[1] Ibn Qayyim al-Jawzīyah,

Madārij al-sālikīn bayna manāzil īyyāka naʿbudu wa īyyāka nastaʿīn (Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabī, 1973), 3:306.

[2] “

Kalām”

is used

here simply to refer to rational arguments in theological discourse, not necessarily all the doctrines that were traditionally ascribed to it. For a more detailed explanation of the author’s position concerning the place of

kalām in defending the scriptural creed, you may refer to Hatem al-Haj,

Between the God of the Prophets and the God of the Philosophers: Reflections of an Athari on the Divine Attributes (self-pub., 2020).

[3] Besheer Mohamed and Elizabeth Podrebarac Sciupac, “The Share of Americans Who Leave Islam Is Offset by Those Who Become Muslim,” Pew Research Center, January 26, 2018,

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/26/the-share-of-americans-who-leave-islam-is-offset-by-those-who-become-muslim/; Youssef Chouhoud, “What Causes Muslims to Doubt Islam? A Quantitative Analysis,”

Yaqeen, February 13, 2018,

https://yaqeeninstitute.org/youssef-chouhoud/what-causes-muslims-to-doubt-islam-a-quantitative-analysis/.

[4] Musnad Aḥmad, no. 18812, with a

ḥasan (fair) chain of transmission according to the editors. See also comments on the grading in Muḥammad al-Ghazālī,

Fiqh al-Sīrah (Damascus: Dar al-Qalam, 1427 AH), 328.

[5] The abbreviated form without the middle phrase is found in

Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī in

muʿallaq form:

kitāb al-ʿilm,

bāb man khassa bi-al-ʿilm qawman dūna qawm karāhiyyata an lā yafhamū (chapter on one teaching knowledge to some rather than others out of dislike that the latter may not understand it),

https://sunnah.com/bukhari/3/69. Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī رحمه الله mentions the report with the full phrase citing Abū Nuʿaym in

al-Mustakhraj; Ibn Ḥajar,

Fatḥ al-Bārī (Beirut: al-Risalah al-ʿAlamiyyah, 2013), 1:471.

[6] As explained in the commentary, see Abū al-ʿAbbās al-Qurtubī (d. 656 AH),

al-Mufhim (Beirut: Dār Ibn Kathīr, 1996), 1:118.

[8] al-Shāṭibī,

al-Iʿtiṣām (Dammam: Dār ibn al-Jawzī, 2008), 2:311.

[9] This doesn’t mean that he possessed knowledge that no one else had but that he demonstrated discretion in what he taught to the public. A similar principle is seen in the discretion shown by Abū Hurayrah رضي الله عنه regarding dissemination of knowledge related to tribulations (

Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 120); see ʿAbd al-Munʿim Ṣāliḥ al-ʿIzzī,

Difāʿ ʿan Abī Hurayrah (Beirut: Dār al-Qalam, 1981), 79.

[10] al-Shāṭibī,

al-Muwāfaqāt (Khobar: Dār ibn ʿAffān, 1997), 5:171–72.

[11] Summarized from

Musnad Aḥmad (no. 22265), with an authentic chain according to al-Haythamī and al-Albānī.

[12] This is reported sometimes as a statement of ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb or ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib. Ibn al-Qayyim رحمه الله, for instance, expresses the statement to highlight the need for consideration of differences in time and place in the assessment of who can provide legal verdicts. Ibn al-Qayyim,

Iʿlām al-muwaqqiʿīn (Dammam: Dār ibn al-Jawzī, 1423 AH), 6:139.

[14] Al-ʿIzz ibn ʿAbd al-Salām,

Qawāʿid al-aḥkām fī maṣāliḥ al-anām (Cairo: Maktabat Kulliyyat al-Azharīyah, 1991), 1:98; see also ʿAbd al-Majīd Jumʿah al-Jazāʾirī,

al-Qawāʿid al-fiqhīyah al-mustakhrajah min iʿlam al-muwaqqiʿīn (Riyadh: Dār ibn al-Qayyim, 1421 AH), 333.

[15] Musnad Aḥmad, no. 22588.

