The Structure of Scientific Productivity in Islamic Civilization: Orientalists’ Fables

Abstract

Introduction

Aside from the rather curious claim that Al-Ghazālī was an Arab (he was Persian), Hoodbhoy doesn’t explain how one man was capable of destroying an entire civilization – much less how said man’s supposed aversion to free will and mathematics had anything do with 9/11 – but it’s clear that he believes this illustrious scholar responsible for embedding a debilitating and everlasting irrationality into the Muslim world which has resulted in extremism, terrorism, political turmoil, and a lack of Nobel Prizes.But in the 12th century, Muslim orthodoxy reawakened, spearheaded by the Arab cleric Imam Al-Ghazālī. Al-Ghazālī championed revelation over reason, predestination over free will. He damned mathematics as being against Islam, an intoxicant of the mind that weakened faith…Caught in the viselike grip of orthodoxy, Islam choked. No longer would Muslim, Christian and Jewish scholars gather and work together in the royal courts. It was the end of tolerance, intellect and science in the Muslim world.[1]

Defining Terms

Science is not an entity that is obvious to everyone…To begin with, there are disagreements on terminological usage itself, whether the domain of knowledge to which the term ‘science’ is applied is to be confined to the natural sciences, or to be extended to cover the humanities and social sciences as well. Some people use the word in both senses.[4]

The implications of such a view may seem counterintuitive; contrary to being “objective,” facts are entirely dependent on the theories scientists construct in order to coherently comprehend their experiences of the external world. Indeed, the concept of ‘paradigm’ has become integral to understanding the nature of science today within academic circles and provides a foundation from which to ascertain the motivations, scope, and research interests of a scientific community. In explaining the reasoning behind the concept, the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn (d. 1996) – who coined the term in his magnum opus, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions[11] – explains that while human experiences are indeed universal, our understanding of those experiences varies in accordance with our background beliefs:It can be argued that the ideological and political factors are external to science. That within science, the scientific method ensures neutrality and objectivity by following a strict logic – observation, experimentation, deduction and value-free conclusion. But scientists do not make observations in isolation. All observations take place within a well-defined theory. The observations, and the data collection that goes with them, are designed either to refute a theory or provide support for it. And theories themselves are not plucked out of the air. Theories exist within paradigms – that is, a set of beliefs and dogmas.[10]

If two people stand at the same place and gaze in the same direction, we must…conclude that they receive closely similar stimuli. (If both could put their eyes at the same place, the stimuli would be identical.) But people do not see stimuli; our knowledge of them is highly theoretical and abstract. Instead they have sensations, and we are under no compulsion to suppose that the sensations of our two viewers are the same. (Sceptics might remember that color blindness was nowhere noticed until John Dalton's description of it in 1794.)[12]

The ‘Classical Narrative’ and Scholarly Dissent

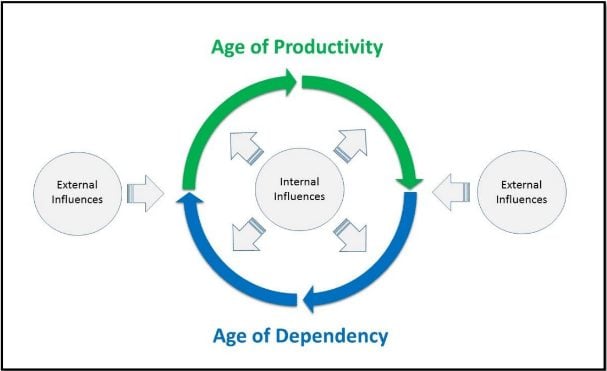

Despite this, Muslims would eventually be unable to sustain their dominance and begin to resort to dependency on foreign ideas and inventions in order to compete with their neighbors. As a result, the balance of power would again shift and Muslims would no longer possess the autonomy and dominance they once had. This is no better evidenced than in the status of Islamic civilization in the contemporary period, which struggles to survive in the face of disunity and the onslaught of Western militarization and its monopolization of the global economy and technology.The historical significance of the Arab conquests can hardly be overestimated. Egypt and the Fertile Crescent were reunited with Persia and India politically, administratively, and most important, economically, for the first time since Alexander the Great...The great economic and cultural divide that separated the civilized world for a thousand years prior to the rise of Islam, the frontier between the East and the West formed by the two great rivers that created antagonistic powers on either side, ceased to exist. This allowed for the free flow of raw materials and manufactured goods, agricultural products and luxury items, people and services, techniques and skills, and ideas, methods, and modes of thought.[20]

The narrative seems to start with the assumption that Islamic civilization was a desert civilization, far removed from urban life, that had little chance to develop on its own any science that could be of interest to other cultures. This civilization began to develop scientific thought only when it came into contact with other more ancient civilizations, which are assumed to have been more advanced…These surrounding civilizations are usually endowed with considerable antiquity, with high degrees of scientific production (at least at some time in their history), and with a degree of intellectual vitality that could not have existed in the Islamic desert civilization. This same narrative never fails to recount an enterprise that was indeed carried out during Islamic times: the active appropriation of the sciences of those civilizations through the wilful process of translation. And this translation movement is said to have encompassed nearly all the scientific and philosophical texts that those ancient civilizations had ever produced.….

