitute.org/osman-umarji/will-my-children-be-muslim-the-development-of-religious-identity-in-young-people/#ftnt12.

[20] Ronald C. Kessler, Kristin D. Mickelson, and David R. Williams, “The Prevalence, Distribution, and Mental Health Correlates of Perceived Discrimination in the United States,”

Journal of Health and Social Behavior 40, no. 3 (1999): 208–30.

[21] Tony N. Brown, David R. Williams, James S. Jackson, Harold W. Neighbors, Myriam Torres, Sherrill L. Sellers, and Kendrick T. Brown, “‘Being Black and Feeling Blue’: The Mental Health Consequences of Racial Discrimination,”

Race and Society 2, no. 2 (2000): 117–31; Kessler, Mickelson, and Williams, “Perceived Discrimination,” 208–30; Racial discrimination was associated with lower levels of psychological functioning as measured by perceived stress, depressive symptomatology, and psychological well-being.

[22] Edna C. Alfaro, Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Melinda A. Gonzales-Backen, Mayra Y. Bámaca, and Katharine H. Zeiders, “Latino Adolescents’ Academic Success: The Role of Discrimination, Academic Motivation, and Gender,”

Journal of Adolescence 32, no. 4 (2009): 941–62.

[23] Sawssan R. Ahmed, Maryam Kia-Keating, and Katherine H. Tsai, “A Structural Model of Racial Discrimination, Acculturative Stress, and Cultural Resources among Arab American Adolescents,”

American Journal of Community Psychology 48, no. 3–4 (2011): 181–92; Bonnie Moradi and Nadia Talal Hasan, “Arab American Persons’ Reported Experiences of Discrimination and Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Personal Control,”

Journal of Counseling Psychology 51, no. 4 (2004): 418.

[24] Jacqueline S. Mattis and Carolyn R. Watson, “Religion and Spirituality,” in

Handbook of African American Psychology, ed. Helen A. Neville, Brendesha M. Tynes, and Shawn O. Utsey (Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2009), 91–102.

[25] Mattis and Watson, 91–102.

[26] Christopher G. Ellison, Jason D. Boardman, David R. Williams, and James S. Jackson, “Religious Involvement, Stress, and Mental Health: Findings from the 1995 Detroit Area Study,”

Social Forces 80, no. 1 (2001): 215–49.

[27] Jeffrey S. Levin and Robert Joseph Taylor, “Panel Analyses of Religious Involvement and Well-Being in African Americans: Contemporaneous vs. Longitudinal Effects,”

Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37, no. 4 (1998): 695–709; Ellison, Boardman, Williams, and Jackson, “Religious Involvement, Stress, and Mental Health,” 215–49; Sung Joon Jang and Byron R. Johnson, “Explaining Religious Effects on Distress among African Americans,”

Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43, no. 2 (2004): 239–60.

[28] Ahmed, Kia-Keating, and Tsai, “Structural Model of Racial Discrimination,” 181–92.

[29] Nyla R. Branscombe, Michael T. Schmitt, and Richard D. Harvey, “Perceiving Pervasive Discrimination among African Americans: Implications for Group Identification and Well-Being,”

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77, no. 1 (1999): 135.

[37] According to legend, John Henry's skill as a steel driver was measured in a race against a steam-powered rock drilling machine. He won the race by working nonstop, only to die in victory with a hammer in hand as his heart gave out from stress; Sherman A James, “John Henryism and the Health of African-Americans,”

Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 18 (1994): 163–82.

[38] Mary O. Odafe, Temilola K. Salami, and Rheeda L. Walker, “Race-Related Stress and Hopelessness in Community-Based African American Adults: Moderating Role of Social Support,”

Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 23, no. 4 (2017): 561.

[39] Albert Bandura, “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change,”

Psychological Review 84, no. 2 (1977): 191.