[16] Some postmodern philosophies do not even accept the idea that absolute truth exists or is attainable.

[18] Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī, no.

6919. In another narration on this topic, it is mentioned that two men went out for travel when the time of prayer arrived, and they did not have water with them. They performed dry ablution with clean earth and prayed, then they later found water. One of them repeated his ablution and prayer, while the other did not repeat them. They came to the Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, and mentioned that to him. The Prophet ﷺsaid to the one who did not repeat his prayer, “You have followed the Sunnah correctly and you will be rewarded for your prayer,” and the Prophet ﷺ said to the one who repeated his prayer, “You will have a double reward.”

Sunan Abī Dawūd, no. 388.

[19] Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Kharashī,

Ḥāshiyat al-Kharashī ʿalá al-mukhtaṣar Sidi Khalīl wa maʿahu ḥāshiyat al-ʿAdawī (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmīyah, 1997), 4:395.

[20] There may be some exceptions such as the rural versus urban divide with the former tending towards conservatism.

[21] A similar principle is seen in the statement of Imam Sufyān al-Thawrī (d. 161 AH), who said, “Verily,

fiqh according to us is when a trustworthy scholar provides a legitimate concession (

rukhṣah); as for being strict (

tashdīd), then anyone can do that well.” See Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr,

Jāmiʿ bayān al-ʿilm wa faḍlihī (Dammam: Dār Ibn al-Jawzī, 1994) p. 784, no. 1467.

[22] Consider for instance the hadith of Umm Salamah where she asked the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, “O Messenger of Allah, why are we [i.e., women] not mentioned in the Qur’an as the men are?” So Allah revealed verse 33:35, “Verily, Muslim men and Muslim women, believing men and believing women . . . ” Reported in

Sunan al-Kubrā of al-Nasāʾī, no. 11405;

Musnad Aḥmad, no. 26575;

Jāmiʿ at-Tirmidhi, no. 3295 and graded fair by Ibn Ḥajar and authentic by al-Albānī. Many conservative preachers today would have one think that any such line of questioning regarding gender equality is the result of capitulating to Western feminism, but Allah Himself validated her question by revealing verses in response, emphasizing equal rewards for both genders. However, this would not mean challenging an established ruling after the cessation of revelation. Allah revealed in response to her inquiry about the inheritance, “And do not wish for that by which Allah has made some of you exceed others. For men is a share of what they have earned, and for women is a share of what they have earned. And ask Allah of His bounty. Indeed Allah is ever, of all things, Knowing.” Qur’an 4:32.

[23] The Prophet ﷺ stated “I intended to prohibit intercourse with a breastfeeding woman until I considered that the Romans and the Persians do it without any defect being caused to their children thereby.”

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no.

1442a. See also ʿAbd Allāh al-Fawzān,

Minḥat al-ʿallām fī sharḥ Bulūgh al-Marām (Dammam: Dār Ibn al-Jawzī, 1428 AH), 7:361.

[25] Kuwait Ministry of Awqāf and Islamic Affairs,

al-Mawsūʿah al-fiqhīyah (Kuwait: Dar al-Safwah, 1995), 35:129.

[26] In fact, in moral choices, the rationale is often a post hoc construction after a judgment has already been reached. J. Haidt, “The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment,”

Psychological Review 108, no. 4 (2001): 814–34,

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814.

[28] “The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ himself personally freed 63 slaves during his life, his wife Aisha freed 69 slaves, and his companions freed numerous slaves, most notably his companion ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAwf who freed an astounding thirty-thousand.” Nazir Khan, “Divine Duty: Islam and Social Justice,”

Yaqeen, February 4, 2020,

https://yaqeeninstitute.org/nazir-khan/divine-duty-islam-and-social-justice/.

[31] Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī,

Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī: Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl āy al-Qurʾān (Cairo: Dār Ḥajr, 2001), 3:378.