In this context, very few authors would go beyond the characterization of this Islamic golden age as anything more than a re-enactment of the glories of Ancient Greece…Some would at times venture to say that Islamic scientific production did indeed add to the accumulated body of Greek science a few features, but this addition is usually not depicted as anything the Greeks could not have done on their own had they been given enough time.….

The classical narrative, however persists in imagining that the Islamic science that was spurred by these extensive translations was short-lived as an enterprise because it soon came into conflict with the more traditional forces within Islamic society, usually designated as religious orthodoxies of one type or another. The anti-scientific attacks that those very orthodoxies generated are supposed to have culminated in the famous work of the eleventh-twelfth-century theologian Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī. [22]

Huff reflects an overt bias against the theological thought and institutions of Islamic civilization, going so far as to use the phrase “Arabic sciences” so as to focus on the linguistic/ethnic characteristics of the translation movement over any perceived influences of religion. According to this view, the only positive contribution by Muslims during this period was the unification of society through a shared language and the appropriation of Greek philosophy – the hard-earned efforts of which would later be paradoxically dismantled by an anti-scientific spirit inherent to Islām itself. However, this raises the question as to how such a movement would have been possible if anti-scientific sentiments existed prior to and during its initiation. In other words, if ‘foreign sciences’ were already unwelcome due to their contrary nature to Islamic doctrine, then it is difficult to ascertain how they were tolerated to begin with and over such a long period of time.If in the long run scientific thought and intellectual creativity in general are to keep themselves alive and advance into new domains of conquest and creativity, multiple spheres of freedom – what we may call neutral zones – must exist within which large groups of people can pursue genius free from the censure of political and religious authorities. In addition, certain metaphysical and philosophical assumptions must accompany this freedom. Insofar as science is concerned, individuals must be conceived to be endowed with reason, the world must be thought to be a rational and consistent whole, and various levels of universal representation, participation, and discourse must be available. It is precisely here that one finds the great weaknesses of Arabic-Islamic civilization as an incubator of modern science.[25]

However, it is unsurprising that scholars supportive of the Classical Narrative would be selective in their reading of these accounts – preferring to mold them in accordance with their preconceived biases rather than attempt a critical examination. As noted previously by Saliba, the projection of the Western experience with religious dogma and institutions has largely served as the backdrop through which other historical events and cultures have been interpreted. As a consequence, Orientalists have actively searched out only those pieces of evidence which appear to conform to this understanding. In line with this, the account of Al-M’amūn’s dream also serves as a convenient means through which to tie in additional historical data which bolsters the Classical Narrative – as it was during his reign (813-833 C.E.) that one of the greatest theological controversies within Islamic civilization occurred: the rise of the Mu’tazilah.This translation movement provided the knowledge base of the emergent sciences. But while this explains part of the picture, and admittedly one of its most important parts, it does not provide a full explanation of the beginnings. To start with, what are the socio-political conditions and the cultural aptitudes that triggered interests in the translation and science in the first place? Second, what were the cultural conditions and the cultural aptitudes that enabled a significant community of interest to know how to translate complex scientific texts, to develop the technical terminology needed for the transfer of scientific knowledge between two languages, to understand scientific texts once they were translated, and to constructively engage the knowledge derived from them? Seen in this light, translation is not a mechanical process but part of a complex historical process that is not reducible to the transfer of external knowledge; rather, it involves forces intrinsic to the receiving culture – most important, the epistemological conditions internal to Islamic culture at the time of the translations.[35]

Khalid ibn Yazid ibn Mu’awiyah was called the “Wise Man of the Family of Marwan.” He was inherently virtuous, with an interest in and fondness for the sciences. As the Art [alchemy] attracted his attention, he ordered a group of Greek philosophers who were living in a city in Egypt to come to him. Because he was concerned with literary Arabic, he commanded them to translate the books about the Art from the Greek and Coptic languages into Arabic. This was the first translation in Islam from one language into another. ….Then, at the time of al-Hajjaj [Ibn Yusuf] the registers, which were in Persian, were translated into Arabic.

….