[42] Michel J. Dugas, Andrea Schwartz, and Kylie Francis, “Brief Report: Intolerance of Uncertainty, Worry, and Depression,”

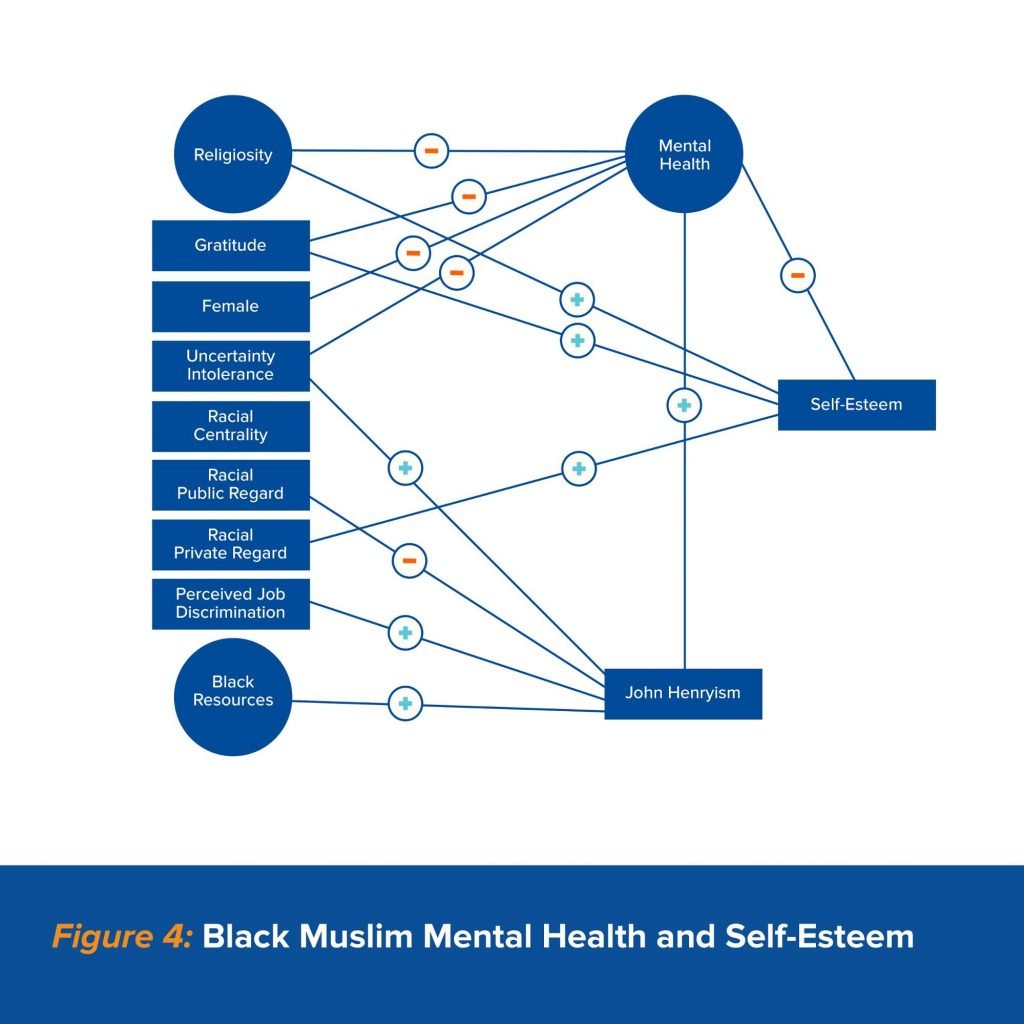

Cognitive Therapy and Research 28, no. 6 (2004): 835–42.

[43] Morris Rosenberg, Carmi Schooler, Carrie Schoenbach, and Florence Rosenberg, “Global Self-Esteem and Specific Self-Esteem: Different Concepts, Different Outcomes,”

American Sociological Review (1995): 141–56.

[44] Stephanie J. Rowley, Robert M. Sellers, Tabbye M. Chavous, and Mia A. Smith, “The Relationship between Racial Identity and Self-Esteem in African American College and High School Students,”

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74, no. 3 (1998): 715.