[32] Summarized from a report in Ibn Abī Shaybah (no. 37715), Abū Yaʿlá (no. 1818), ʿAbd ibn Ḥumayd (no. 1121), Ibn Hishām, and al-Ḥākim (no. 3002) and declared authentic by al-Dhahabī. See Ibn Hishām,

al-Sīrah al-nabawīyah (Beirut: DKI, 1990), 1:322–23; al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī,

al-Mustadrak ʿalá al-ṣaḥīḥayn (Beirut: DKI, 2002), 2:278; al-Bayḥaqī,

Dalāʾil al-nubuwwah (Beirut: DKI, 1988), 2:204–6.

[34] For his story, refer to Antony Flew and Roy Abraham Varghese,

There Is a God: How the World’s Most Notorious Atheist Changed His Mind (New York: HarperCollins, 2007).

[35] Two pairs of terms in Kant’s terminology are important to understand in this regard. Knowledge that is known without reliance on the senses is

a priori (before experience), while empirical knowledge based on the senses is

a posteriori (after experience). Knowledge that is true by virtue of its definition is analytic (e.g., triangles have three sides), while knowledge that yields new concepts is synthetic. While traditionally, philosophers before Kant had regarded all

a priori knowledge as analytic and all empirical knowledge as synthetic, Kant argued that some knowledge could be synthetic and

a priori (e.g., mathematics).

[36] Sebastian Gardner,

Routledge Philosophy GuideBook to Kant and the Critique of Pure Reason (Abingdon: Routledge, 1999), 33; Michael Rohlf, “Immanuel Kant,” in

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2020 ed., ed. Edward N. Zalta,

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/kant .

[37] Yirmiyahu Yovel,

Kant's Philosophical Revolution: A Short Guide to the Critique of Pure Reason (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 103. In other words, according to Kant, belief in God and immortality is not knowledge that can be demonstrated by pure reason but something that is psychologically necessary to postulate in order for our moral striving to not be in vain; see Will Dudley and Kristina Engelhard,

Immanuel Kant: Key Concepts (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014), 208. This is a limited conception of what knowledge entails, however; the Qur’an states, “So have knowledge that there is none worthy of worship except Allah” (Qur’an 47:19).

[38] Carl Sharif El-Tobgui,

Ibn Taymiyya on Reason and Revelation: A Study of Darʾ taʿāruḍ al-ʿaql wa-l-naql (Leiden: Brill, 2020), 253; see also 244–45, 271.

[39] El-Tobgui, 230–31, discussing the concept of “internal sensation” (

ḥiss bāṭin).

[40] “When the servant is placed in his grave, his companions retrace their steps, and he hears the noise of their footsteps, two angels come to him and make him sit and say to him: What you have to say about this person (the Prophet)? . . .”

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 2870.

[41] Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī, no. 4854.

[42] “This theory proposes that accidents such as stillness and movement cannot simultaneously subsist in one entity, so they happen in succession, and thus must be originated, not eternal... Bodies (

ajsām) cannot exist without certain accidents (

aʿrāḍ) such as movement and stillness, for instance. If so, and we have established that accidents are temporal not eternal, then all bodies are temporal as well, thus, the world originated at some point. This would then lead us to ask who originated it, and through

sabr and

taqsīm (enumeration and division, or the process of elimination) we can establish that God is the one who created it. To the Mutakallimīn, this was their strongest rational proof regarding the creation of the universe by God.” Hatem Al-Haj,

God of the Prophets, 108. See also Al-Haj, 53 and 115.

[43] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 6171.

[44] The Prophet ﷺ said, “Even if a single man is led on the right path (of Islam) by Allah through you, then that will be better for you than the fine red camels.”

Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 4210.

[45] Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī,

Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī, 3:291.

[46] Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī, no. 2639;

Mustadrak al-Ḥākim, no.

1937 and authenticated by al-Dhahabī.

[48] Also sometimes translated as “anomalous” or “irregular,” the linguistic meaning relates to something being an outlier from the rest of the group. Note that the technical meaning of

shādhdh differs depending on which discipline of Islamic studies one is discussing. Its technical meaning discussed here differs from its technical meaning in hadith sciences or in

qirāʾāt for instance.

[49] Note that some scholars used the term

shādhdh to refer to that which is invalid and contradicts clear texts or consensus, in which case it becomes synonymous with

bāṭil.