The records in Damascus were in Greek…The records were translated during the time of Hishām ‘Abd al-Malik…It has [also] been said that the records were translated during the time of ‘Abd al-Malik [ibn Marwan].[40]

Islām as Values – Science as a Tool

This perception would eventually result in the establishment of a scientific tradition quintessentially Islamic (i.e., motivated by the awareness and practice of Islamic values). But in what way was this new science different from any other? In this regard, the historian of science Jamil Regep – commenting on the practice of astronomy during the medieval period – notes the following two approaches generally adopted by Muslim scientists up until this time:The classical scholars of Islam were concerned that in the pursuit of knowledge the needs of the community should not be lost sight of, that ilm should not create undesirable social effects, that it should not tend to such a level of abstraction that it leads to the estrangement of man from his world and his fellow men, or to confusion rather [than] enlightenment. In this framework science is guided towards a middle path. While it should be socially relevant, the idea of a purely utilitarian science is rejected. Moreover, there is no such thing as science for science’s sake; yet the pursuit of pure knowledge for the perfection of man is encouraged. Science, far from being enjoyed as an end in itself, must be instrumental to the attainment of a higher goal.[44]

Broadly speaking, one can identify two distinct ways in which religious influence manifested itself in medieval Islamic astronomy. First, there was the attempt to give religious value to astronomy…The second general way in which religious influence shows up is in the attempt to make astronomy as metaphysically neutral as possible, in order to ensure that it did not directly challenge Islamic doctrine.[45]

As for the intersection between religion and astronomy, and through it the intersection between science and religion…the new astronomy of hay’a was developed in tandem with the religious requirements of early Islam. In a sense this new astronomy could be defined as religiously guided away from astrology. With the pressure from the anti-astrological quarter, usually religious in nature or allied with religious forces, astronomy had to re-orient itself to become more of a discipline that aimed at a phenomenological description of the behavior of the physical world, and steer away from investigating the influences its spheres exert on the sublunary region as astrology would require.[47]

Qūshjī is clearly sensitive to the Ash’arite [theologians’] position on causality, and he makes the interesting observation that part of their objection to it, at least as regards astronomy, has to do with the astrological contention of a causal link between the positions of the orbs and terrestrial events (especially “unusual circumstances”). To get around such objections, Qūshjī insists that astronomy does not need philosophy, since one could build the entire edifice of orbs necessary for the astronomical enterprise using only geometry, reasonable supposition, appropriate judgments, and provisional hypotheses. These premises allow astronomers [in the words of Qūshjī]: “to conceive {takhayyalū} from among the possible approaches the one by which the circumstances of the planets and their manifold irregularities may be put in order in such a way as to facilitate their determination of the positions and conjunctions of these planets for any time they might wish and so as to conform with perception {ḥiss} and sight {‘iyān}.....

What makes Qūshjī’s position especially fascinating are some of the repercussions it had for his astronomical work. Since he claims to be no longer tied to the principles of Aristotelian physics, he feels free to explore other possibilities, including the Earth’s rotation.[49]

- Tawḥīd (Divine Unity):

- Khilāfah (Trusteeship):

- Ībadah (Worship):

- ‘Ilm (Knowledge):

The office of physical science is to discover those properties and relations of things in virtue of which they are capable of being used as instrumentalities; physical science makes claim to disclose not the inner nature of things but only those connections of things with one another that determine outcomes and hence can be used as means.[53]

Al-Ghazālī: Villain or Scapegoat?

So, if Al-Ghazālī was not opposed to our conventional understanding of science, then what was he arguing against and how was he responsible for bringing about the Age of Dependency? To answer the first question, Al-Ghazālī makes it very clear that his criticisms of the philosophers are in regards to nothing more than their abstract non-empirically verifiable beliefs that run contrary to Islām:Another example [of what I agree with] is their statement: "The solar eclipse means the presence of the lunar orb between the observer and the sun. This occurs when the sun and the moon are both at the two nodes at one degree." This topic is also one into the refutation of which we shall not plunge, since this serves no purpose. Whoever thinks that to engage in a disputation for refuting such a theory is a religious duty harms religion and weakens it. For these matters rest on demonstrations—geometrical and arithmetical—that leave no room for doubt. Thus, when one who studies these demonstrations and ascertains their proofs, deriving thereby information about the time of the two eclipses [and] their extent and duration, is told that this is contrary to religion, [such an individual] will not suspect this [science, but] only religion. The harm inflicted on religion by those who defend it in a way not proper to it is greater than [the harm caused by] those who attack it in the way proper to it. As it has been said: "A rational foe is better than an ignorant friend."[56]