[45] Monique Bolognini, Bernard Plancherel, Walter Bettschart, and Olivier Halfon, “Self-Esteem and Mental Health in Early Adolescence: Development and Gender Differences,”

Journal of Adolescence 19, no. 3 (1996): 233–45.

[46] Robert M. Sellers, Stephanie A. J. Rowley, Tabbye M. Chavous, J. Nicole Shelton, and Mia A. Smith, “Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A Preliminary Investigation of Reliability and Construct Validity,”

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73, no. 4 (1997): 805.

[47] Kristine Buhr and Michael J. Dugas, “The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale: Psychometric Properties of the English Version,”

Behaviour Research and Therapy 40, no. 8 (2002): 931–45.

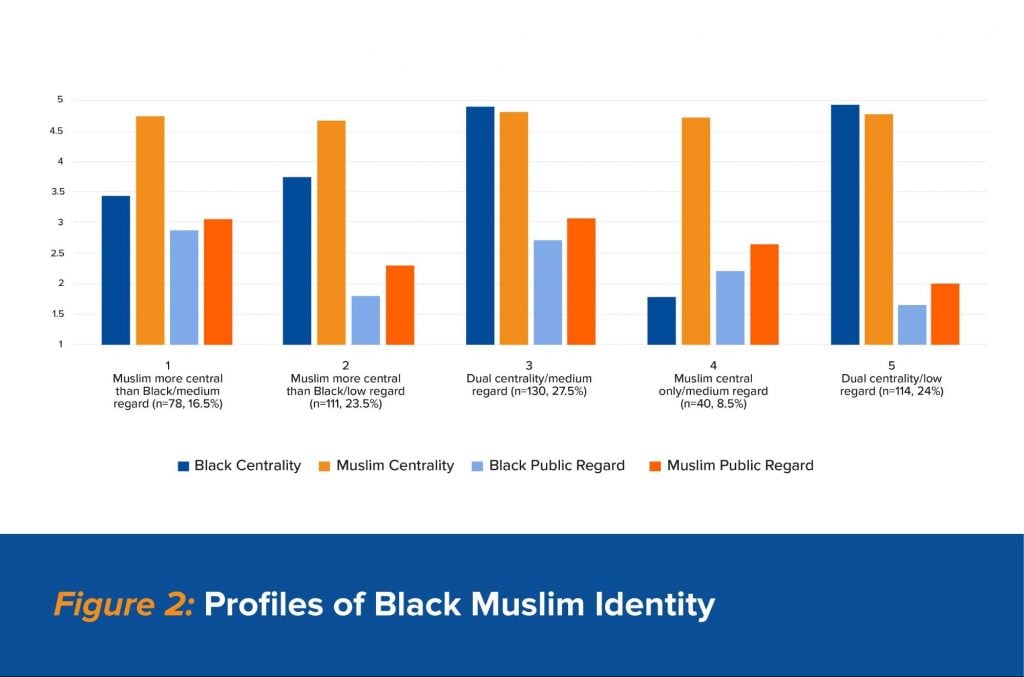

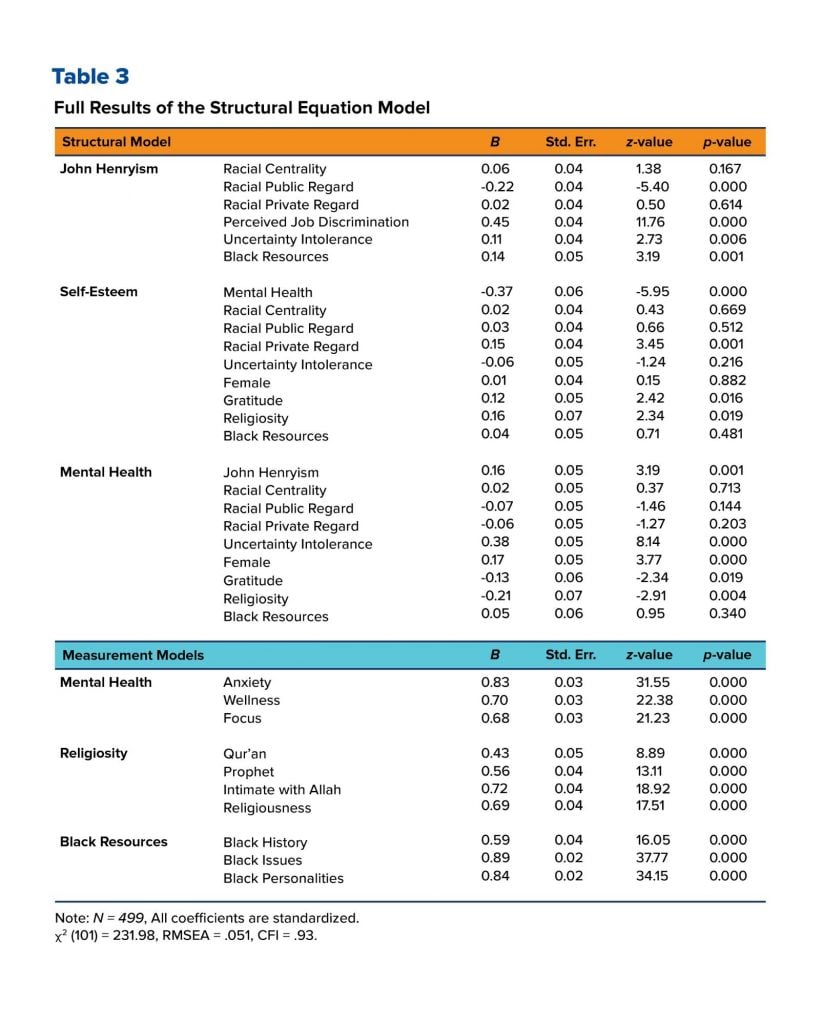

[48] We first ran a hierarchical agglomerative clustering algorithm (Ward’s method) to determine the best cluster solution. K-means clustering was subsequently performed to fine-tune cluster homogeneity by reassigning cases to the optimal cluster.