[50] See, for example, Ibn Taymiyyah’s characterization of the permission of praying while reclining without a need. Ibrāhīm ibn Muḥammad Ibn Muṣliḥ (d. 1362),

al-Nukat wa-al-fawāʾid al-sanīyah ʿalá mushkil al-muḥarrar li-Majd al-Dīn Ibn Taymīyah, 2 vols. (Riyadh: Maktabat al-Maʿārif, 1983), 1:151.

[51] After reviewing the various definitions, ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Namlah prefers the following definition for a

shādhdh opinion: “A position upheld by a small number of

mujtahid scholars without any acceptable evidence” (

qawl infarada bihi qillat min al-mujtahidīn min ghayri dalīl mu’tabar). See ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Namlah,

al-Ārāʾ al-shādhdhah fī uṣūl al-fiqh (Riyadh: Dār al-Tadmurīyah, 2009), 1:89.

[52] Hatem al-Haj, “Shari’ah in Today’s World.”

[53] al-Safārīnī,

Lawāmiʿ al-anwār al-bahīyah (Beirut: DKI, 2008), 2:250–51.

[54] For an overview see Jon Hoover, “A Muslim Conflict over Universal Salvation,” in

Alternative Salvations: Engaging the Sacred and the Secular, ed. Hannah Bacon, Wendy Dossett, and Steve Knowles (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 160–71.