This statement alone should already attract suspicion towards the Classical Narrative’s accusations against Al-Ghazālī. Regarding the second question then, it is claimed by critics that his metaphysical views were what ultimately altered Muslims’ perceptions of rationality and science for the worse. More specifically, their ire is often focused on three positions he adopted in opposition to the Aristotelian philosophers at the time. Those positions are as follows: 1) There is no necessary connection between causes and their effects; 2) The study of mathematics can be detrimental to one’s beliefs; and 3) Knowledge should only be acquired and practiced if it possesses utility (i.e., instrumentalism).When I perceived this vein of folly throbbing within these dimwits, I took it upon myself to write this book in refutation of the ancient philosophers, to show the incoherence of their belief and the contradiction of their word in matters relating to metaphysics; to uncover the dangers of their doctrine and its shortcomings, which in truth ascertainable are objects of laughter for the rational and a lesson for the intelligent—I mean the kinds of diverse beliefs and opinions they particularly hold that set them aside from the populace and the common run of men. [I will do this] relating at the same time their doctrine as it actually is, so as to make it clear to those who embrace unbelief through imitation that all significant thinkers, past and present, agree in believing in God and the last day; that their differences reduce to matters of detail extraneous to those two pivotal points (for the sake of which the prophets, supported by miracles, have been sent); that no one has denied these two [beliefs] other than a remnant of perverse minds who hold lopsided opinions, who are neither noticed nor taken into account in the deliberations of the speculative thinkers, [but who are instead] counted only among the company of evil devils and in the throng of the dim-witted and inexperienced. [I will do this] so that whoever believes that adorning oneself with imitated unbelief shows good judgment and induces awareness of one's quick wit and intelligence would desist from his extravagance, as it will become verified for him that those prominent and leading philosophers he emulates are innocent of the imputation that they deny the religious laws; that [on the contrary] they believe in God and His messengers; but that they have fallen into confusion in certain details beyond these principles, erring in this, straying from the correct path, and leading others astray. We will reveal the kinds of imaginings and vanities in which they have been deceived, showing all this to be unproductive extravagance. God, may He be exalted, is the patron of success in the endeavor to show what we intend to verify.[57]

- Al-Ghazālī and Causality

Fire causes burning, lightning causes thunder, winds cause waves, and gravity causes bodies to fall. Such connections between an effect and its cause form the cornerstone of scientific thinking, both modern and classical. But this notion of causality is one which is specifically rejected by Asharite doctrine, and the most articulate and effective opponent of physical causality was AI-Ghazzali. According to AI-Ghazzali, it is futile to believe that the world runs according to physical laws. God destroys, and then recreates, the world after every instant of time. Hence there cannot be continuity between one moment and the next, and one cannot suppose that a given action will definitely lead to a particular consequence. Conversely, it is false to assign a physical cause to any occurrence. In AI-Ghazzali's theology, God is directly the cause of all physical events and phenomena, and constantly intervenes in the world.[58]

Al-Ghazālī’s rendition of his critics’ ridicule includes a number of absurdities that could be derived from misunderstanding his position: from dramatic changes in perception to fruit spontaneously morphing into a human being. Apparently, given that such possibilities are endless, this makes it infeasible to expect any sort of consistency from the observable world.However, Al-Ghazālī answers his fictional opponents by emphasizing the fact that possibilities are not actualities; just because something could be does not necessitate that it will be. He bolsters his point by stating that there is a habitual nature to things that Allāh has created, allowing for the uninhibited acquisition of knowledge and any potential anomalies that may or may not take place. In other words, regardless if one thinks there is no necessary link between causes and their effects, their perception of those habitual relationships will still remain the same. He goes even further to appeal to Allāh’s Omniscience, suggesting that His Foreknowledge limits the occurrence of every possibility, preventing mankind from anticipating and subsequently being paralyzed by them.[To this] it may be said [by our detractors]: This leads to the commission of repugnant contradictions. For if one denies that the effects follow necessarily from their causes and relates them to the will of their Creator, the will having no specific designated course but [a course that] can vary and change in kind, then let each of us allow the possibility of there being in front of him ferocious beasts, raging fires, high mountains, or enemies ready with their weapons [to kill him], but [also the possibility] that he does not see them because God does not create for him [vision of them]. And if someone leaves a book in the house, let him allow as possible its change on his returning home into a beardless slave boy—intelligent, busy with his tasks—or into an animal; or if he leaves a boy in his house, let him allow the possibility of his changing into a dog; or [again] if he leaves ashes, [let him allow] the possibility of its change into musk; and let him allow the possibility of stone changing into gold and gold into stone…Indeed, if [such a person] looks at a human being he has seen only now and is asked whether such a human is a creature that was born, let him hesitate and let him say that it is not impossible that some fruit in the marketplace has changed into a human—namely, this human—for God has power over every possible thing, and this thing is possible; hence, one must hesitate in [this matter]. This is a mode wide open in scope for [numerous] illustrations, but this much is sufficient.

[Our] answer [to this] is to say: If it is established that the possible is such that there cannot be created for man knowledge of its nonbeing, these impossibilities would necessarily follow. We are not, however, rendered skeptical by the illustrations you have given because God created for us the knowledge that He did not enact these possibilities. We did not claim that these things are necessary. On the contrary, they are possibilities that may or may not occur. But the continuous habit of their occurrence repeatedly, one time after another, fixes unshakably in our minds the belief in their occurrence according to past habit.

….