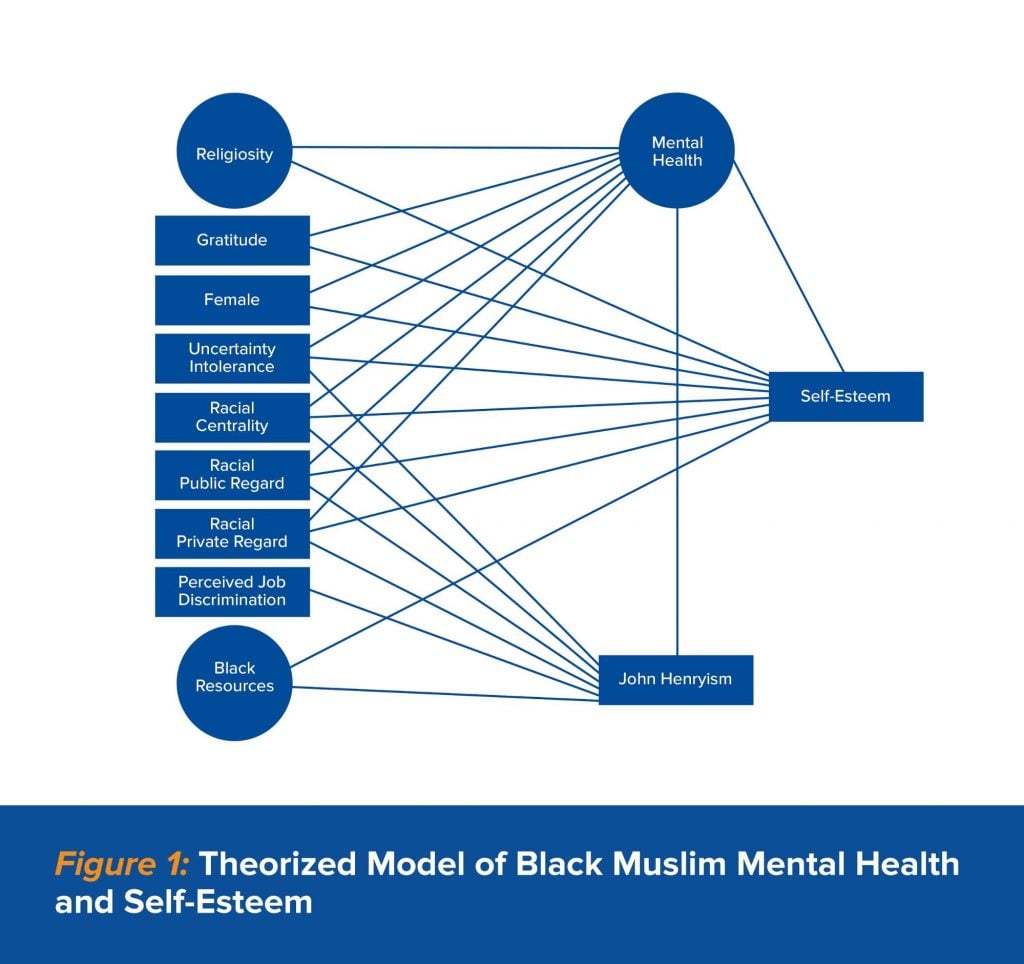

[49] Ovals represent latent variables that have been modeled using factor analysis. Rectangles are observed variables.

[50] The five-cluster solution explained 57% of the variance.

[51] The average perceived job discrimination for the

Muslim central only/medium regard profile was 2.52 compared to 3.39 for all other groups (out of five). This difference of .88 was statistically significant (

t = 4.1,

p < 0.001).

[52] Differences in perceived job discrimination, John Henryism, and self-esteem were statistically significant across the five profiles. T-tests were used to measure statistically significant differences (p < 0.001). Mental health was not significantly different across profiles.

[53] Stata 15 was used to run the model. The model was estimated using full-information maximum-likelihood estimation (FIML). The model fit the data well. χ

2 (101) = 231.98, RMSEA =.051, CFI =.93.