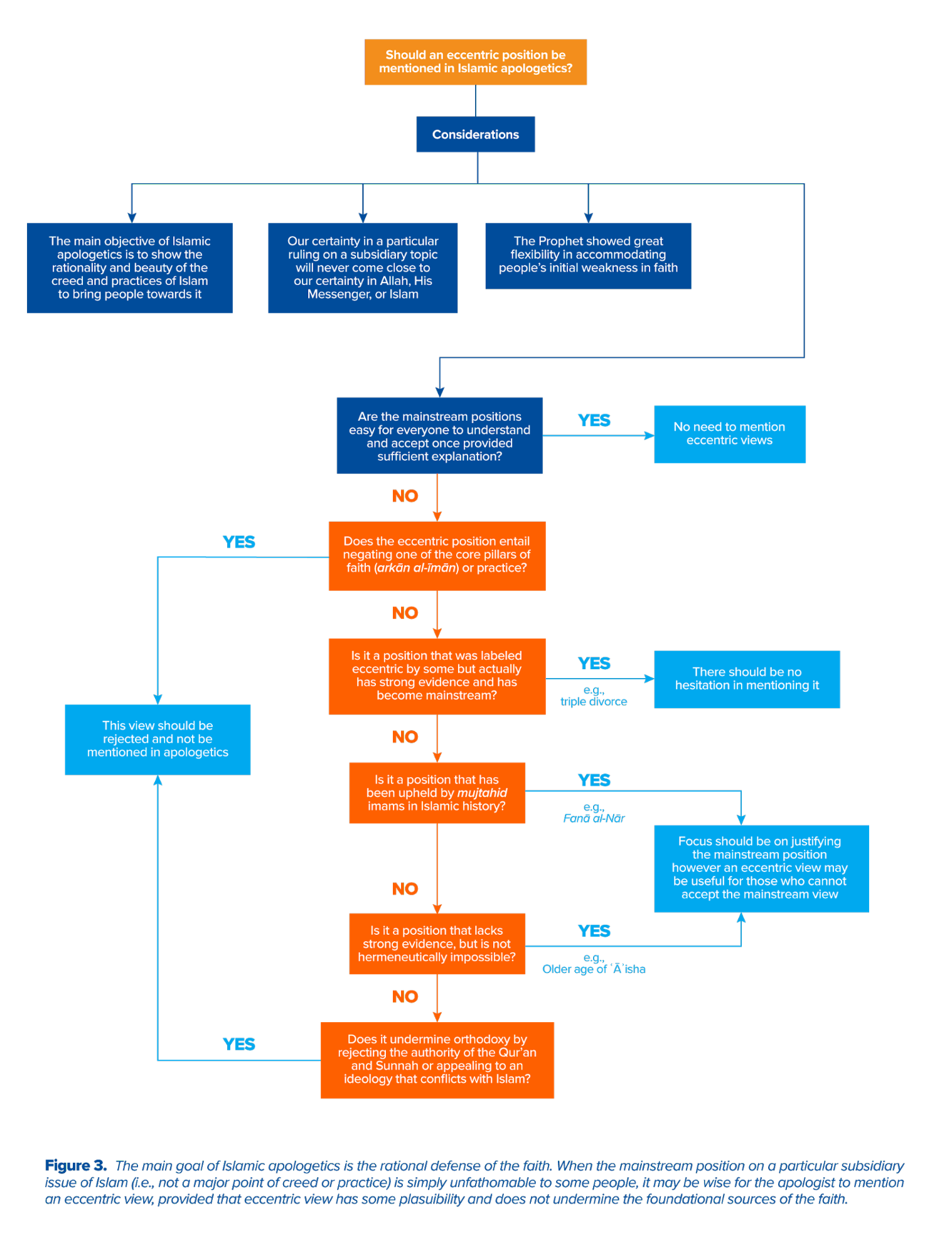

[55] For many people it will be direly needed as they simply cannot wrap their minds around the concept of a benevolent God sentencing people to eternal torment no matter how extensive the rational justifications are, as this requires a degree of faith and trust in Divine Justice that some simply do not yet possess. To appreciate how compelling some of these objections to eternal torment are, one need look no further than the fact that some of these very same objections were persuasive enough for scholars as great as Ibn al-Qayyim to include them in support of eventual vanishing of hellfire.

[57] “Criticism of the ʿĀisha-age ḥadith has been mounted on this basis by the traditionalist Syrian scholar of ḥadith, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Idlibī. He determines the content of the ʿĀisha-age ḥadith to be discrepant (

shādhdh) and defective (

maʿlūl) on the basis of numerous evidences which collectively suggest that ʿĀisha was born four years prior to the start of the Prophetic mission, betrothed to the Prophet ﷺ in the tenth year of prophethood at age fourteen, and married to him one year after the migration at the age of almost 18.” Arnold Yasin Mol, “Aisha (ra): The Case for an Older Age in Sunni Hadith Scholarship,”

Yaqeen, October 3, 2018,

https://yaqeeninstitute.org/arnold-yasin-mol/aisha-ra-the-case-for-an-older-age-in-sunni-hadith-scholarship/.

[59] This is a critically important condition since matters of Islamic theology and Islamic law that are agreed upon cannot be opened for such reevaluation.

[60] For example, Ibn al-Jawzī’s work of

tafsīr entitled

Zād al-masīr is entirely written in this manner. Similarly, this can be seen with many works of comparative

fiqh, as well as commentaries on hadith. For instance Ibn Ḥajar,

Fatḥ al-Bārī, 14:303.

Wa min al-taʾwīl al-baʿīd qawl man qāl al-murād bi-al-qadam qadamu iblīs . . .

wa ẓuhūr buʿd hādhā yughnī ʿan takalluf al-radd ʿalayhi.

[61]“If the hound eats of the game, then you must not eat of it, for I am afraid that the hound caught it for itself.”

Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī, no.

5487.

[62] Sunan Abī Dāwūd, no. 2857, with an authentic chain of narrators according to Ibn Mulaqqin in

Badr al-munīr (Riyadh: Dār al-ʿĀṣimah, 2009), 23:13. The Prophet ﷺ said: “If you have trained dogs, then eat what they catch for you.” Abū Thaʿlabah asked: “Whether it is slaughtered or not?” He replied: “Yes.” He asked: “Does it apply even if it eats any of it?” He replied: “Even if it eats any of it.”

[63] al-Ghazālī,

Iḥyā ʿulūm al-dīn (Beirut: Dār Ibn Ḥazm, 2005), 543.