If, then, God disrupts the habitual [course of nature] by making [the miracle] occur at the time in which disruptions of habitual [events] take place, these cognitions [of the nonoccurrence of such unusual possibilities] slip away from [people's] hearts, and [God] does not create them. There is, therefore, nothing to prevent a thing being possible, within the capabilities of God, [but] that by His prior knowledge He knew that He would not do it at certain times, despite its possibility, and that He creates for us the knowledge that He will not create it at that time. Hence, in [all] this talk [of theirs], there is nothing but sheer vilification.[60]

Here, Descartes is quite clear in saying that atheists are incapable of acquiring “real knowledge” because they don’t believe in God. Although he provides many reasons for this conclusion, we need only focus on how it reveals a profound irony emanating from Hoodbhoy’s nomination of the philosopher as a central figure behind modern science; the idea that atheists are scientifically impotent doesn’t quite coincide with a narrative that suggests the inherent rationality of anti-religious thinking.The fact that an atheist can be ‘clearly aware that the three angles of a triangle are equal to two right angles’ is something I do not dispute. But I maintain that this awareness of his is not true knowledge, since no act of awareness that can be rendered doubtful seems fit to be called knowledge. Now since we are supposed that this individual is an atheist, he cannot be certain that he is not being deceived on matters which seem to him to be very evident…And although this doubt may not occur to him, it can still crop up if someone else raises the point or if he looks into the matter himself. So he will never be free of doubt until he acknowledges that God exists.[63]

A careful examination of this passage showcases a very obvious logical inconsistency that renders Descartes’ entire argumentation suspect: If one requires a belief in God in order to have certainty, how is it possible to believe in God with certainty?During the past few days I have accustomed myself to leading my mind away from the sense; and I have taken careful note of the fact that there is very little about corporeal things that is truly perceived, whereas much more is known about the human mind, and still more about God. The result is that I now have no difficulty in turning my mind away from imaginable things and towards things which are objects of the intellect alone and are totally separate from matter…And when I consider the fact that I have doubts, or that I am a thing that is incomplete and dependent, then there arises in me a clear and distinct idea of a being who is independent and complete, that is, an idea of God. And from the mere fact that there is such an idea within me, or that I who possess this idea exist, I clearly infer that God also exists, and that every single moment of my entire existence depends on him. So clear is this conclusion that I am confident that the human intellect cannot know anything that is more evident or more certain. And now, from this contemplation of the true God, in whom all the treasures of wisdom and the sciences lie hidden, I think I can see a way forward to the knowledge of other things.[64]

- Al-Ghazālī and Mathematics

[Al-Ghazālī states:] “There are two drawbacks which arise from mathematics. The first is that every student of mathematics admires its precision and the clarity of its demonstrations. This leads him to believe in the philosophers and to think that all their sciences resemble this one in clarity and demonstrative power. Further, he has already heard the accounts on everybody's lips of their unbelief, their denial of God's attributes, and their contempt for revealed truth; he becomes an unbeliever merely by accepting them as authorities.”

The argument here is clearly that mathematics is potentially, but not necessarily, dangerous. The danger exists because those who study the subject may become inebriated with the power and beauty of precise reasoning, and so forsake belief in revelation.[66]

Surprisingly, Hoodbhoy doesn’t bother to mention the other half of Al-Ghazālī’s statement and infers an entirely different conclusion from what the scholar was actually conveying. However, even more contrary to Hoodbhoy’s accusations is yet another statement by Al-Ghazālī, in which he explains a second reason that studying mathematics may prove to be problematic:[…he becomes an unbeliever merely by accepting them as authorities], asserting: “If religion were true, this would not have been unknown to these philosophers, given their precision in this science of mathematics.” Thus, when he learns through hearsay of their unbelief and rejection of religion, he concludes that it is right to reject and disavow religion. How many a man have I seen who strayed from the path of truth on this pretext and for no other reason! One may say to such a man: “A person skilled in one field is not necessarily skilled in every field…On the contrary, in each field there are men who have reached in it a certain degree of skill and preeminence, although they may be quite stupid and ignorant about other things. What the ancients had to say about mathematical topics was apodeictic, whereas their views on metaphysical questions were conjectural. But this is known only to an experienced man who has made a thorough study of the matter.” When such an argument is urged against one who has become an unbeliever out of mere conformism, he finds it unacceptable. Rather, caprice’s sway, vain passion, and love of appearing to be clever prompt him to persist in his high opinion of the philosophers with regard to all their sciences. This, then, is a very serious evil, and because of it one should warn off anyone who would embark upon the study of those mathematical sciences. For even though they do not pertain to the domain of religion, yet, since they are among the primary elements of the philosophers’ sciences, the student of mathematics will be insidiously affected by the sinister mischief of the philosophers. Rare, therefore, are those who study mathematics without losing their religion and throwing off the restraint of piety.[71]