[54] Standardized betas (

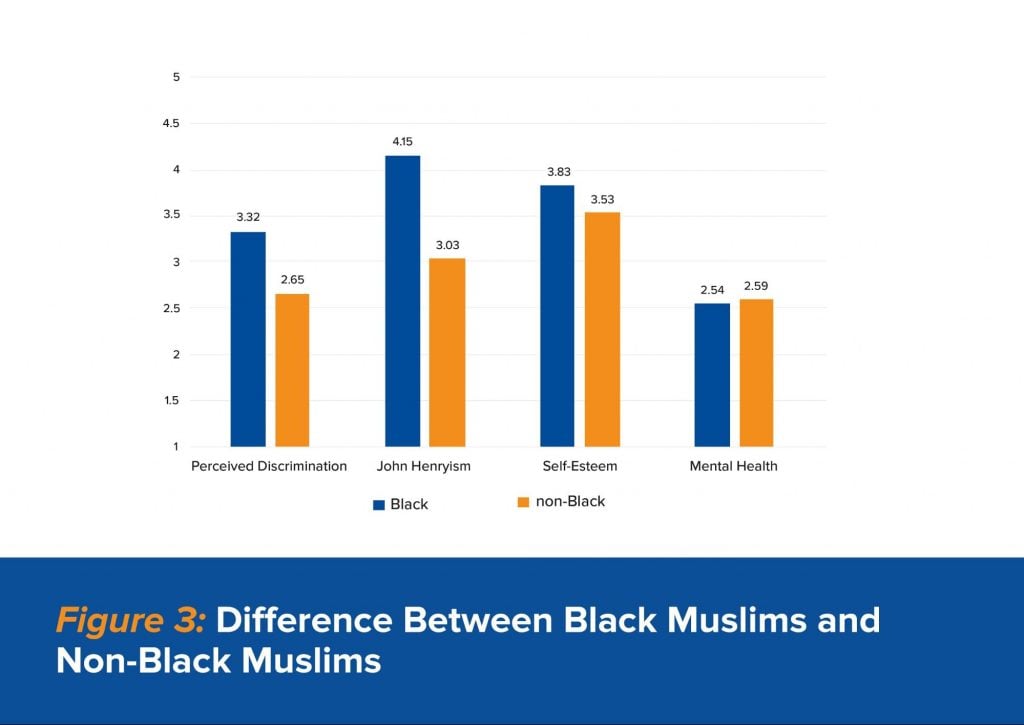

B) are interpreted as follows: a one standard deviation increase in Black centrality was associated with a .12 standard deviation increase in John Henryism, while controlling for all other variables in the model (i.e., holding the value of other variables at the average [mean] level). All significant coefficients meet the threshold of

p < 0.05.

[55] Black public regard had a statistically significant indirect effect on mental health. John Henryism fully mediated its effect on mental health.

[56] Edward Franklin Frazier and C. Eric Lincoln,

The Negro Church in America (New York: Schocken Books, 1974); Benjamin E. Mays, “The American Negro and the Christian Religion,”

Journal of Negro Education (1939): 530–38.

[58] Jacqueline S. Mattis, N'jeri Mitchell, Nyasha A. Grayman, Alix Zapata, Robert Joseph Taylor, Linda M. Chatters, and Harold W. Neighbors, “Uses of Ministerial Support by African Americans: A Focus Group Study,”

American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 77, no. 2 (2007): 249–58; Harold W. Neighbors, James S. Jackson, Phillip J. Bowman, and Gerald Gurin, “Stress, Coping, and Black Mental Health: Preliminary Findings from a National Study,”

Prevention in Human Services 2, no. 3 (1983): 5–29.

[59] We investigated differences in perceptions of job discrimination and John Henryism as a function of age and did not find any differences.

[60] Alex Bierman, “Does Religion Buffer the Effects of Discrimination on Mental Health? Differing Effects by Race,”

Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45, no. 4 (2006): 551–65.

[61] Wizdom Powell Hammond, Kira Hudson Banks, and Jacqueline S. Mattis, “Masculinity Ideology and Forgiveness of Racial Discrimination among African American Men: Direct and Interactive Relationships,”

Sex Roles 55, nos. 9–10 (2006): 679–92.

[62] Bruce Blaine and Jennifer Crocker, “Religiousness, Race, and Psychological Well-Being: Exploring Social Psychological Mediators,”

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21, no. 10 (1995): 1031–41.

[63] Jack L. Daniel and Geneva Smitherman, “How I Got Over: Communication Dynamics in the Black Community,”

Quarterly Journal of Speech 62, no. 1 (1976): 26–39; James H. Cone,

The Spirituals and the Blues (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1991).

[64] Albert J. Raboteau,

Canaan Land: A Religious History of African Americans (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

[65] Carol A. Wong, Jacquelynne S. Eccles, and Arnold Sameroff, “The Influence of Ethnic Discrimination and Ethnic Identification on African American Adolescents’ School and Socioemotional Adjustment,”

Journal of Personality 71, no. 6 (2003): 1197–232; David H. Chae, Karen D. Lincoln, and James S. Jackson, “Discrimination, Attribution, and Racial Group Identification: Implications for Psychological Distress among Black Americans in the National Survey of American Life (2001–2003),”

American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 81, no. 4 (2011): 498.

[66] Rowley et al., “Racial Identity and Self-Esteem,” 715; Camara Phyllis Jones, “Levels of Racism: A Theoretic Framework and a Gardener’s Tale,”

American Journal of Public Health 90, no. 8 (2000): 1212.