[64] Ibn Abī Shaybah,

Kitāb al-musannaf fī al-aḥādīth wa-al-āthār, ed. Kamal Yūsuf Hūt (Beirut: Dar al-Taj, 1989), 5:435. Ibn Ḥajar said “Its narrators are reliable.” Ibn Ḥajar,

Talkhīṣ al-ḥabīr (Cairo: Muʾassasat Qurṭubah, 1995), 4:343.

[65] al-Baghawī,

al-Tahdhīb fī fiqh al-Imām al-Shāfiʿī (Beirut: DKI, 1997), 1:51.

[66] al-Mardāwī,

al-Inṣāf fī maʿrifat al-rājiḥ min al-khilāf (Beirut: Dār Iḥyāʾ al-Turāth al-ʿArabī, n.d.), 1:452.

[67] The hadith states, “A man came to the Prophet ﷺ and accepted Islam upon the condition that he only perform two prayers, so the Prophet accepted that from him.” Reported in

Musnad Aḥmad, no. 23079 with a reliable chain according to al-Būṣīrī in

Itḥaf al-khīrah al-maharah (Riyadh: Dār al-Waṭan lil-Nashr, 1999), 1:132. Imam Aḥmad used this narration to establish that a person’s acceptance of Islam is valid even with such unacceptable preconditions, and such a person is later required to fulfill the rulings of Islam. See Ibn Rajab al-Ḥanbalī,

Jāmiʿ al-ʿulūm wa-al-ḥikam (Beirut: Dār Ibn Kathir, 2008), 208; Ibn Rajab al-Ḥanbalī,

Fatḥ al-Bārī sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī (Medina: Maktabat Ghurabāʾ al-Atharīyah, 1996), 4:199–200.

[68] Wahb said: “I asked Jābir about the condition of Thaqīf when they took the oath of allegiance. He said: ‘They stipulated to the Prophet ﷺ that there would be no

sadaqah (i.e.,

zakat) on them nor jihad (striving in the way of Allah).’ He then heard the Prophet ﷺ say: ‘Later on they will give

sadaqah (

zakāt) and will strive in the way of Allah when they embrace Islam.’”

Sunan Abī Dawūd, no. 3025, graded authentic by Ibn al-Wazīr and al-Albānī.

[69] Jāmiʿ at-Tirmidhī, no.

1977. Graded authentic by al-ʿIrāqī and by al-Albānī.

[70] Musnad Aḥmad, no. 8939 and

al-Adab al-Mufrad, no. 273. Graded authentic by al-Zarqānī and al-Albānī in

Ṣaḥīḥ Adab al-Mufrad.

[72] Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr,

Jāmiʿ bayān al-ʿilm wa-faḍlihi, 838.

[74] The Prophet ﷺ said, “He has tasted faith (

īmān) one who is content with Allah as his Lord, with Islam as his religion and with Muhammad ﷺ as his Prophet.”

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 34. See the discussion on the station of spiritual taste (

dhawq) in Ibn Qayyim al-Jawzīyah,

Madārij al-sālikīn, 3:90.

[76] Musnad Aḥmad, no. 7576, and graded fair by Ibn Ḥajar and al-Albānī.

[78] Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 132a,

https://sunnah.com/muslim/1/247. The phrase means that the fact that they regard such matters as grave is an indication of pure faith (

ṣarīḥ al-īmān). al-Nawawī,

al-Minhāj sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim bin Ḥajjāj (Cairo: Muʾassasat Qurṭubah, 1994), 2:205.

[79] Ibn al-Qayyim,

Miftāḥ Dār al-Saʿādah (Mecca: Dār ʿĀlam al-Fawāʾid, 2010), 1:395.

[80] Ibn Taymiyyah,

Majmūʿ al-fatāwá (Medina: Wizārat, 2004), 7:565–66.

[81] Research examining the relation between religious doubts and negative mental health outcomes has found that “religious doubt is associated with depression, general anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, paranoia, hostility, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. To start, religious doubt undermines a potentially important spiritual resource—a cohesive religious worldview via which individuals can interpret and make sense of their daily affairs, as well as major chronic stressors and personal traumas.” Kathleen Galek, Neal Krause, Christopher G. Ellison, Taryn Kudler, and Kevin J. Flannelly, “Religious Doubt and Mental Health Across the Lifespan,”

Journal of Adult Development 14 (2007): 16–25.