In summary, Al-Ghazālī also went on to critique the other extreme of those who reject mathematics altogether. As such, when we go beyond a cursory reading of the texts, we find that his concern for studying mathematics rested not in its inherent opposition to religion or science, but in the philosopher’s monopolization of it solely for the sake of their unsubstantiated metaphysical views. Thus, contrary to Hoodbhoy’s assertions, Al-Ghazālī was not against the study of mathematics per se; rather, he attempted to facilitate it by pointing out its licentious misuse by his intellectual opponents.The second evil likely to follow from the study of the mathematical sciences derives from the case of an ignorant friend of Islam who supposes that our religion must be championed by the rejection of every science ascribed to the philosophers. So he rejects all their sciences, claiming that they display ignorance and folly in them all. He even denies their statements about eclipses of the sun and the moon and asserts that their views are contrary to the revealed Law. When such an assertion reaches the ears of someone who knows those things through apodeictic demonstration, he does not doubt the validity of his proof, but rather believes that Islam is built on ignorance and the denial of apodeictic demonstration. So he becomes all the more enamored of philosophy and envenomed against Islam. Great indeed is the crime against religion committed by anyone who supposes that Islam is to be championed by the denial of these mathematical sciences.[72]

- Al-Ghazālī and Instrumentalism

Here, Hoodbhoy indirectly continues his assault on Al-Ghazālī for his opposition to the Aristotelian philosophers, seemingly unaware that the latter conflated scientific disciplines with their metaphysical doctrines. Despite having already shown that instrumentalism was the driving force behind the rise of scientific productivity in Islamic civilization, this accusation makes little sense. As such, we should examine the basis on which Hoodbhoy is uncritically drawing this conclusion.A second factor which discouraged learning for learning's sake was the increasingly utilitarian character of post Golden Age Islamic society. Utilitarianism - the notion that the only desirable things are those which are useful - was not an obsession of Islamic society in the early days of its intellectual development.[73]

In a chapter of his Muqaddima devoted to a lengthy refutation of philosophy the fourteenth century historian Ibn Khaldūn wrote that, “The problems of physics [he was referring to Aristotelian natural philosophy] are of no importance for us in our religious affairs or our livelihoods. Therefore, we must leave them alone.” He was echoing a sentiment already expressed by Ghazālī three hundred years earlier…There is only one principle that should be consulted whenever one has to decide whether or not a certain branch of learning is worthy of pursuit: it is the all-important consideration that “this world is a sowing ground for the next”; and Ghazālī quotes in this connection the Prophetic Tradition: “May God protect us from useless knowledge.” The final result of all this is an instrumentalist and religiously oriented view of all secular and permitted knowledge…[which would] put a curb on theoretical inquiry.[75]

Islamic scientists inherited an astronomy from the ancients that already had been differentiated to a lesser or greater degree from natural philosophy. Islamic astronomers, though, carried this process much farther along, and it does not seem unreasonable to see this, at least in part, as a response to religious objections directed at Hellenistic physics and metaphysics, on the one hand, and to religious neutrality towards mathematics, on the other.[79]

The arguments concerning the corporeal existentia constitute what they [the philosophers] call the science of physics. The insufficiency lies in the fact that conformity between the results of thinking - which, as they assume, are produced by rational norms and reasoning - and the outside world, is not unequivocal. All the judgments of the mind are general ones, whereas the existentia of the outside world are individual in their substances. Perhaps, there is something in those substances that prevents conformity between the universal (judgments) of the mind and the individual (substances) of the outside world. At any rate, however, whatever (conformity) is attested by sensual perception has its proof in the fact that it is observable. (It does not have its proof) in (logical) arguments. Where, then, is the unequivocal character they find in (their arguments)?[80]

Towards a New Understanding

… a scientific tradition is continuous, as such, it cannot be interrupted. For, if there is an interruption, it may not continue creatively as it is the case with Islamic scientific tradition today. Discontinuity will necessarily turn the members of that tradition to another civilization where they can find a continuous tradition.[83]

What is fascinating about this passage is that it seems to admit of an ideology that intimately connects an ailing Islamic civilization to its now dominant Western counterpart; what the latter was only beginning to experience by the 17th century C.E., was what may have very well determined the destiny of the former by the same period. It is from this passage that I began my journey into discovering how the decline of scientific productivity in Islamic civilization occurred, and it is where, I believe, the answer is to be found.The history of the development of the physical sciences is the story of the enlarging possession by mankind of more efficacious instrumentalities for dealing with the conditions of life and action. But when one neglects the connection of these scientific objects with the affairs of primary experience, the result is a picture of a world of things indifferent to human interests because it is wholly apart from experience. It is more than merely isolated, for it is set in opposition. Hence when it is viewed as fixed and final in itself it is a source of oppression to the heart and paralysis to imagination.

….