[67] Robert M. Sellers and J. Nicole Shelton, “The Role of Racial Identity in Perceived Racial Discrimination,”

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84, no. 5 (2003): 1079.

[68] Lori S. Hoggard, Shawn C. T. Jones, and Robert M. Sellers, “Racial Cues and Racial Identity: Implications for How African Americans Experience and Respond to Racial Discrimination,”

Journal of Black Psychology 43, no. 4 (2017): 409–32.

[69] Hoggard, Jones, and Sellers, 409–32.

[70] Vicki A. Bogan and William Darity Jr., “Culture and Entrepreneurship? African American and Immigrant Self-Employment in the United States,”

Journal of Socio-Economics 37, no. 5 (2008): 1999–2019; John Sibley Butler,

Entrepreneurship and Self-Help among Black Americans: A Reconsideration of Race and Economics (New York: SUNY Press, 2012); William Edward Burghardt Du Bois,

The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study, Series in Political Economy and Public Law, No. 14 (Boston: University of Pennsylvania, 1899).

[71] James, “John Henryism and Health,”

163–82; Umarji and Elwan, “Embracing Uncertainty.”

[72] Asia Bento and Tony N. Brown, “Belief in Systemic Racism and Self-Employment among Working Blacks,”

Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2020, 1–18.

[74] Moritz Kuhn, Moritz Schularick, and Ulrike Steins, “Wealth and Income Inequality in America, 1949–2016,”

Journal of Political Economy, 2019.

[75] The difference in education was 3.9 vs. 4.1 (with 4 representing a bachelor’s degree), whereas wealth was 4.1 vs. 5.1 (with 4 representing an income of $60–79K and 5 representing an income of $80–99K).

[76] Ibram H. Rogers,

The Black Campus Movement: Black Students and the Racial Reconstitution of Higher Education, 1965–1972 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012); James D. Anderson,

The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988); Marybeth Gasman and Roger L. Geiger, “Introduction: Higher Education for African-Americans before the Civil Rights Era, 1900–1964,” in

Higher Education for African Americans Before the Civil Rights Era, 1900–1964 (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2012), 7–22.

[78] William Darity, Darrick Hamilton, Mark Paul, Alan Aja, Anne Price, Antonio Moore, and Caterina Chiopris, “What We Get Wrong about Closing the Racial Wealth Gap,” Samuel Du Bois Cook Center on Social Equity, April 2018,

https://socialequity.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/what-we-get-wrong.pdf.

[79] Krim K. Lacey, Tina Jiwatram-Negron, and Karen Powell Sears, “Help-Seeking Behaviors and Barriers among Black Women Exposed to Severe Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from a Nationally Representative Sample,”

Violence Against Women, June 2020,

https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220917464; Samantha M. Sbrocchi, “Gender Pay Gap: The Time to Speak Up Is Now,”

Touro Law Review 35, no. 2 (2019): 839.

[80] Jamilah A. Karim, “To Be Black, Female, and Muslim: A Candid Conversation about Race in the American Umma,”

Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs,

2006,

225–33.

[81] Ibn al-Jawzī, “Illuminating the Darkness: The Virtues of Blacks and Abyssinians,”

Dār al-Arqam, 2019.

[82] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 5665;

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 2586.

[85] Muhammad, “Black and Muslim.”

[86] Lateef, “Insights for Muslim American Youth Development.”

[88] Martha S. Jones,

Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018); Henry N. Drewy and H. Doermann,

Stand and Prosper: Private Black Colleges and their Students (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011).

[89] Diane J. Chandler, “African American Spirituality: Through Another Lens,”

Journal of Spiritual Formation and Soul Care 10, no. 2 (2017): 159–81.

[90] Martin Luther King Jr.,

Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, vol. 2 (Boston: Beacon Press, 2010); Sherman A. Jackson,

Islam and the Problem of Black Suffering (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[91] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 13;

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 45.