[82] The Qur’an also presents the case of a fallacious wager in the story of the man with two gardens. Justifying his ingratitude, the man states that the afterlife is unlikely to come and even if it were to come, God would grant him a better reward (Qur’an 18:36). This is an example of a foolish wager based upon false presumptions as the Qur’an illustrates.

[83] Cited in Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī,

Tafsīr al-Rāzī (Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1981), 17:25, under the eighth argument proving the reality of resurrection, under the commentary of the Qur’anic verse 10:4, “Indeed, He begins the [process of] creation and then repeats it that He may reward those who have believed and done righteous deeds, in justice.” This should be considered a point of reflection for the person to probe further, but can this argument in and of itself provide a basis for belief? After citing this couplet, Ibn al-Qayyim argues that one is to base their faith on certainty and not mere caution, which is the way of the “people of doubt and suspicion.” See Ibn al-Qayyim,

Madārij al-sālikīn, 1:463 under his discussion of the station of holding fast (

al-iʿtiṣām). Evidently, this wager is not what ultimately grounds one’s faith but is useful in considering the consequences of one’s choice.

[84] It has been noted that “many objections to Pascal’s Wager can actually be incorporated into the wagerer’s decision matrix, and thus do not provide reason to refrain from wagering altogether.” Elizabeth Jackson and Andrew Rogers, “Salvaging Pascal’s Wager,”

Philosophia Christi 21, no. 1 (2019): 59–84.

[85] A counterexample to Pascal’s wager proposes that “after they die, splendid things happen to atheists and horrible things happen to theists.” Gregory Mougin and Elliott Sober, “Betting against Pascal’s Wager,”

Noûs 28 (1994): 385.

[86] Lawrence Pasternack, “The Many Gods Objection to Pascal’s Wager,”

Philo 15, no. 2 (2012): 158–78. The author writes,“So long as the classic ‘philosophers’ fictions’ are understood as stipulating something that appears to us to be of trivial value is rather of profound intrinsic value properly suited to being the requirement for what happens to us in our afterlives, we have grounds internal to the Wager for rejecting this category of hypotheses. Such hypotheses imply that we cannot trust an important aspect of our cognitive activity; and without such trust, we cannot consider ourselves fit to engage in wagering.”

[87] James Franklin, “Pascal’s Wager and the Origins of Decision Theory: Decision-Making by Real Decision-Makers,” in

Pascal's Wager, ed. Paul Bartha and Lawrence Pasternack (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 27–44.

[88] In Islam, we are also told that one may receive guidance right before the departure of their soul. The Prophet ﷺ said, “So a man may do deeds characteristic of the people of the (Hell) Fire, so much so that there is only the distance of a cubit between him and it, and then what has been written overtakes him, so he starts doing deeds characteristic of the people of Paradise and enters Paradise. Similarly, a person may do deeds characteristic of the people of Paradise, so much so that there is only the distance of a cubit between him and it, and then what has been written overtakes him, and he starts doing deeds of the people of the Fire and enters the Fire.”

Ṣaḥiḥ Bukhārī, no.

3332.

[89] Bryan Walsh, “Does Spirituality Make You Happy?,”

Time, June 10, 2016,

https://time.com/collection/guide-to-happiness/4856978/spirituality-religion-happiness/. See also “Religion’s Relationship to Happiness, Civic Engagement and Health Around the World,” Pew Research Center, January 31, 2019,

https://www.pewforum.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2019/01/Wellbeing-report-1-25-19-FULL-REPORT-FOR-WEB.pdf.

[90] Arthur Schopenhaur, “On the Sufferings of the Word,” in

Life, Death, & Meaning: Key Philosophical Readings on the Big Questions, ed. David Benatar (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2010), 433.

[91] Ibn al-Qayyim,

Wābil al-ṣayyib, ed. Bakr Abū Zayd (Mecca: Dār ʿĀlam al-Fawāʾid, 1425 AH), 108–9.