Since the seventeenth century this conception of experience as the equivalent of subjective private consciousness set over against nature, which consists wholly of physical objects, has wrought havoc in philosophy.[85]

Notes

[1] Pervez Hoodbhoy, “How Islam Lost Its Way: Yesterday’s Achievements Were Golden,” The Washington Post, December 30, 2001, accessed October 21, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2001/12/30/how-islam-lost-its-way-yesterdays-achievements-were-golden/d325ce2a-146f-4791-b5e7-8e662d991cbb/?utm_term=.08b85096dca1

[2] Stephen Shankland, “Neil DeGrasse Tyson: US need not lose its edge in science,” CNET, June 20, 2014, accessed October 21, 2016, http://www.cnet.com/news/neil-degrasse-tyson-the-us-doesnt-have-to-lose-its-edge-in-science/

[3] This is the formal term used to refer to ‘the West’ (i.e., Europe, the Americas, and their subsequent colonies, territories, etc.).

[4] Osman Bakar, preface to Tawhid and Science, 2nd ed. (Shah Alam: Arah Publications, 2008), xxx-xxxi.

[5] Alparslan Açikgenç, Islamic Scientific Tradition in History (Kuala Lumpur: IKIM, 2014), 12.

[6] Ibid, 13.

[7] Ibid, 45.

[8] Ibid, 15.

[9] “Science,” Oxford Dictionaries, accessed December 6, 2016, http://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/science

[10] Ziauddin Sardar, How Do We Know? Reading Ziauddin Sardar on Islam, Science and Cultural Relations (London: Pluto Press, 2006), 170.

[11] As the reader may easily ascertain, Kuhn’s work was the primary influence behind this paper’s title.

[12] Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 192.

[13] Axiology is the philosophical study of values. Values are generally considered the cherished beliefs of a people that guide them in all their affairs (i.e., morals and ethics).

[14] “Culture,” Oxford Dictionaries, accessed December 6, 2016, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/culture

[15] For a thorough understanding of science in this respect, please refer to Thomas Kuhn’s work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

[16] Alparslan Açikgenç, Islamic Scientific Tradition in History (Kuala Lumpur: IKIM, 2012), 27.

[17] George Saliba, Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2007), 248.

[18] Toby Huff, The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 19.

[19] David Deming, Science and Technology in World History, Volume 2: Early Christianity, the Rise of Islam and the Middle Ages (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2010), 81-82.

[20] Dimitri Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early 'Abbasid Society (2nd-4th/5th-10th c.) (New York: Routledge, 1998), 11.

[21] An Orientalist is broadly defined as “someone who studies the Orient [i.e., the East].” However, it is specifically being used here to refer to those who do so through the lens of a Western bias, viewing other cultures and religions as static, underdeveloped, and inferior.

[22] Saliba, Islamic Science and European Renaissance, 1-2.

[23] Ibid, 234.

[24] Muzaffar Iqbal, The Making of Islamic Science (Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Book Trust, 2009), 73.

[25] Huff, Rise of Early Modern Science, 219.

[26] Sonja Brentjes, “Reviews: Oversimplifying the Islamic Scientific Tradition”, Metascience 13 (2004): 83-86, accessed October 17, 2016, doi: 10.1023/B:MESC.0000023270.62689.51

[27] See, Sonja Brentjes, “On the Location of the Ancient or ‘Rational’ Sciences in Muslim Educational Landscapes (AH 500 – 1100),” Bulletin of the Royal Institute of Inter-Faith Studies 4 (2002): 47-71.

[28] See, Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture.

[29] See, Ahmad Dallal, Islam, Science, and the Challenge of History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

[30] Saliba, Islamic Science and European Renaissance, 13.

[31] Ibid, 28.

[32] Ibid, 40.

[33] Muhammad al-Nadīm, The Fihrist of Al-Nadīm: A Tenth-Century Survey of Muslim Culture, V.2, trans. Bayard Dodge (New York: Columbia University Press, 1970), 583.

[34] Ibid, 579 - 581.

[35] Dallal, Islam, Science, and the Challenge of History, 10-11.

[36] Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic Philosophy from its Origin to its Present: Philosophy in the Land of Prophecy (New York: State University of New York Press, 2006), 121.

[37] Ibid, 122.

[38] Ibid, 124.

[39] Saliba, Islamic Science and European Renaissance, 13-14.

[40] Al-Nadīm, Fihrist, 581-583.

[41] Saliba, Islamic Science and European Renaissance, 50-51.

[42] Ibid, 53.

[43] Ibid, 54-55.

[44] Sardar, How Do You Know?, 137.

[45] F. Jamil Ragep and Alī al-Qūshjī. “Freeing Astronomy from Philosophy: An Aspect of Islamic Influence on Science,” Osiris V. 16, Science in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions (2001), 50.

[46] Saliba, Islamic Science and European Renaissance, 189-190.

[47] Ibid, 186.

[48] Ragep, “Freeing Astronomy”, 61.

[49] Ibid, 61-63.

[50] In fact, it has been argued that Qushjī may have been directly responsible for the later findings of Copernicus. For more on this see, F. Jamil Ragep, “‘Alī Qushjī and Regiomontanus: Eccentric Transformations and Copernican Revolutions,” Journal for the History of Astronomy 36/4 (2005): 359-371.

[51] Sardar, How Do You Know?, 184.

[52] Sardar mistranslated the word for ‘waste’ here as ‘dhiya’. Thus, I have changed it to reflect the correct terminology.

[53] John Dewey, preface to Experience and Nature (London: George Allen & Unwin, LTD., 1929), v.

[54] Michael Liston, “Scientific Realism and Antirealism”, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed January 12, 2017, http://www.iep.utm.edu/sci-real/

[55] Saliba, Islamic Science and the European Renaissance, 247.

[56] Muhammad al-Ghazālī, second introduction to The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 5-6.

[57] Ibid, religious preface, 3.

[58] Pervez Hoodbhoy, Islam and Science: Religious Orthodoxy and the Battle for Rationality (London: Zed Books Ltd., 1991), 105.

[59] Ibid, 120-121.

[60] Ibid, 169-171.

[61] “The tendency to look for evidence in favor of one's controversial hypothesis and not to look for disconfirming evidence, or to pay insufficient attention to it.” – Bradley Dowden, “Fallacies,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed February 21, 2017, http://www.iep.utm.edu/fallacy/#ConfirmationBias

[62] Hoodbhoy, Islam and Science, 11.

[63] René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy with Selections from the Objections and Replies, ed. John Cottingham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 103.

[64] Ibid, 37.

[65] Descartes’ attempt to reconcile his circular reasoning simply amounted to demarcating between immediate knowledge and recollected knowledge:

Lastly, as to the fact that I was not guilty of circularity when I said that the only reason we have for being sure that we clearly and distinctly perceive is true is the fact that God exists, but that we are sure that God exists only because we perceive this clearly: I have already given an adequate explanation of this point in my reply to the Second Objections, where I made a distinction between what we in fact perceive clearly and what we remember having perceived clearly on a previous occasion. To begin with, we are sure that God exists because we attend to the arguments which prove this; but subsequently it is enough for us to remember that we perceived something clearly in order for us to be certain that it is true. This would not be sufficient if we did not know that God exists and is not a deceiver. – Ibid, 106.

In summary, ascertaining the existence of God can be made certain within the moment, but the memory of coming to that conclusion can only be made certain by believing in God. However, the solution is superficial in that it presumes that one’s memory is already reliable enough to recall having ascertained God’s existence with certainty prior to believing in Him.

[66] Hoodbhoy, Islam and Science, 105-106.

[67] Hoodbhoy quotes from W. Montgomery Watt, The Faith and Practice of Al-Ghazzali (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1953), 33.

[68] Al-Ghazālī, Incoherence, 8-9.

[69] Ibid, 10-11.

[70] Ibid, 162.

[71] Al-Ghazālī, Deliverance from Error (al-Munqidh min al-Dalāl), trans. Richard J. Mccarthy, S.J. (Boston: Twayne, 1980), 8-9. Accessed February 14, 2017, https://www.aub.edu.lb/fas/cvsp/Documents/reading_selections/CVSP%20202/Al-ghazali.pdf

[72] Ibid, 9.

[73] Hoodbhoy, Islam and Science, 121.

[74] Abdelhamid Ibrahim Sabra, “The Appropriation and Subsequent Naturalization of Greek Science in Medieval Islam: A Preliminary Statement”, History of Science 25 (1987), 240.

[75] Ibid, 239-240.

[76] Ibid, 239.

[77] Perhaps this should not be surprising given that Sabra did not intend for his thesis to be seen as comprehensive or for Al-Ghazālī to shoulder complete responsibility for the decline. He further claims that it was only “meant as a relevant and possibly illuminating observation that might help in future research by directing our attention in a certain direction rather than others” – Ibid, 240-241.

[78] Ragep, “Freeing Astronomy,” 59-60.

[79] Ibid, 60.

[80] Ibn Khaldūn, The Muqaddimah V.3, trans. Franz Rosenthal (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1967), 251.

[81] Saliba, Islamic Science and European Renaissance, 239.

[82] Ibid, 240.

[83] Açikgenç, Islamic Scientific Tradition in History, 28.

[84] For a more thorough discussion on what Al-Ghazālī considers ‘useful’ and ‘blameworthy,’ refer to Che Zarrina Sa'ari, “Classification of Sciences: A Comparative Study of liJyii' culum aI-din and al-Risiilah al-laduniyyah”, Intellectual Discourse 7(1) (Gombak: IIUM Press, 1999), 53-77.

[85] Dewey, Experience and Nature, 11.